|

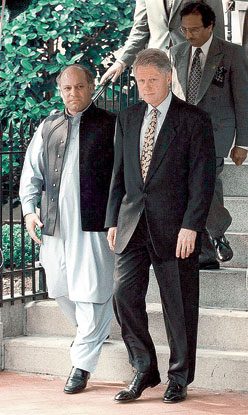

| War and peace: Bill Clinton met Nawaz Sharif in Washington on July 4, 1999, after which Pakistan withdrew its troops from Kargil |

The Lahore dialogue between [Nawaz] Sharif and [Atal Behari] Vajpayee brought a bright moment of hope to South Asia. The BJP leader talked of the “spirit of Lahore” as the beginning of a new day for the two rivals. In Amman, [Bill] Clinton had encouraged Sharif to be receptive and to do all he could to make the visit a success, and Sharif did indeed play the role of a welcoming and encouraging host. The Lahore meeting was a significant step forward…

However, Sharif’s new chief of army staff, General Pervez Musharraf, was not on the same track. Musharraf had come to Pakistan from New Delhi in the great migration following Partition. In the army, he was a hawk’s hawk on India… Musharraf graduated from Britain’s prestigious Royal College of Defence Studies. At the academy Musharraf was remembered for being full of plans for how to win Pakistan’s next war with India. In 1999 he tried, taking the subcontinent to the edge of Armageddon.

Musharraf’s plan was to exploit a traditional stand-down in operations along the northern front line of divided Kashmir province to create a fait accompli that would force India to the bargaining table on Pakistani terms. Just north of the town of Kargil, the line of control, or cease-fire line, between the two armies is located in high mountains and ridges. In what had been the practice for half a century, every winter the armies pulled their frontline troops back from their advance posts to avoid placing the men in extreme weather conditions; in the spring, the troops returned. Musharraf chose to cheat instead, sending his troops under the command of 10th Corps commander Mahmud Ahmed into the empty Indian positions. They moved deeper and deeper, undiscovered, and ended up taking 500 square miles of Indian-occupied Kashmir…

Musharraf apparently gambled that India would sue for peace and agree to negotiations on the status of the province. He was much influenced by India’s successful grab of Siachen fifteen years before, which he regarded as a humiliation requiring redress and as a precedent for his own action.

The problem was that Musharraf did not have a plan B if India refused to give in. If the Indians decided not to talk and to fight instead, they could try to storm the occupied heights or open a new front somewhere else to take pressure off their Kargil positions. In short, India could widen the war. If it did, then Pakistan would find itself facing a broader military campaign and blamed for starting a dangerous new conflict. And that is what happened.

|

Former Pakistani heads of state, including Zia [ul-Haq] and Benazir [Bhutto], had previously rejected such risky plans for precisely that reason. A big unknown about the 1999 Kargil war is how much Prime Minister Sharif knew about Musharraf’s plans before General Ahmed implemented them. After the fact, Sharif and Musharraf, who came to despise each other, disagreed about what the Prime Minister was told. It is unlikely that Musharraf told him nothing but equally unlikely that he expressed concern about the possibility that the plan would end in disaster since Musharraf fully expected a glorious success. Even today he still argues that it could have worked out fine if Sharif had not lost his nerve. The full truth may never be known…

The Indians were caught completely by surprise, and so were the CIA and the US government... Musharraf used what became a false dawn of a new day to cover his preparations.

But he had completely miscalculated the Indian response. Once the Vajpayee government was fully briefed on the military situation by the commander of the army, General V. P. Malik, it ordered a counteroffensive at the point of the attack. Malik organised a brilliant series of assaults on the Pakistani position. He also brought in air power, and Indian jets began attacking the Pakistani position, a move that Musharraf and Ahmed had not properly anticipated.

Malik also prepared to broaden the war. He ordered his forces elsewhere in Kashmir and along the border with Pakistan itself to be ready to expand the conflict if his assaults did not produce results. According to his memoir of the war, in mid-June 1999 he told Vajpayee that if “we could not throw the intruders out from Kargil, the military would have no alternative but to cross the international border or the LoC.”…

The Indians took other measures as well. The Indian brigade usually deployed in the Andaman and Nicobar Islands… was moved to the west coast of India and prepared for an amphibious landing in Pakistan. The Indian Navy concentrated in the Arabian Sea and began aggressive patrols that threatened to blockade the port of Karachi and cut off Pakistan’s oil imports. The navy was so aggressive that Pakistan’s navy began providing escorts for oil tankers, and Malik had to caution the admirals “not to start a full-scale conventional war before all three services were ready.” As Malik recounts it in his memoirs, “the juggernaut was moving steadily.”

In Washington, Clinton followed the war with alarm. [Strobe] Talbott and his team went from shuttle negotiations to crisis management. Naturally, given the tests in 1998, the nuclear issue and the risk of a broader war were uppermost on the President’s mind. Some have suggested after the fact that Washington was too fixated on the nuclear issue. Perhaps that was true, but Clinton would have been justifiably worried about the risk of escalation. He was reminded of how World War I had escalated from a terrorist attack in the Balkans into a global war in less than a month, and he worried, of course, that the Kargil war could go nuclear.

