|

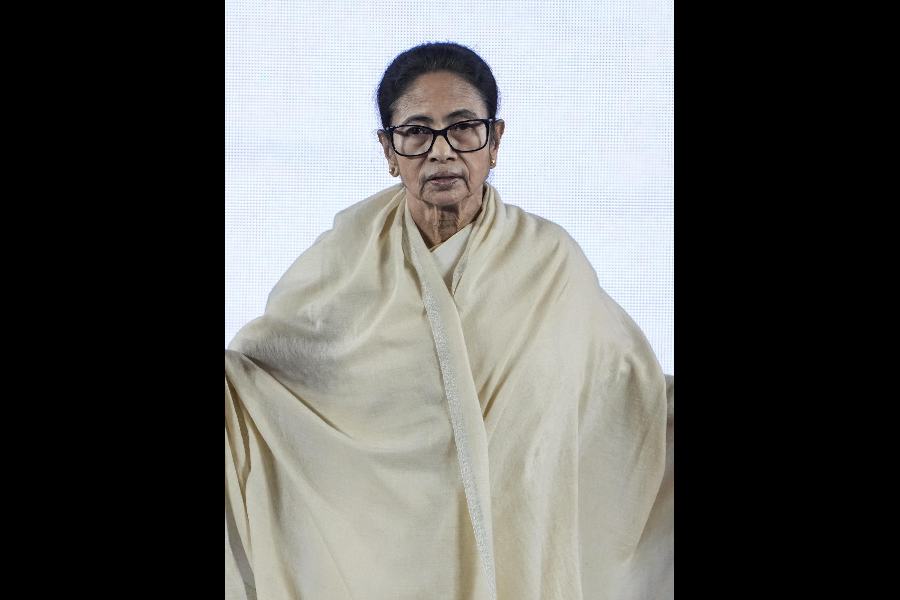

| Illustration: Ashoke Mullick |

A life-size poster of a poor family of five lights up the entrance to Harish Hande’s office. The husband and wife are beaming — and the reason for the couple’s broad smile is there for all to see. A small double tubelight is tied to their hut’s thatched roof. For the first time, the family in Puttur in southern Karnataka has seen electricity in its house.

The poster leaves no doubt about 44-year-old Hande’s mission in life. All that he seeks to do is bring electricity into the lives of the rural poor.

We are sitting in his chamber on the first floor of a two-storey bungalow, which is also the headquarters of his company, Selco-India, in a busy road in JP Nagar, Bangalore. The chamber itself is well-lit with natural light, and I watch the sun’s rays as they dance on the balcony next to it.

Hande was in Manila recently to collect this year’s Magsaysay award, but I notice nothing on that — no framed citation, and certainly no news clippings — in his chamber. But then I don’t see any evidence of his other awards either — the Schwab Foundation for Social Entrepreneurship (Switzerland) prize in 2007 or the Ashden Awards for Sustainable Energy that he won in 2005 and 2007, among many others.

The only time the Magsaysay award crops up in the conversation is when I bring it up. “We would basically like to encourage young social entrepreneurs through the award money. We want passionate youngsters who are ready to take risks and we are ready to fund them,” he says. And he hopes that the award will open a few doors to the often closed rooms where government policies are made.

Hande, as the citation for the $50,000 award says, has been “disproving the myth” that the poor cannot afford the best technology, or maintain and use it productively.

“It is exactly that, a myth. The poor are extremely practical, but they have been seen as beneficiaries, not as partners, which is sad,” he says, running his fingers through his curly hair. He goes on to recount an incident that occurred 18 years ago and left a lasting impression on him.

“I was touring some villages in southern Karnataka when an old lady, probably in her seventies, touched my feet and said that she wanted to see electricity in her house before she died. Remarkably, she also emphasised that she would pay for it. I didn’t know how to react,” he recalls with an incredulous smile.

Since then, Hande and his company have brought light to almost 1,25,000 families, mostly in rural Karnataka. Selco-India, with 170 employees, targets rural families that earn Rs 2,000-3,000 a month and spend Rs 100-150 on kerosene and candles for lighting their homes, and an additional Rs 40 to charge their mobile phones.

“We tell them that they could have solar lighting in their houses for a cost, which they can pay in installments to rural banks,” he says.

Sometimes, though, the cost of installing solar lights in a poor home can be more than the cost of the dwelling itself. But Hande stresses that the poor are ready to pay for electricity as long as they feel it is viable. “But governments don’t get this simple fact,” he says.

