The last lap of India's mobile cine-circus as it trundles through remote villages of Maharashtra lighting up the nights. A boy's struggle to escape the impossible darkness of rat-hole coal mines. The feverish adulation of the masses for a southern superstar.

Documentaries are not what they used to be - or were largely thought to be. Neither yawn-inducing, nor preachy, a flood of new documentaries is making waves in the country - and abroad.

Once confined to film festival circuits, they are now everywhere - in commercial cinema halls, on television, in pubs and on video-on-demand (VOD) channels such as Netflix and Amazon.

Shirley Abraham and Amit Madhesia's film The Cinema Travellers won the Special Jury Award at Cannes this year and got rave reviews for its "elegiac" content and stunning visuals. The two directors spent eight years touring, researching and gathering funds for the film, a salute to the keepers of the fading travelling tent cinema culture.

Last year, Chandrasekhar Reddy's Fireflies in the Abyss, a documentary on people working in the coal mines in the Jaintia Hills of northeast India, was premiered at the Busan International Film Festival in South Korea. It had its India launch on July 1, 2016, when it was released in 11 theatre screens in five cities.

From the looks of it, having had a taste of indie films and some true-to-life cinema, audiences in India are willing to loosen the purse strings to watch documentaries on the big screen. In recent times, Indian documentaries such as The Rat Race (on rat killers in Mumbai), Katiyabaaz (on a modern-day Robin Hood who steals electricity to light up poor homes in Kanpur), Gulabi Gang (on fiery women activists of Bundelkhand) and Awake: The Life of Yogananda (on Paramahansa Yogananda) have had theatrical releases. It is another matter that they get obscure slots or are ousted by the feature film of the week. Fireflies in the Abyss may stay in the theatres for just five days before the mega Eid release, Salman Khan's Sultan, stomps it out.

Reddy is not complaining. "A theatrical release has marquee value. It is a viable slot if the film shows for just one week, because I can create that space for a documentary," he says.

India has always had good documentary filmmakers, but previously, their films were mostly screened at festivals. Now, new spaces are opening up. TV channel Epic has flagged off a show called Drishti, featuring a carefully curated collection of documentaries. PVR Director's Rare also screens cutting-edge documentaries. Some new pitching forums have sprung up such as the Jio MAMI Mumbai Film Festival and Trigger Pitch. Then there is Calcutta's DocEdge, which, of course, has been around for more than a decade.

One reason for the docu boom, some hold, is that the films have changed - thematically and stylistically - over time. Nilotpal Majumdar, director, DocEdge, points out, "As documentary filmmakers collaborate with foreign funders and travel with their films to international festivals, their exposure to contemporary and stylish content is more." The younger generation also has been exposed to high quality documentaries on the Internet and TV channels, and is therefore more receptive.

"The style of making documentaries is almost fictional today," says Sophy Sivaraman, CEO of the Indian Documentary Foundation, set up four years ago to develop, fund and support documentaries. She cites the examples of Katiyabaaz and Lyari Notes, a documentary by The Rat Race director Miriam Chandy Menacherry on teaching music to children caught in a conflict zone in Pakistan.

Documentary filmmaker Nishtha Jain recalls how the censor board was confused about her award-winning film Gulabi Gang, wondering why it was not fiction. "It is just that documentaries can be made differently today," Jain says. Luckily for her, Gulabi Gang ran in the theatres in eight cities for a little more than a week before the Madhuri Dixit film Gulaab Gang was released.

Intelligent use of funds by filmmakers, keeping in mind the integrity of the telling, makes a huge difference to the quality of the end product. Take the case of Karan Bali's An American in Madras, a biopic of American director Ellis Dungan. Bali was funded by a friend, and found rare archival footage of Dungan shooting on his 1930s-40s film sets in Madras. "I bought the footage from film archives in India and got the rest from the West Virginia State Archives in the USA, which luckily had them, in exchange for free copies of the film," he says. Bali did not scrimp on paying the professionals who worked on the film either. The film was screened at the New York and London film festivals, on Channel 4 (UK) and has done the round of American universities.

