|

|

|

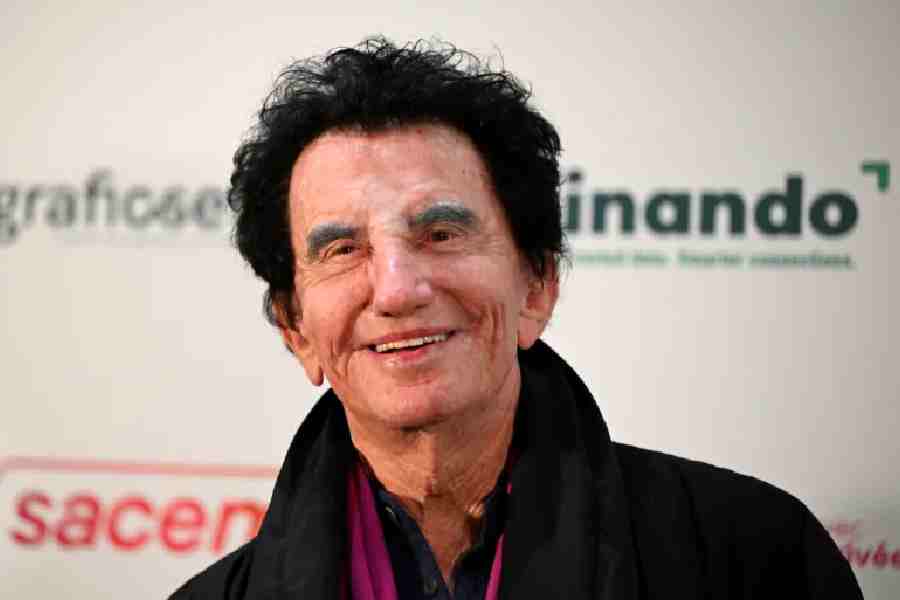

| TECH THAT: (From top) IITians who have joined Iskcon, Bangalore; Swami Pragyapad and Dinesh Ghodke of the Art of Living |

When Dinesh Kashikar joined Bangalore’s Art of Living (AoL) ashram, he mastered the art of fielding queries about his choice of career. “Someone commented that I was intelligent and wondered why I wasn’t earning big bucks in the corporate sector,” recalls the AoL teacher. “I replied, that’s because I am intelligent.”

The barbs keep coming because Kashikar is an unlikely sadhu. The sudarshan kriya (a form of yoga and meditation) instructor studied chemical engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Mumbai, where he was also in the soccer, basketball and wildlife clubs. “But I was looking for something more in life. That’s when I started practising meditation,” he says. After getting his engineering degree and putting in a one-year stint at Hindustan Unilever Limited, Kashikar joined the AoL ashram as a full-time disciple.

Kashikar says his work is no less fulfilling than that of a corporate CEO. “I interact with thousands of students daily and travel the world to give lectures,” says the teacher, who is currently organising AoL’s World Cultural Festival in Germany. “This is much better than writing software programmes,” he adds.

Kashikar has company at the AoL ashram. “There are seven engineers-turned-disciples at the Bangalore ashram. Although we don’t have a policy to attract specific people, their numbers have been increasing,” says AoL spokesperson Swami Pragyapad, himself a graduate of IIT, Mumbai.

God, clearly, seems to be the new recruiter at India’s engineering colleges. An increasing number of students are foregoing corporate careers to join spiritual centres like AoL, the International Society For Krishna Consciousness (Iskcon), the Brahmakumari (BK) Movement and Vipassana.

This year, four IIT graduates joined Iskcon’s Bangalore ashram, taking the number of full-time, engineer disciples at the centre to 40. “Of these, 25 have joined in the last decade,” says Iskcon president Madhu Pandit Dasa, a graduate in civil engineering from IIT, Mumbai. Pandit’s office — with laptops, a conference table and a low-lying seating arrangement — is as swanky as any CEO’s cabin. Only the dress code is different: saffron robes and a shaven head.

The BK Movement — headquartered in Mount Abu, Rajasthan — has nine lakh followers world over, of which two lakh are young people. “Most are students or working professionals,” says B.K. Shivani, a BK teacher who also runs a software and education firm in Delhi. Brahmakumaris believe spirituality should be practised alongside a regular life, and so disciples balance their work life with meditations, study of spiritual scriptures and celibacy.

