|

Time was when Amish Tripathi (he has now trimmed his name to just Amish), who had a day job as a banker, could not find a publisher for his book Immortals of Meluha. He went on to self-publish it and the rest is history. Today, after the phenomenal success of his Shiva trilogy, he has been paid an advance of Rs 5 crore by Westland for his next book. Incidentally, he has not even begun to write that book.

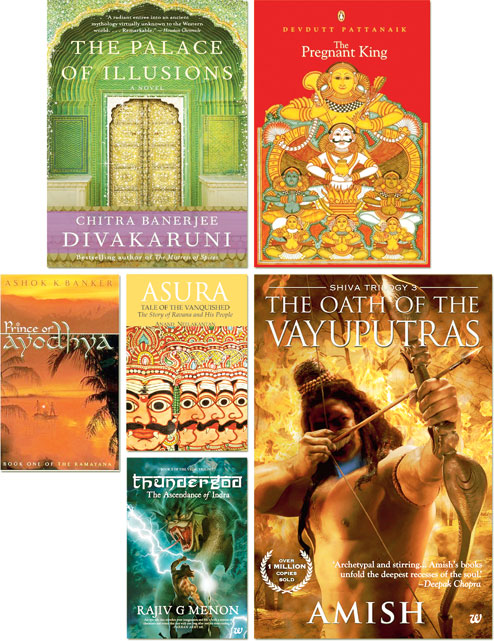

But it’s not just Amish who has struck gold mining the rich treasure house of Indian mythology. A raft of writers is vying with one another to go back to myths and legends and giving them a thoroughly non-traditional twist. And readers seem to be loving it.

The purist may consider the twists to be somewhat far out. If Amish’s Immortals of Meluha envisages Lord Shiva as a tribal Tibetan leader who lived around 1900 BC, in Anand Neelakantan’s Asura: The Tale of the Vanquished, Ravana rants about why his death is celebrated when all he did was to challenge the gods for the sake of his “daughter Sita” and free a race from caste-based rule. And in Ashok Banker’s recently published Epic Love Stories, he wonders if King Dushyanta really did forget Shakuntala or if he had “complex” reasons for not contacting her.

|

|

| Write choice: Amish (left) and Ashok Banker |

Other mythology-based books are also doing well. Among them are Banker’s Ramayana, Mahabharata and Krishna series, Sangeeta Bahadur’s Jaal – Book 1 of the Kaal Trilogy, an epic about a superhero rooted in Vedic concepts of how the world was created; and Samhita Arni’s take on Sita’s disappearance, The Missing Queen. Then there are writers like Manil Suri who has used mythology as a metaphor in his book, Death of Vishnu.

“The tradition of borrowing from Indian mythology is not new,” says Gautam Padmanabhan, CEO, Westland Ltd. He gives the examples of M.T. Vasudevan Nair’s retelling of the Mahabharata through Bhima’s eyes in Randamoozham or Chitra Divakaruni Banerjee’s take on the character of Draupadi in The Palace of Illusions. Devdutt Patnaik’s Pregnant King and Shashi Tharoor’s Great Indian Novel were also based on mythology.

“Mythologies in fiction are now money spinners,” he admits.

Vaishali Mathur, senior commissioning editor at Penguin, feels that Indians who have grown up on a diet of mythology want to read these stories in a “contemporary format”. Having published Devdutt Patnaik’s Pregnant King, she says that the main difference between the earlier mythology-based books and the more recent ones is that the latter are in the fantasy and thriller genre.

What seems to have touched a cord with readers is that many of the well-known tales have been turned on their heads. So the anti-heroes become heroes, and the gods become humans prone to using expletives like “s***” and cheesy pick-up lines like “I feel as if I know you from somewhere.” Many of the characters have been thoroughly contemporarised too. For example, in The Missing Queen, Kaikeyi has been envisaged as a cigarette smoking, chiffon-and-pearls clad dowager.

So why are readers, especially young readers, flocking to these thoroughly modern reinterpretations of our mythology?

Perhaps readers like to question the beliefs and ideas in our myths, and explore what “might have been” or could be, says Divya Dubey of Gyaana Books. It could also be that young Indians today wear their Indianness more lightly and are therefore not too rigid about being faithful to the traditional stories, say other publishers and writers.

“Earlier, Indian English writers used to write fiction for Western audiences with an eye on the Booker,” says Mumbai-based Anand Neelakantan, who is now planning a two-part series on the events of the Mahabharat as told from Duryodhana’s point of view.

“Moreover, we write in simple English aimed at readers who regard English as an Indian language,” he adds. Neelakantan’s Asura: The Tale of the Vanquished was reportedly among the top three biggest selling books at Crossword last year.

However, Amish feels that the popularity of this genre lies in mythology being part of our DNA. “We are just reviving an ancient tradition of modernising and localising myths that have existed for thousands of years. Look at the 100 different interpretations of the Ramayana. The north goes by the Ramcharitmanas, which is a 15th century version of the original Ramayana by Valmiki. Myths will die if you don’t reinterpret and localise,” says the author.

Truth is not what you should be looking for in these interpretations, says Amish. Of his retelling of Shiva’s story he says cryptically, “Only Lord Shiva knows the truth.”

Ashok Banker, who was one of the early practitioners of this mythology fiction wave, says, however, that his Mahabharata stories are culled from the original Sanskrit version by Vyasa. “I scrupulously adhere to the original text,” he asserts.

Naturally, everyone has to do considerable research to churn out these fictionalised mythologies. Anand Neelakantan, who has been looking at the “villains” of our epics in a sympathetic light, reveals he reads the epics in translation and also other scholarly works on them. Chitra Divakaruni Banerjee admits to have read many versions of the Mahabharata for her book Palace of Illusions. “I chose the first person narrative since it allows readers to understand Draupadi’s thoughts and feel close to her,” says Banerjee, who is now keen to write a book on the “misunderstood Sita”.

Despite the commercial success of these books, not everyone is ecstatic about the current craze for “modernising” our myriad myths. As Banker points out, “What the retellings have done is to over-simplify everything. Our original tales are much more complex, subtle and nuanced. Everything is not cause and effect, it’s a number of things acting at the same time as well as free will at work.”

But clearly readers are not splitting too many hairs. They are lapping up these reworking of well-known stories. And with authors and publishers laughing all the way to the bank, few are complaining.