These days, even pubs screen documentaries that owners feel would interest their regulars. Film clubs, NGOs, foundations, theatres, Netflix are other options. Netflix picked up the Anurag Kashyap-produced documentary, The World Before Her, showing the contrasting worlds of beauty pageant contestants and women belonging to a militant fundamentalist group.

Abraham of The Cinema Travellers, believes that the VOD is going to stir up the waters. "The appearance of Netflix will also challenge theatre owners to give us better time slots," she says.

If there is one problem that docu filmmakers continue to face, it's lack of funds.

"Filmmakers sell their DVDs to universities abroad for $600-1,000," says Sivaraman. At pitching forums like DocEdge and Trigger Pitch, Sundance Documentary fund or at film marts, the competition is fierce. The Cinema Travellers was pitched at DocEdge and won the best project at the forum, but it did not get any funding.

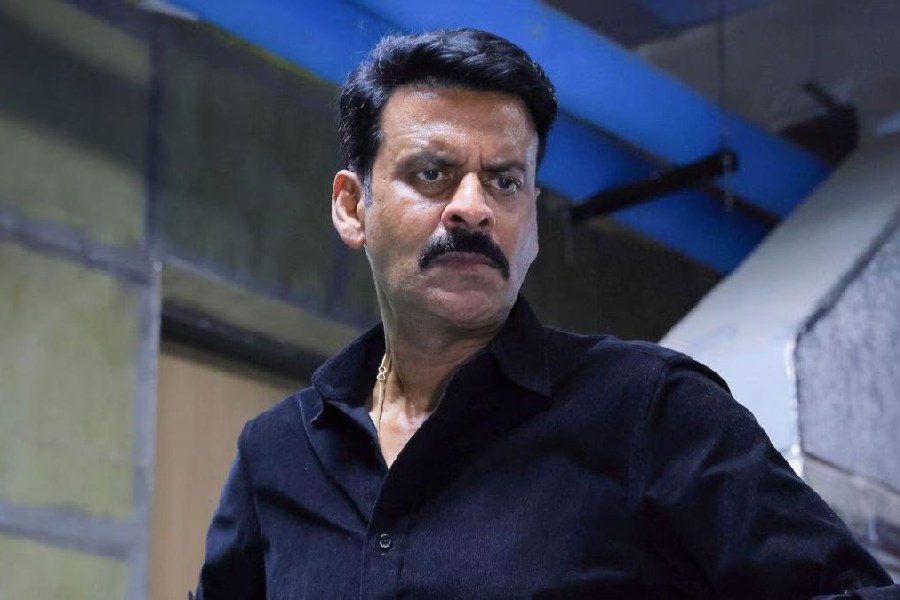

Rinku Kalsy, director of For the Love of a Man, a docu-feature on Rajinikanth's fan clubs, says she and producer Joyojeet Pal put in their own personal savings for the film. Later, they got some funds from the crowdfunding platform Wishberry and an interest-free loan from Drishyam Films that they won at a Goa film bazaar to complete the post-production. "Of late, there is a new market for documentaries on VOD, but compared to the cost of making a serious documentary, they don't cover much," says Kalsy, who is considering a VOD release for her film.

Jain's Gulabi Gang, made on a budget of $3,25,000, had foreign funders. "There is just no money to fund documentaries in India. Epic channel offered me just Rs 1 lakh for three years," says Jain, who has made eight documentaries. Her Lakshmi and Me, on the life of her domestic help, was most successful abroad and telecast twice on the prestigious PBS TV in the US.

Currently, only the Films Division and Public Service Broadcasting Trust fund documentaries with a limited package ranging from Rs 7-13 lakh. And there are strings attached - you may lose your rights over your films and have to depend on the division to send your film for festival screenings.

Jain's documentary was screened in a Mumbai pub and all she got was a free beer for it. "Most screenings are done for free," she says resignedly.

The filmmakers wish television would screen documentaries, as is done in many parts of the world. "Television needs to step in. Great stories are being missed because of this," Bali says.

But with documentaries going places, perhaps it won't be long before television does its bit - and give a long life to a genre that has long been short-changed.