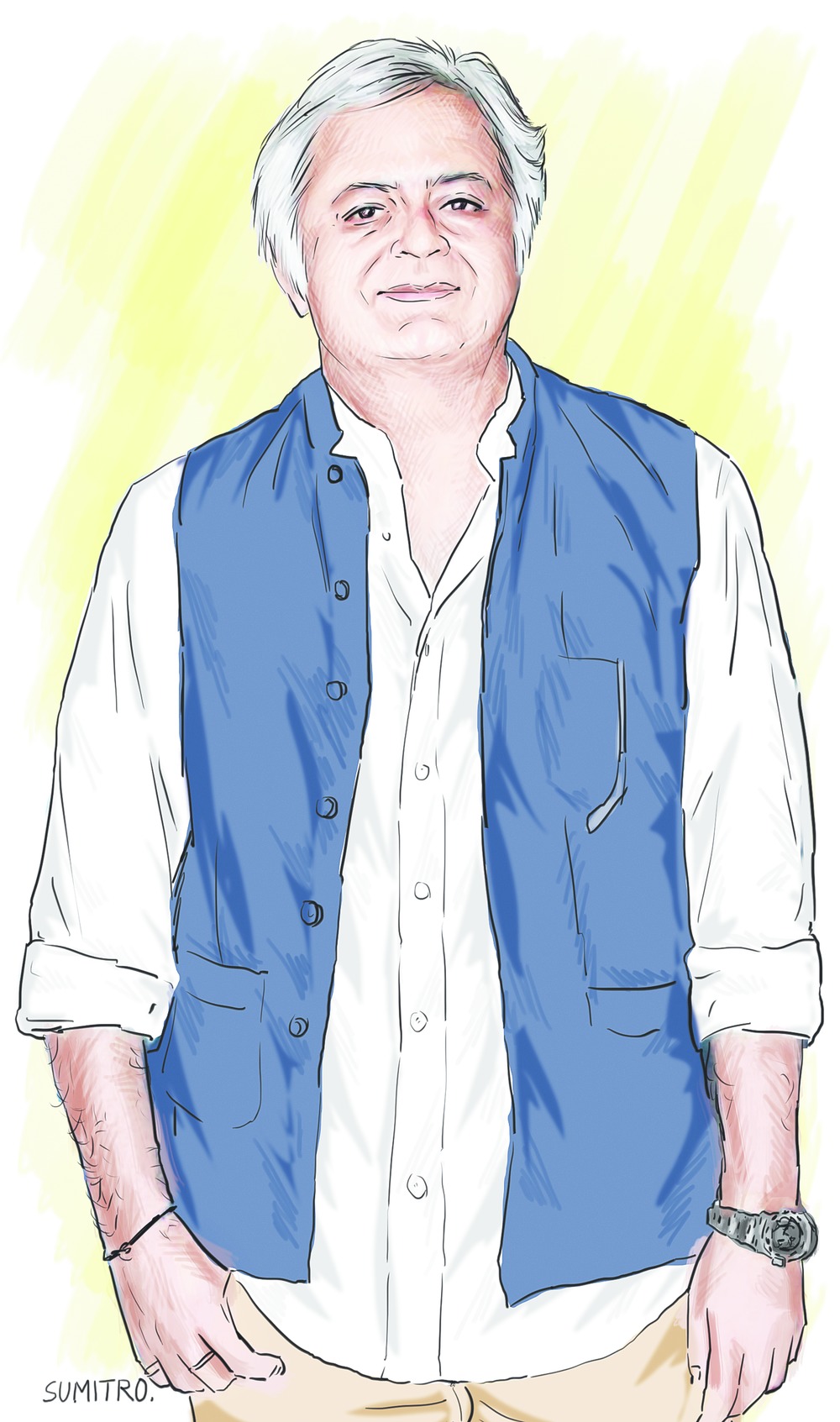

Next to the entrance, a small note says: There are no auditions here. Inside Karma Pictures, in the Andheri axis of Hindi cinema's heartland, it is business-like with a discreet National Award here and a poster there that whisper movies. And in his ripped blue jeans and a sharp white shirt, the silver-haired Hansal Mehta looks more like a trendy corporate house boss than a director whose last three outings - Shahid, CityLights and Aligarh - have been searing.

Mehta, 48, will soon leave for the United States to shoot his next, Simran. The film, about a Gujarati NRI who takes to robbery, reunites the coveted Kangana Ranaut with the stellar Rajkummar Rao, after their triumphant Queen. Mehta will be working with Ranaut for the first time, but Rao is something of a muse for him.

"The boy has immense truth," says Mehta who first met Rao while scouting for Shahid, a 2013 film about Shahid Azmi, the murdered human rights lawyer in Mumbai who got 17 acquittals for Muslims accused of terrorism. The film won National Awards for the director and the actor.

Rao recommended Mehta for CityLights, after the earlier director quit. And Mehta turned to Rao for Aligarh - giving him a choice between the roles of journalist Sebastian and Professor Siras, which was eventually portrayed by Manoj Bajpayee. The 2015 film was based on the true story of a gay teacher in Aligarh, who was "outed" in a sting operation and later found dead.

" Aligarh has been a slow burner but it is resonating with a wider audience," he says, pointing to platforms such as Netflix where the film has been translated in eight foreign languages.

Mehta describes his last three films and Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar (2000) as "chronicles of the times we live in" with a focus on the marginalised. Why so?

"Because I believe I am a marginalised person in the film industry. Still. My personal politics are about the marginalised. My attempt is to ensure they have a better life, through the stories I tell. I don't say I can do it forever, because eventually commerce will catch up. People have stopped visiting theatres to look at people they don't look at even otherwise. And these stories inspire me," he explains.

