|

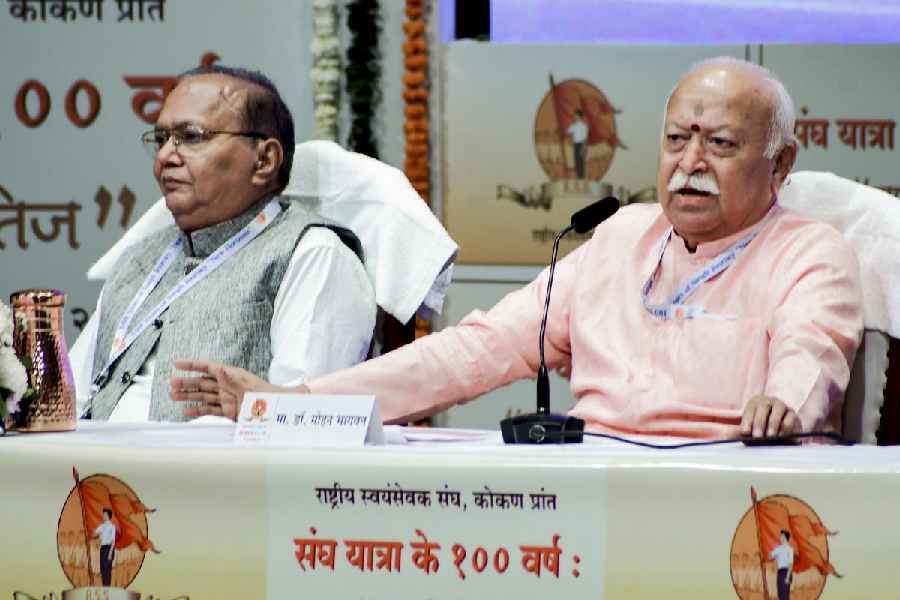

| SINGLE LADIES’ CLUB: Irom Sharmila |

There was anger in Manipur last week. It wasn’t because an innocent civilian was shot dead by trigger-happy soldiers — as has been known to happen in the insurgency-ridden state. Nor was it because essential commodities had vanished from the market — as happened during the economic blockade by Naga militants last year. This time the anger in Manipur was over media reports that Irom Sharmila, 39, who has been on a hunger strike for more than 10 years to get the state to repeal the controversial Armed Forces (Special Powers) Act, was in love and wished to get married.

The reaction seemed to suggest that Sharmila, who had shown such steely resolve for so many years — she is force-fed through a nasal tube — had somehow betrayed the cause by expressing her desire to have a personal life. Conspiracy theories did the rounds too, and some said the publicity given to her affair was actually a plot by the state to deflect attention from her struggle. The subtext of the collective outrage was clear, however. Revered, almost deified, as a shining ideal in Manipur, Sharmila had no business displaying such common human emotions as love. It was a dishonour to her image, an assault on her halo. Indeed, the general sentiment seemed to be — Irom Sharmila, icon and martyr-in-waiting, needs a man (with apologies to that old feminist slogan) like a fish needs a bicycle.

The episode raises one question, though. As a nation are we uncomfortable with the idea of a woman in public service — be it activism or politics — who has a place for love and sex in her life? Is it a coincidence that so many of our successful women politicians are single? Whether it is Sonia Gandhi or Mamata Banerjee, Mayavati or J. Jayalalithaa or Sheila Dixit, the power women of Indian politics are either widows or they never married at all. In fact, some of our best-known women social activists such as Medha Patkar and Aruna Roy are also single. Dowager or virgin, amma or didi, these women are seen to have transcended physical love, and willy-nilly, that seems to up their stock in the public mind.

|

| SINGLE LADIES’ CLUB: Mamata Banerjee, Sonia Gandhi and Jayalalithaa |

Naturally, there are exceptions to the rule. Leader of the Opposition and BJP strongwoman Sushma Swaraj wears her marital badge — the coin of her bindi and her inch-long sindoor — proudly. The Speaker of the Lok Sabha, Meira Kumar, and the President of India, Pratibha Patil, are also married. But they represent the minority in the league of India’s political alpha women. Though the male politicians may have a wife (albeit a suitably invisible one) and even a mistress or two, by and large, we seem to want our women leaders to be asexual beings for them to be credible and, if they are lucky, larger than life.