Governments, he stresses, are good at conceptualising “big” projects. “They throw big money and hope that it works,” he says with a flip of his hand. “Why should everything be created in Delhi? Is there a single renewable energy ministry official who has been to a village to understand its real needs,” he asks.

Then what is the way forward, I ask. He doesn’t answer the question directly. “My director K.L. Chopra at IIT used to say that if information technology and electronics have to succeed in India, the IT departments have to be closed,” he says with a wink.

I confront him saying that government-bashers like him criticise without seeming to understand the constraints that bind lawmakers. “We don’t criticise them without giving solutions. That’s the difference,” he shoots back.

Hande has been working on solutions for quite a while, possibly even when he was studying for his undergraduate degree in energy engineering at the Indian Institute of Technology in Kharagpur.

But the engineer does not attach much importance to having studied in an IIT — the dream of thousands of students. “I got into an IIT because a lot of people who are intelligent did not sit for the entrance exam. Let us admit that 600 million people in India are not in competition with the other half. Imagine what will happen if you give the other half enough opportunities,” he asks.

But those days, Hande was probably not as vehement. After finishing college, he left India to do his masters degree at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology in the US in the early Nineties.

His world changed after a study trip to the Dominican Republic in the Caribbean where solar energy was used in the houses of the poor. “I always thought big during my research on solar energy, but after that trip, I began re-evaluating myself and decided to work in India at the level where it mattered, even as I pursued my PhD,” he says.

Not that he thinks highly of his “paper degrees” either. “Education makes us more insecure, and it makes us take fewer risks in life,” he says. Hande, however, did take risks.

Once back home, he toured Sri Lanka and India extensively. “What I learnt in the rural areas of these two countries became more important than my masters and PhD — much more important,” he says.

Quite like Swades, I point out, referring to the 2004 film which had a non-resident Indian (Shah Rukh Khan) on a similar mission.

“I don’t fall into the Swades model,” he replies. “I was very clear even before I left for the US that I would be back in India,” he says pointedly. “Films like Swades glorify people who come back from the US, but we don’t glorify the people who have done so much staying in India.”

I realise the subject of non-resident Indians is a prickly one when Hande lets out some more steam. “Why do we glorify them so much when all they do is contribute some money to the IITs or other institutions? Somebody has to tell them, ‘Boss, we need your brains not your cash’,” he says.

His own grey cells went into the formation of Selco-India, which he started with Rs 1,000 taken out of his PhD grant. But he is very clear that his company is not a non government organisation. His business, he asserts, has to be responsible in terms of financial, social and environmental sustainability. “All three are equally important for us. Success is not in terms of high profitability. We are highly successful in social impact but our margins are very low. Higher profits are not our motive,” he says.

But success is not to be scoffed at either. The company had a turnover of around Rs 14.5 crore this year and hopes to cross Rs 16 crore next year.

Understanding rural needs and innovating products is the main job of the “innovations lab” that Hande has set up at Selco. His team has developed solar-fired headlamps for use in midwifery, flower plucking and silkworm rearing in rural areas and also solar-lit sewing machines and other such innovations. “Understanding individual needs is very important for us to succeed in rural areas. That’s what we have been attempting in recent times.”

Hande says he is selective when it comes to choosing people for Selco. “Before appointing someone, we ask ourselves, ‘Is he or she the Selco-type?’ When we like someone, we hire them even when there is no vacancy,” he says.

And what exactly is the Selco-type, I ask. “Passion, that’s what we need for people in this field,” he says punching the air with his fist.

In the last 18 years Hande says that he has “never ever” thought of quitting and taking up something else despite facing several hurdles. “Quitting has never occurred to me. There have been frustrations and plenty of them, but they were not from a personal point of view. I always ask, do we have the time and do we have the solution? That is the motivation. Frustration is also a very big part of motivation,” he says. It is for the first time that I notice the east Indian inflection in his accent when he pronounces the word “occurred” as “ochre-ed”.

Hande explains that he was born in Bangalore, but grew up in Rourkela in Orissa where his father worked with the Steel Authority of India for 40 long years.

Hande himself is a father now — his son was born just after the Magsaysay Award was announced. His software engineer wife lives in Boston in the US with their eight-year-old daughter and the newborn.

“I have been selfish but my family has sacrificed a lot. There was a time when I used to meet my wife once in two years. It’s now once in a few months,” he says with a sheepish smile.

But then, let’s not forget, he has his family with him too — right there at the entrance of his office. And beaming broadly.