|

|

|

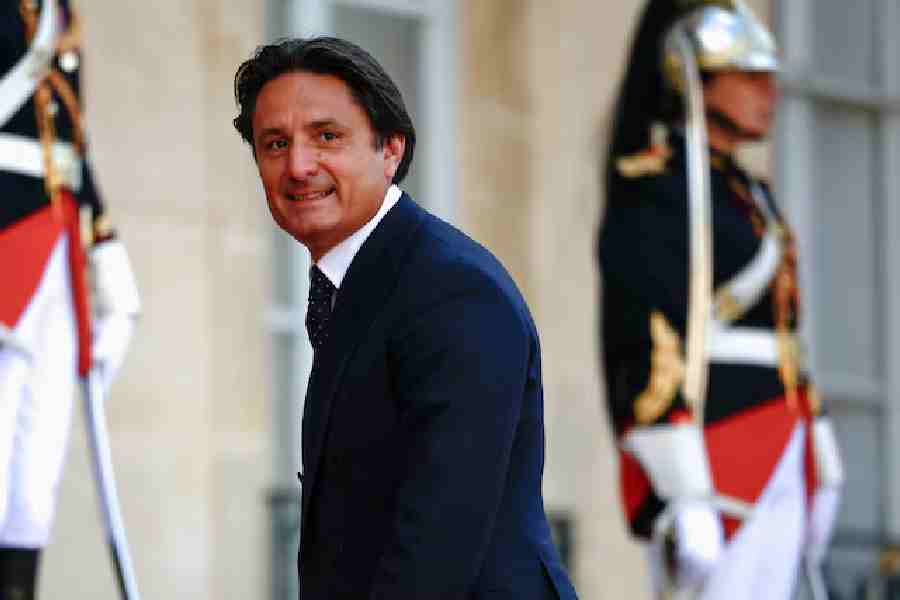

| REMAINS OF THE DAY: (From top) Jawaharlal Nehru flanked by Pamela and Edwina Mountbatten; Nehru in a yogic posture; Mahatma Gandhi with Edwina |

Sunday 11th May (1947)

Yesterday evening Panditji gave us a demonstration of standing on his head, a performance he goes through for about 10 minutes every morning and during which the major problems of India are solved! Actually he really is marvellously fit and had the three of us down on the floor doing the most extraordinary yogi exercises.

I had a long talk with Krishna Menon, about the most cynical person I’ve met so far but very interesting. They are very frank in the way of never agreeing casually for the mistaken sake of manners but catch up at once, something which takes some getting used to. (With hindsight, this is perhaps not surprising if he had been up all night previously with Panditji!) Panditji left.

Special Relationship

My parents had met Pandit Nehru in 1946 when he had travelled to Malaya to meet the Indians living there… Towards the end of the 15 months we spent in India the immediate attraction between my mother and Panditji blossomed into love.

...She became his confidante. Nehru would never write to her until about two in the morning, when he had finished his work, and his letters were a fascinating diary of the creation of India. He would start with a charming opening paragraph, very touching and personal, and he would end affectionately. But the main part of the letters was a diary of everything he had been doing and the people he had seen, his hopes and fears, and, towards the end of his 12-year correspondence, his disappointments and disillusion.

The relationship remained platonic but it was a deep love. And although it was not physical, it was no less binding for that. It would last until death. They met about twice a year. She would include a visit to India in her overseas tours on behalf of the St John Ambulance Brigade and the Save the Children Fund.

…Panditji would come to London for the Commonwealth Prime Ministers’ conferences. He would always come down to Broadlands, our house in Hampshire, for a weekend. We kept a little grey mare for him so that he could come out riding with us.

My mother was on an overseas tour in 1960 and had just left India, carrying out a heavy programme of inspections and engagements in Borneo, when her heart gave out and she died in her sleep aged 58. A packet of letters from Panditji was found by her bedside. In her will she left the whole collection of letters to my father. A suitcase was crammed full of them. My father was almost certain that there would be nothing in the letters to wound him. However, a tiny doubt caused him to ask me to read the letters first. I was happy to be able to reassure him. They were remarkable letters but contained nothing to hurt him.

