|

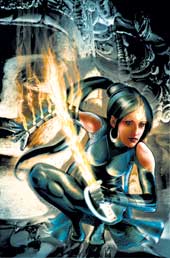

| PICTURE PERFECT: Virgin Comics’ Devi (above) and the cover of the graphic novel version of Agatha Christie’s The Murder of Roger Ackroyd |

|

Move over Superman and Batman. Hercule Poirot is out to give all caped crusaders a run for their money. Agatha Chrisitie’s diminutive Belgian detective can now be found exercising his supercharged little grey cells in — you guessed it — comic books.

In July, Eurokids International, publisher of Tintin and Asterix comics in India, launched 13 Agatha Christie murder mystery titles in the graphic novel format. HarperCollins UK followed suit soon after, and both got the rights to do the books — in India and the UK, respectively — from the same French publisher that already had these Christie graphic novels out in print.

Agatha Christie aficionados may be shocked to see Poirot and Miss Marple thus transformed. But in coming out with these titles, Eurokids has only been tapping into the Indian readers’ growing interest in graphic novels. And it’s not just the kids who are feasting on the exploits of superheroes. A number of adult readers are now snapping up serious American or European graphic novels that cost upwards of Rs 1,000. What’s more, they are keeping a keen eye on what indigenous authors have to offer.

The term “graphic novel” loosely refers to comic books that have a sequential story, with a beginning, a middle and an end. Though some sneer at it, calling it a pretentious marketing term to lend an air of gravitas to what are essentially comic books, graphic novels have come to signify works that are usually more mature and complex than traditional superhero fare or comic strip funnies. Indeed, in Europe and the US, where the art form has a near cult following, some of the best graphic novels can be highly literary, allusive and symbolic. Says Abhijit Gupta, professor of English at Jadavpur University, Calcutta, who teaches graphic novels as part of the university’s undergradute English course, “In the West some of the best literary talents are working in the graphic novel form.”

India’s input into this thriving genre has so far been negligible, and more or less confined to the Amar Chitra Kathas and Chacha Chowdhurys of yore. But that is changing. After the critical and commercial success of Sarnath Banerjee’s pioneering graphic novels Corridor (2004) and The Barn Owl’s Wondrous Capers (2007), the country’s next to non-existent graphic novel universe has suddenly burst into life.

HarperCollins will soon publish Kari, a work by debutante graphic novelist Amruta Patil. A dark, coming-of-age novel, Kari is about an androgynous woman who is saved by a sewer after a suicide attempt. Trained at the School of the Museum of Fine Art, Boston, Patil has written and illustrated Kari herself and is already planning her second graphic novel which, she says, will be based on a “mytho-historical tale”.

Pinaki De, a graphic designer and illustrator who works for top line publishing houses such as Penguin, HarperCollins and Permanent Black, is also putting the finishing touches to his first graphic novel. His is a complex murder story set in the time of mass murders, that is, Partition. De, who has a day job as an English teacher in Calcutta’s Uttarpara College, hopes to publish his work by early 2008.

There have been other initiatives as well. Phantomville, a small publishing house co-founded by Sarnath Banerjee, recently brought out its second graphic novel, Kashmir Pending. Written by Srinagar-based Naseer Ahmed and illustrated by India Today artist Saurabh Singh, the novel has won critical plaudits for its stark depiction of alienation in a land bedevilled by militancy.

And there are countless others throughout the country — writers, artists and illustrators — who are hard at work on their storyboards, melding image with text to tell a dramatic story and push the boundaries of narrative convention. Even a well-known novelist like Samit Basu, author of such works as The Simoqin Prophecies and The Manticore’s Secret, has been seduced by the medium. Basu has written eight issues of Devi, a graphic novel series by Virgin Comics, and is now working on three new comic book lines. He admits that it’s an exciting arena. “It’s new, fresh and unexplored. So when Virgin asked if I was interested, I thought this was absolutely what I wanted to do,” he says.

Launched last year, Virgin Comics — which is a tie-up between Richard Branson’s Virgin Group and spiritual guru Deepak Chopra’s son Gotham Chopra — already has several graphic novel series up and running. With names like Sadhu, Snakewoman and so on, most of them are in the fantasy or superhero mode. But what is significant is that they are all rooted in the Indian ethos.

Naturally, the welter of activity in the field has got mainstream publishers interested. “Sarnath’s novels have sold very well,” says V. Karthika, publisher, Harper Collins, India, who was earlier with Penguin, which published Banerjee’s works. “And there’s a lot of new talent. We are certainly keen on doing good graphic novels,” she adds.

But though there is so much of creative energy flowing into this medium, everyone agrees that we are nowhere near to achieving the sophistication — both in terms of theme and artwork — of such classics as Art Spiegelman’s Pulitzer Prize-winning Maus, or Neil Gaiman’s cultish The Sandman series, or Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis — a wise and funny account of her growing up in post Islamic Revolution Iran. As Amruta Patil says, “We are just taking baby steps here.”

Of course, it is not easy to bring out a highly accomplished graphic novel — one that combines nuanced writing with polished art work. If it’s a one-person show, he or she has got to be a many-faceted talent. “One needs to be multi-skilled, have a firm grip on text and images — independently and both of them together. A good understanding of editing and a ear for dialogue are also important,” explains Sarnath Banerjee who has written and illustrated his books himself.

Since one person rarely has all these skills, many successful graphic novels, including the hugely popular Manga comics in Japan, are collaborative efforts. But meaningful collaboration between two or three persons requires greater investment on the part of the publisher. “That has not really happened here as yet,” says Abhijit Gupta. In any case, producing a quality graphic novel is an expensive affair and needs to be backed by good printers and publishers, he adds.

Some say that India’s publishing houses should set up separate divisions dedicated to graphic novels. For instance, the Random House imprint Pantheon is solely devoted to the publication of these works. But that kind of patronage may not come the way of Indian graphic novels just yet. For in spite of the spike in reader interest, the number of enthusiasts is relatively small even now. “It is still culturally elitist to read graphic novels,” says Banerjee.

But perhaps the biggest challenge before Indian writers and illustrators is to come up with an original idiom, one that’s free from overtones of Western mythologies or the superhero conventions of the Marvel or DC Comics variety. “We need to tell our own stories,” stresses Patil.

Indeed, many of them are trying to do just that, because they feel, as Gupta does, that the graphic novel is really the literary genre of the future. “In a few years you will see a lot of quality graphic novels coming out of India,” he predicts.

Meanwhile, you can go and check out those Agatha Christie numbers. They’re not quite magnifique, as Hercule Poirot would say, but hey, everybody loves a halfway decent comic book!