“Today, by 40, people fulfil their material ambitions. Then they start searching for other things, like spiritual uplift and the meaning of life,” says Shivani.

Also, as urban Indians become spoilt for choice, the novelty of buying a home theatre or going on a holiday is gone. “The idea of buying a fancy car no longer stimulates young people,” explains Shivani. So they start experimenting with other things. “Some try drugs, some try spirituality,” she adds.

Being a full-time spiritualist is becoming popular also because walking this path does not mean setting off for the Himalayas any more. On the contrary, organisations like AoL and Iskcon function like full-fledged companies.

Dinesh Ghodke, head of the world youth programme at AoL, for instance, is a tech-savvy sadhu. “I am active on Twitter and Facebook, as I have to be in touch with my students. I conduct sudarshan kriya courses over Skype for students across the world,” says the graduate of IIT, Mumbai, who had worked for Infosys for two years.

“Spiritual organisations allow devotees to lead regular, urban-based lives,” says Ghodke. Socio-spiritual organisations like AoL — which runs schools for under-privileged children and a de-addiction centre — are a double draw for philanthropic-minded people, he adds.

Iskcon president Madhu Pandit Dasa put his civil engineering education to full use when the temple was built in Bangalore in the 1980s. “Also, running an organisation of this scale requires logistics, accountancy and transparency,” says the IITian president.

Iskcon also allows its disciples to marry and looks after the family financially. “Every requirement of the disciple — from rent to school fees — is met by the ashram. This allows them to practise spirituality while leading regular lives,” says Pandit.

Increasing stress in urban lives is also pushing people to spirituality. Iskcon, for instance, has designed a youth programme. “Students are trained to control the mind, focus, improve concentration and manage stress. In the last eight years, we have trained four lakh students in Bangalore,” says programme co-ordinator Amitananda Dasa, a graduate of the Regional Engineering College, Kurukshetra.

Back in college, Amitananda had his life planned out — engineering, MBA and a corporate job. But a lecture by an Iskcon devotee turned his plan on its head. “The man on the dais, who had been a management student, now wore saffron robes and talked of inner peace. It got me thinking about why he gave up a high-flying life,” recalls Amitananda, who worked for Kirloskar Industries in Bangalore for a year before deciding to give it all up.

The computer science graduate — who now sports saffron robes, a shaven head and carries a BlackBerry — manages the IT infrastructure at Iskcon, besides meditating and attending sadhana sessions. “My personal and professional needs are being fulfilled,” he says.

Spirituality is also becoming a welcome getaway for young professionals who find regular working life mundane. Arvind Lochan Dasa, an IIT, Madras, and University of Missouri graduate, is a case in point. “As a student, I was fascinated with physics and pooh-poohed religion. But when I entered corporate life, I felt I was running too fast and towards no goal,” he says. Lochan became part of Iskcon five years ago. He now heads its Friends of Lord Krishna department and lectures on spiritual quotient.

Lochan believes science and spirituality are not mutually exclusive. “Spirituality is a science of the mind. So a spiritual career attracts students who are interested in intellectual pursuits,” he says.

Monotony made Vilas Vigraha Dasa quit his job as a researcher at Bangalore’s Tejas Networks, and don saffron robes. “My life became a routine of eating, sleeping, earning money and entering into relationships. There was no mental stimulation,” says Vigraha, who graduated from IIT, Guwahati, in 2007 and joined Iskcon last year.

It’s not just the big players of the spiritual sector that are attracting corporate professionals. Lesser known movements — like Soul Searchers and the Delhi-based Conscience of Society — are also drawing attention.

For instance, Srichaitanya chose Soul Searchers to bring a spiritual element to his life. For the last five years, the head of relationship marketing at ad agency McCann Eriksson in Bangalore teaches meditation at Soul Searchers, a two-year-old Delhi-based spiritual movement. “Regular meditation has improved my creativity and productivity,” says Srichaitanya. He adds that over one lakh people practise the Soul Searchers’ meditation methods. Of these, most are either students or working professionals.

Clearly, spirituality is fast becoming a big draw for those who feel the emptiness of a hectic, “successful” modern life.