|

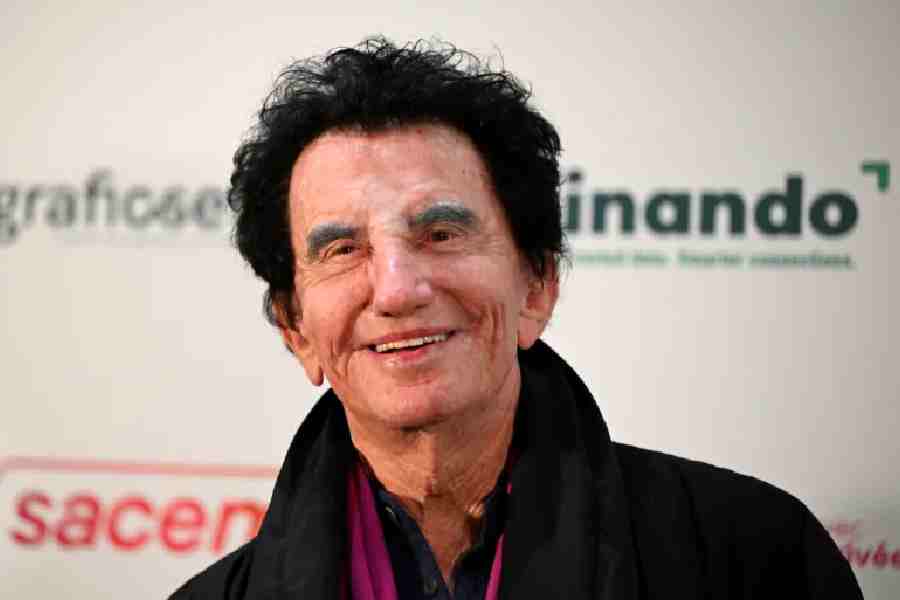

When ghazal maestro Mehdi Hassan passed away early this week in Karachi, a TV channel here asked a fellow singer to talk about him as a person. “We all know about his ghazals and him as a singer, but what was he like as a person?”

Of course, the person thus quizzed made the right noises about Hassan being a great human being, lovely person, etc. Personally, I think it’s best to remember him for his uplifting performances and not try and peep into the green room. For you may not like what you see there.

When Mehdi Hassan was in peak form and was riding the popularity wave in Mumbai’s film industry where everybody toasted and hosted him, he had visited our editorial office near the old Bombay Stock Exchange on Dalal Street. At that time (in the late 1970s, early 1980s) the publishing house I worked for (Eve’s Weekly and Star & Style) was going great guns too, and celebrities from all over would drop in like a must-do on the tourist itinerary.

The arrival of the ghazal king one fine afternoon was special and he was straightaway ushered into the owner’s cabin where J.C. Jain, our head honcho, asked him the usual question every host asks a guest: what would you like to drink? Mehdi squirmed and smiled, didn’t answer. JC pushed and asked, tea, coffee or maybe a soft drink? The singer smiled and countered, what else? JC was puzzled and this went on for a couple of minutes more until the penny dropped. JC sent his driver home to fetch a bottle of Scotch and the ghazal king was appeased.

Coming as he did from a grim land of official prohibition, Mehdi Hassan’s thirst was understandable even on a hot Mumbai afternoon inside a magazine office. The singer made the most of the adulation heaped upon him in Mumbai and Delhi and, in more ways than one, went back home satiated. He flew the Karachi-Mumbai route pretty regularly for a while and had a great time enjoying the hospitality on this side of the border, especially since he could revel in it openly without fearing a backlash (literally) or a cane.

On the other hand, our own home-grown maestro Jagjit Singh had told me, a little before he passed away, that he had gone for a couple of concerts to Pakistan and had encountered the usual problems our singers face there. Unlike the unstinted, open-arm welcome that we extend to every Ghulam Ali or Javed Ali, Pakistan remains a state which does not encourage our artistes to perform freely on its soil. Anyway, Jagjit was smart and came up with the idea that a part of the proceeds from his concerts there would go to help the ailing Mehdi Hassan.

Jagjit had shivered as he narrated the experience of handing over the money earmarked for Mehdi Hassan to his family. According to Jagjit, with Mehdi’s two wives and several children, the hands that had grabbed the money were so grubby-greedy that he came back wondering how much had really gone into settling the mounting hospital bills of Pakistan’s ghazal king.

The stories of Mehdi Hassan’s love for the bottle, his large, unwieldy family, and several years of battling illness and financial woes continued all through the millennium. Ironically, the hale and hearty Jagjit Singh passed away before the long-ailing Mehdi Hassan. Jagjit Singh had a neater, quicker end, even if he too had his share of emotional trauma that settled as heart-tugging pathos in his rich, silken voice. He never really lost the dard in his singing that was enhanced after the early death of his son, Vivek Singh, who died in a car crash. Towards the end of his life, his daughter Monica (from wife Chitra’s first marriage) committed suicide, leaving behind two young kids. All this took its toll on Jagjit Singh who speedily succumbed to a brain haemorrhage.

Truly, the only way to remember Mehdi Hassan or Jagjit Singh is to hear their soulful singing, wonderfully steeped in classical music. There is no need to go backstage and find the off-key notes strewn all over.

Released this week was the sweet Ferrari Ki Sawaari which unfortunately went off on tracks unnecessary to the main story. I don’t know how you feel about it but I sorely missed a swift flesh and blood appearance from Sachin Tendulkar which would’ve rounded off the film really nicely. Wonder what went wrong there, especially because Ferrari producer Vidhu Vinod Chopra and Sachin are such good friends. Their kids go to the same school and Chopra’s son, Agni, is crazy about cricket too. Somewhere I felt disappointed that after such a grand build-up, there was ultimately no Sachin in the film. Felt like an unfinished sawaari.

Bharathi S. Pradhan is editor, The Film Street Journal