For me, Pandit Nehru was a very special person. I felt a tremendous warmth towards him from the first time I met him. The whole time we spent in India was no more than 16 months: very short, but it seemed like a lifetime, and if you had asked me whom I loved most after my father and mother, or my sister, undoubtedly it was Panditji. I called him Mamu, which means Uncle. I remember that Panditji frequently used the expression “All manner of things” — he said it to such an extent that we used to tease him about it. My father also felt a real affection for him.

Operation Seduction

Before we had flown out to India, my father had already worked out that if he was to hit the ground running he would need to meet the four most important personalities behind the opposing political ideas. He had already contacted Mahatma Gandhi and Jawaharlal Nehru before he arrived, and he then invited Mr Jinnah and Vallabhbhai Patel. They were about to have a charm offensive unleashed upon them — one of my father’s disarming tools before he would launch in with his pragmatic strategies for movement and solution.

…Growing up in England, we had heard a lot about him (M.K. Gandhi). I’m afraid the ignorant English take on him was “a funny little man in a loincloth”. In fact, he did wear his shawl to come to Viceroy’s House, I think largely because it wasn’t yet that hot although it was the beginning of March, but also my father’s study was air-conditioned and quite cool. After the initial photographs of the three of them outside, as they turned to go in, Gandhi put his hand on my mother’s shoulder, because he was quite frail and quite old. He was so used to his great niece, one of his “crutches”, always being there that he’d always have a hand on one of these girls for support. So instinctively he put his hand for support on my mother’s shoulder. This would have been welcomed by my mother of course, but sadly this photograph caused real outrage in England when it was seen. They thought it was not appropriate at all that this “black hand should be placed on this white shoulder”.

The next day, Gandhi made a great concession to eat his habitual goat curds at Viceroy’s House with the Viceroy. He offered it to my father, who politely tried to refuse and then Gandhiji, with a lovely mischievous smile, insisted. My father said it was the most disgusting green porridge that he’d ever had.

Jawaharlal Nehru

He was a Kashmiri Brahmin but spoke and wrote beautiful English (much better than our own — he was educated at Harrow and Cambridge). He was such a civilised person and such fun, and was the one person that the future of India depended on.

Panditji was seldom aloof with us. But he was definitely a person who went into great silences and one would never have thoughtlessly intruded upon or interrupted him at that moment. One felt that he was wrestling with problems and wanted to be alone. But then, an hour later, he had changed. He would have resolved the problem he was struggling with and he would have that enormous charm again. This was typical of the speed with which his moods could change. He could lose his temper so quickly. I remember one day too many people gave my parents autograph books to sign, the crowd was overbearing, thrusting them in their faces and he became impassioned and took all the autograph books and threw them in the air. My mother was very shocked, but he had a wonderful way of putting his arm around one’s shoulders and giving one a hug and everything seemed fine.

…Another time when I sat next to him at dinner, we talked about my mongoose. Panditji was telling me that when he was in prison the mongooses were always very popular. This led to me saying how dreadful it must have been for him to have been imprisoned for so many years. He acknowledged that it was frustrating not to be able to have access to all the reference books he would have liked… but that the good thing about prison was that it gave one time to think and everyone needs time to think. He added, with a smile, “It would do you good to be in prison for a while.” I was amazed that he showed no bitterness.

Vallabhbhai Patel

I remember a funny incident with this severe man at lunch one day. My mother was forever taking her shoes off under the table because she had quite high heels. And Vallabhbhai had taken his sandals off and we could see that she and he were chuckling. Lots of chuckling was going on and of course he was trying to get her shoes on and she was trying to get his sandals on.

Mohammed Ali Jinnah

Of course the famous story of Jinnah’s first meeting with my parents was about the comment that backfired at their photo-shoot. Jinnah was meticulous and would have prepared a joke — presumably, of course, it was delivered before they were posed: as he had assumed that my mother would be photographed between him and my father, when asked to pose he said, “Ah — a rose between two thorns.” Unfortunately, it was he who was placed in the middle of the composition and not my mother.