-

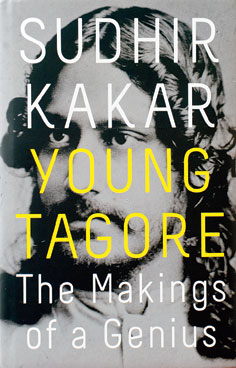

SOULMATE: The book cover; and (above) Kadambari Devi

The main actor for years in the inner theatre of Rabi's adolescence and early youth — playing a crucial role both in the remembered happiness of those years and the consolidation of his identity as a poet and writer — was his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi.

Rabindranath's first memory-picture of Kadambari is that of a 10-year-old girl with 'thin gold bangles on her tender dark wrists' whom he 'circled from afar, afraid to come close'. She had entered the Tagore household as Jyotirindranath's bride, and as far as Rabi was concerned, this sister-in-law, barely two years older than him, had right away disappeared into the fastness of the women's quarters. She now emerged, four years later, to declare the 'advent of a new dispensation' which Rabindranath compares to rainfloods descending from far-off hills, undermining the foundations of ancient dams. Rabi's long pent-up feelings of affection, warmth, love — of Eros in all its multi-hued splendour — gushed out, in song as much as in the subterranean regions of the psyche we blithely call the 'heart' which, in Rabi's case, 'like the breed of grasshopper that blends its hue with the colour of dry leaves', had for so many years worn 'a faded tint, to merge with the dryness' of his days.

Kadambari, a practically illiterate girl for whom books on elementary arithmetic and Bengali had to be purchased when she first became part of the Tagore family, was a remarkable young woman who grew up to be at the centre of Jorasanko's literary activities, and Muse to the boy destined to be the most famous Tagore of all. An incurable romantic, she was yet energetic and bold. Taught horseback riding by a liberal husband, she daily rode out to the Maidan, causing a furore in traditional Bengali society where such a pastime was the province of the British memsahibs and the odd Indian woman who aspired to be a 'brown mem.'...

If Kadambari played the lead, then her husband Jyotirindranath was indispensable as supporting cast in the transformation of a diffident and often unhappy boy into a carefree youngster, increasingly confident of his poetic powers and sanguine about the destiny that awaited him. The pleasure-loving Jyotirindranath, his easy-going ways a complete contrast to those of the grave father, was not only fond of music, dance and theatre but himself spent most of his mornings writing plays or composing catchy tunes on the piano. He encouraged Rabi, who had finally dropped out of his fourth (and last) school after another year of misery, to sit beside him while he played. Rabi's task — if it can be called one for a boy aspiring to be a poet — was to provide the lyrics to the melodies.

In the afternoons, while Jyotirindranath was away in the office for a few hours of desultory work connected with the management of family estates, Rabi would read out loud to Kadambari who preferred to receive the gifts of literature through her ears than her eyes. The readings would be his own poems or writings of Bengali literary icons of the time, such as Bankim Chandra's novel Bishabriksha (The Poison Tree) that was being serialised in a popular journal, Bangadarshan, at the time. The image of those sultry afternoons — the boy declaiming his verse to an intent young woman who is fanning him with a hand-held fan to stir a faint cooling breeze — is one of the most memorable scenes in Satyajit Ray's film Charulata, based on Rabindranath's own fictional representation of those halcyon days. In dedicating his poems — composed between the ages of 13 and 18, and collected in Shoishabsangeet (Childhood Songs) — to Kadambari, Rabindranath says that he wrote them sitting next to her, and all the memories of those affectionate moments are alive in these poems.

Kadambari was not only Rabi's intimate companion in his journey as a budding poet, but also caretaker of his more prosaic, corporeal needs. For a boy like Rabi, who has become resigned to the frugal and tasteless meals dished out by the servants, Kadambari's lovingly cooked dishes that replaced his earlier ruder fare were a gustatory revelation, as much a sign of her love as the serious attention with which she listened to his songs. Ailing and close to death, Rabindranath could still summon the taste of his favourite, mashed chorchori, mixed vegetables prepared with shrimp with a light flavouring of chillies, which Kadambari cooked specially for him.

In the evenings, Rabi joined Jyotirindranath and Kadambari on the terrace that had been transformed by her into a garden with rows of tall palms along the balustrades, surrounded by sweet-smelling flowering shrubs — oleander, tuberose, chameli, champa. At the age of 80, Rabindranath's boyhood memories of those enchanted evenings are as sensual as they are precise.

***

In later life, Rabindranath looked down upon his youthful creations, such as his first published long poem Kobikahani, which he wrote at the age of 16, as effusions of boyhood straining after effects since they were products 'of that age at which a writer has seen practically nothing of the world except an exaggerated image of his own nebulous self.' The earthly muse for those creations, however, merges with its heavenly counterpart as Kadambari acquires an almost transcendent dimension in the old poet's memory. Thus, in the letter to Andrews in which Rabindranath is expressing his homesickness for India, it is Kadambari's visage I espy behind the mask of the Jibandebta when he writes of 'my first great sweetheart — my Muse' and grieves:

'But where is the sweetheart of mine who was almost the only companion of my boyhood and with whom I spent my idle days of youth exploring the mysteries of dreamland? She, my Queen, has died and my world has shut against the door of its inner apartment of beauty which gives on the real taste of freedom.'

Some of Rabindranath's biographers have called Kadambari 'the deepest female influence on Rabindranath's youth', 'playmate and guardian angel', 'deepest heartfelt realisation in [Rabindranath's] life'. But perhaps what she meant to Rabindranath is best expressed in his own words, even when Kadambari is not their explicit addressee: 'The heart of human beings is like liquid, which changes shape if the containers are different. Very rarely it finds the ideal container where it will not feel the emptiness or constriction.' Kadambari was simply Rabi's ideal container.

As Rabi's adolescence gives way to youth, there is a subtle change in the mood of the relationship. The first hint comes in Rabi's memory of accompanying Jyotirindranath and Kadambari to their garden estate, a small two-storeyed house on the banks of the Ganges. It has begun to rain and Rabi has just composed a tune to the poet Vidyapati's verse.

'Enamelled with melody, that cloudy day on the Ganga shore survives, even now, in the jewel casket of my rain songs. I remember the gusts of wind that assailed the treetops every now and then, causing a great stirring and swaying, among the branches, the dinghies scudding along the river, their white sails tilting in the wind, the splash of tall plunging waves upon the ghat. When Bouthakrun returned, I sang the song for her. She listened in silence, without uttering a word of praise. I was 16 or 17 then. We argued about the pettiest of things, but our exchange had lost their sharpness.'

No longer children, the sexual current in their mutual attraction, and the impossibility of its consummation, had begun to breach the wall standing in the way of its conscious awareness.