On June 16 Sandy Berger, the national security adviser, met with his Indian counterpart, Brajesh Mishra. According to Malik, Mishra informed Berger that “India would not be able to continue with its policy of ‘restraint’ for long and that our military forces could not be kept on a leash any longer.” Berger got the message. Washington went on full alert. The administration’s public statements, which made it clear from the beginning that Clinton blamed Pakistan for starting a dangerous conflict, now demanded an unconditional Pakistani withdrawal to the line of control.

For the first time ever in a Pakistani-Indian conflict, the United States was unequivocally and publicly siding with India. Islamabad was devastated, and New Delhi could hardly believe it. When the Indian ambassador called on me in the White House to make sure, I told him that the United States was fully behind India. Jaswant Singh later wrote that “this was perhaps the first-ever articulation of an unambiguous stand by the US.” Clinton urged Sharif to pull back and sent the commander of CENTCOM, General Zinni, to Islamabad with the message. Panicked, Sharif tried to secure Chinese support for Pakistan’s position. Beijing received him in late June but gave no promise of support... Other countries, including the United Kingdom, firmly backed the US demands. Pakistan must pull back unconditionally. Sharif called the White House and asked to come to Washington for an immediate meeting with Clinton. Clinton’s response was clear: if Sharif came to Washington, he would have to announce a complete and unconditional withdrawal to the LoC. Sharif, now desperate, came on July 4, 1999.

|

The two leaders met that morning at Blair House, the official guest house of the executive mansion. I was the third person in the room for the entire summit. Clinton later read my account and sent me a handwritten note confirming its accuracy; Sharif also privately confirmed every point with me. Before the two leaders met, the “President’s Daily Brief,” the CIA’s daily report to the president, had delivered alarming news to the Clinton team, which was gathered in the Oval Office to get ready to see Sharif. As Talbott later recounted, intelligence indicated that “Pakistan might be preparing its nuclear forces for deployment.” Among the team preparing to see Sharif “there was a sense of vast and nearly unprecedented peril.” Some would argue later that the danger was not really that serious. Musharraf, in his memoir, argued that nothing unusual was under way in the Pakistani nuclear forces... Indian commentators also tended to diminish the risk. Some have noted that Clinton never mentioned the intelligence to Vajpayee, which is true. Clinton hoped that by the time that he and Vajpayee talked later in the day, Sharif would have backed down and agreed to withdraw from Kargil; he saw no reason to alarm New Delhi further. Both Jaswant Singh, then foreign minister, and General Malik note in their accounts that on its own India had detected unusual activity in Pakistan’s missile forces. Singh says that they saw evidence of Pakistan “operationalising its nuclear missiles,” and Malik refers to “intelligence reports about the Tilla Ranges being readied for possible launching of missiles.”…

Clinton confronted Sharif directly with his concerns about the nuclear menace when the two met alone (with me as the only note taker) the morning of July 4. Clinton said that he was worried that India and Pakistan were taking a horrible risk: getting into an escalation of the conflict similar to the one that the Soviet Union and the United States stumbled into during the Cuban missile crisis in 1962. He asked Sharif whether he knew how far along his military was in preparing for nuclear conflict. Sharif was evasive.

Clinton pressed harder: “Do you recognise what even one nuclear bomb would mean?” As Talbott recalls, “Sharif finished the sentence: ‘…it would be a catastrophe.’” Clinton was now very direct. He gave Sharif a choice. If he would announce the immediate withdrawal of all Pakistani forces to a position behind the LoC, the United States would support resumption of the Lahore process between India and Pakistan and urge India to allow the withdrawal to proceed. If not, America would blame Pakistan for starting a war that could end in nuclear disaster. On top of that, Clinton would blame Pakistan for assisting Osama bin Laden and other terrorists. In his memoirs, Clinton notes that on July 4, 1999, he also signed an executive order placing sanctions on the Taliban and freezing its assets. The direct message was to Kabul, but the indirect message was to Pakistan’s army, the Taliban’s and al Qaeda’s protector.

Sharif very reluctantly agreed to withdraw, knowing that he would be castigated at home for giving up Pakistan’s territorial gains with nothing to show for it. Musharraf immediately began a whispering campaign that labelled Sharif a coward, and the move to oust Sharif began. Benazir Bhutto later put it well when she wrote that the outcome of the Kargil war “was the most humiliating moment for the military since the fall of Dacca. A blame game started, and it was just a matter of time as to who would move first against the other.” The Indians were delighted with the outcome, although they were also confident by July 4 that their army had the situation well in hand and that Operation Vijay (Victory) had triumphed. As Malik later wrote, the Blair House summit was a fundamental turning point in US-India relations. A few weeks later, on a visit to New Delhi, I was delighted to see large models of the White House on display in public parks, celebrating America’s intervention on India’s side in the Kargil war.