“It’s the whole Mother India stereotype of sacrifice, sacrifice and more sacrifice,” says social scientist Shiv Visvanathan. “Where Indian women leaders are concerned, the accent is on purity and renunciation. In the case of activists, the demands are even more rigorous. You don’t even have the right to look attractive! And when someone strays from the stereotype, as Irom Sharmila has, the reaction is violent.”

Women politicians are aware of the power of that stereotype. During her electoral campaign in West Bengal earlier this year Mamata Banerjee drew attention to her selfless singlehood repeatedly. She said again and again that the people were her family since she did not have a family of her own. She also took care to repudiate her gendered identity, stressing that she didn’t think of herself as a woman, but as a “human being”. As didi she was only notionally female; she was really the universal protector, just as Tamil Nadu chief minister J. Jayalalithaa was everybody’s amma or mother.

Samita Sen, director, School of Women’s Studies, Jadavpur University, points out that the tradition of leaders practising celibacy or brahmacharya harks back to our nationalist movement. “Whether it was Swami Vivekananda or even Gandhiji (who forswore sex in his later years), many of our nationalist leaders fitted the ascetic mould. Irom Sharmila is more in line with that nationalistic model. She has been fasting for so many years that she has been etherealised, almost deified. So the sudden assertion of her body and her sexuality is disturbing to a lot of people.”

The propensity to deify — and sanctify — a woman leader is, of course, rooted in India’s cultural tradition of worshipping the mother goddess. In another era M.F. Husain had painted Indira Gandhi, that redoubtable Prime Minister (who was a widow), as goddess Durga. It raised a controversy, but perhaps it also reflected the sentiments of a section of the public that idolised her. “Indira is India, India is Indira,” went the sycophantic chant, thus supersizing her and elevating her to the status of a godlike Mother India.

“What amazes me is that even though India worships women, it also heaps such terrible violence upon its women,” says Teesta Setalvad, an activist who runs the magazine Communalism Combat. It is almost as if in order to respect a woman, you need to deify her. The moment she is seen as mortal — an everywoman — she is fair game for contempt and abuse.

Curiously, the Indian public seems more likely to forgive allegations of corruption in their women politicians (both Jayalalithaa and Uttar Pradesh chief minister Mayavati have a history of corruption cases against them) than they are to accept — shock, horror — their love affairs. “But even that is fine, as long as you don’t make it official,” remarks Visvanathan cuttingly. “As long as you construct an acceptable frontstage, you can have sexual freedom backstage. Our middle-class morality is at once coercive and hypocritical.”

Most female activists and politicians admit that the standards for judging women are particularly harsh. “We are very intrusive when it comes to the lives of well-known people, and that is even more true in the case of women,” says Kiran Bedi, once a top cop and now a tireless social activist. Agrees Nirmala Sitharaman, national spokesperson of the BJP, “The bar is raised for a woman, whether it is in her personal life or her professional one.”

However, few would go so far as to say that a solo status works in their favour. “Whether you are single or married is not crucial to your popularity. What matters is the delivery of good work,” asserts politician and activist Jaya Jaitley. Others, like Subhashini Ali of the CPI(M), point out that even if they are single, many of our women leaders are not without their associations with men. More often than not, they are either daughters or widows or protégés of powerful politicians. Jayalalithaa was mentored in the realpolitik of public life by then AIADMK supremo M.G. Ramachandran and Mayavati received the mantle of the Bahujan Samaj Party leadership from Kanshi Ram.

But these back stories fade into irrelevance before the image of the potent, self-sufficient single woman who is seen to dedicate her life to serving the people. Indeed, singlehood, and its attendant aura of self-denial, holds such appeal in public life that it lends a sheen to male leaders as well. Three of India’s most popular male chief ministers — Gujarat’s Narendra Modi, Bihar’s Nitish Kumar and Odissa’s Naveen Patnaik — are single, as is activist Anna Hazare, the ersatz Gandhi who has now attained messianic proportions.

That said, the demand for “virtue” is clearly much more stringent in the case of women. Will that change? Why not? In the 16th century England’s Elizabeth I was glorified as the Virgin Queen. It took a few hundred years for the visibly married Margaret Thatcher to come along by popular choice. No doubt, we too are getting there.