Mehta's own life can make for quite the biopic. Married by 21, a father at 22, there was hardly any warning that an award-winning filmmaker was incubating. It was in faraway Fiji Islands and Australia in the 90s where he cut his teeth on the tools of the trade.

His employer was in the "duplication" business, making pirated copies of Indian films. Mehta's job was to watch the videos and suggest cuts for small ads. Eventually he started making videos of gurus such as Asaram Bapu and Ram Ozha who had legions of fans among non-resident Indian communities. Then he graduated to wedding videos. Oh yes, he's been there, done that.

Back in India, he started editing television programmes. His editing for a children's song caught Vishal Bharadwaj's attention and they became friends. It eventually led to Mehta's first film ... Jayate, which was never released but, thanks to modern technology and Rajshri films, is online today.

Mehta's conversation occasionally sounds like an awards acceptance speech. He constantly pays his dues - to R.V. Pandit, his first producer, Anurag Kashyap (who was in ...Jayate and would produce Shahid), screenwriter Apurva Asrani (after the interview, he calls back to check if he had mentioned "Apu"), UTV, Disney, Netflix and Amazon... all those who made a difference.

A first film lying in the cans would have felled many a newcomer. But Mehta went on to make more movies, "some good and many bad ones". One that was ahead of its audience was Dil Pe Mat Le Yaar, a tale of migrant workers and lost idealism. Those who took umbrage over a dialogue included Maharashtra Navnirman Sena workers who "blackened" the director's face (the hooliganism was replayed in Shahid).

"Raising money for Dil Pe was a huge struggle. We were three friends who produced it and it actually landed me in a spiral of debt," he recalls. "I was very low. My parents were the only people who were supportive of me. But my marriage was crumbling. My film had not worked. My eldest son was growing up, my younger son had Down's Syndrome. Somewhere I imploded."

Mehta started drinking, "I became a loser for a few months. But, luckily, it continued for just six months, and then I just snapped out of it."He made his next film Chhal, a "funky gangster film". But that sank, too. "So I made a sex comedy - Yeh Kya Ho Gaya. In many ways, I am the father of the genre in India. I actually enjoyed the process but I did not make a very good film. No regrets."

Mehta kept hoping for that one runaway hit that would overnight transform his fortunes. That never happened. Instead, he was "creatively dead, comatose". Films were made, but most of them never got released. "Very fortunately," he smiles.

Then came Woodstock Villa in 2008. "It was like an epiphany. What was this crap? That was the time when I snapped." The day after its release, Mehta packed his bags and left the city.

By then he had met and married Safeena Husain, who runs an education charity. The pair, who have two daughters, retreated to the anonymity and quaintness of rustic Malavali, near Pune, which gradually turned into a weekend getaway for his film buddies. The idea of Shahid was spawned during this retreat. And was promptly dissed by a visiting director glowing with recent Bollywoodian blockbuster success.

"He said Shahid would be a dabba without stars and destined to fail. His remarks worried my parents, and for that I will always hold it against him," Mehta says. More so, he adds, because his mother died before the film's successful theatrical release.

Growing up in Mumbai, films were only "a very small diet". His parents took him along with them when neighbours complained that the young boy would howl when left behind.

"My friends were going to Amar, Akbar, Anthony and I was watching Ankur, Nishant, Manthan, Ardh Satya with my parents," he reminisces. Those films, mainly of rural setting, stayed with him but it was Saaransh which he watched as a senior school student that "blew him away".

Set in Bombay, it was about middle-class families and people he had seen growing up. "It took me into their lives, their turmoil. Into the world of superstition. Growing up in a Gujarati family, we were always exposed to that. This puja, that puja. So they were very relatable. So I said, wow, one can make a film like this also. And it always stayed with me," he says.

For this director of no set genre, death seems to be the hero of his recent films. Mehta nods. "When Apurva was writing Simran, he said thank god, you are doing this. You are not making a film about one more person who is going to die," he says. Instead, he is aiming for fun with this movie after six years of themes that have all but drained him.

"It is a departure and yet it is the same character that I make films about. I have lived abroad also for a long time. I always felt I am on the margins there. At least in Mumbai even if I am on the streets I belong here. It is about somebody's need to belong. It is my migrant story. My migrant story has migrated," he says.

The themes he addresses and his reputation for speaking out must have a price within the industry, one would think. (Last week, he had described censor board chief Pahlaj Nihalani as "out of date" for seeking a series of cuts in the film Udta Punjab.)

"I don't take any pressure any more. I used to, once. The trick to survival in this industry is to not take yourself too seriously." Even so he can be a fierce critic of the government. "That sabbatical made me fearless and I have to speak up when something is wrong."

As he did during the recent spat between Ranaut and Hrithik Roshan, speaking up on behalf of Ranaut, who had accused Roshan of hacking into her private email.

"I spoke out. Not because I am working with Kangana. I would have done that in any case. It is what Aligarh is about - the right to privacy. If Kangana has respected Hrithik's dignity so should he respect hers. All I had to say was that if emails are in the public domain, then it is warped. It was not cool," Mehta says emphatically.

He admits he is bothered by the muck raking by others in the industry. "This entire mockery is now systemic. Character assassination... Before 2014, it was more under the surface. Now it has become brazen," he insists.

Why post-2014, one wonders. "Our true character as a right-wing nation has emerged. And the survival of the right wing thrives on character assassination. You will see that every time somebody who is perceived as weaker or marginalised or as an outsider is attacked, there is character assassination. You will always see that," he retorts.

Even as Simran gets underway, Mehta has quietly wrapped up another film for Karma Pictures. "I cannot talk about it yet. All I can say is it will be the opposite of Shahid," he says cryptically.

Another twist in this man's take.