|

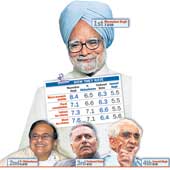

India’s best finance minister is... Prime Minister Manmohan Singh, of course.

That’s always been the common perception but his fellow economists had not endorsed the point — till now. They’ve rated him the best finance minister India has had after 1991, when the Congress government led by P.V. Narasimha Rao ushered in sweeping economic reforms. Still, they've given him just 7.5 out of 10.

Current finance minister P. Chidambaram (Singh’s successor from 1996 to 1998 during the United Front government), follows several notches below, with Yashwant Sinha (finance minister in the Bharatiya Janata Party-led 1998-2002 National Democratic Alliance regime) snapping at his heels. Jaswant Singh (2002 to 2004), who was finance minister for only a year and a half, trails, with one economist refusing to rate him.

Sixty economists in academia and companies all over India were asked to rank the four post-1991 finance ministers on 10 yardsticks, on a scale of 1 to 10 (1 being the worst and 10 being the best) and give an overall rating. Many refused, others agreed but later didn’t respond, a few simply didn’t reply to e-mailed questionnaires. Some gave an overall ranking, but weren’t confident of rating the four on individual parameters. Finally, 26 economists responded.

Most Left-leaning economists declined to participate in the poll. Praveen Jha, economist at New Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru University, (who participated) said there is little to choose from among the four. “All of them followed a neo-liberal macro policy framework (which sees growth as the best antidote to poverty), even though it has been discredited time and again across the world,” he argued. Liberal economist Bibek Debroy, who also participated, felt it would be better to rate individual budgets than finance ministers. The Manmohan Singh of 1991, he points out, was quite different from that of 1995, when political compulsions forced him to slam the brakes on liberalisation (the Congress had lost several state Assembly elections in 1994 and the party’s socialist caucus blamed reforms). Similarly, Chidambaram’s first stint at North Block (which houses the finance ministry) was vastly different from his present tenure. Prime ministers H.D. Deve Gowda and I.K. Gujral gave him a free hand. “Now there is an additional source of budgetary pressure,” says Debroy, referring to UPA chairperson and Congress president Sonia Gandhi’s interventions on behalf of the aam-aadmi. Every finance minister, he notes, has had some good and some bad budgets.

The litmus test, says Surjit Bhalla, managing director of [x]us Investments and an outspoken economist, is how effective the policies a finance minister steered have been in transforming the economy. “By a long shot, it is Manmohan Singh who has been able to do that,” he insists.

Understandably, Manmohan Singh scores highest on addressing macro-economic stability (8.4) and freeing industry from controls and improving the investment climate (8.3). In 1991, India was close to defaulting on its international loan repayments. Reviving growth without fuelling further inflation was a task he adroitly managed. His successors have only had to build on his groundwork.

None of the finance ministers scored very high on fiscal consolidation (ensuring that the government spends within its means) though Singh again scores the highest here. It was left to Yashwant Sinha to put in place a fiscal responsibility policy framework, in the form of the Fiscal Responsibility and Budget Management Act. His successors — Jaswant Singh and Chidambaram — reaped the benefits, with the fiscal and revenue deficits sharply dipping since 2003-2004.

Sinha is a bit behind Chidambaram on most parameters. If Chidambaram slashed personal and corporate income tax rates and further loosened controls on industry and foreign investment, Sinha started an overhaul of the excise duty structure, restructured food subsidies and began the process of reducing the interest rate on small savings.

The one issue on which Sinha ranked the same as Manmohan Singh is disinvestment (the official euphemism for privatisation). Manmohan Singh flagged off the process in 1991 by selling small amounts of the government’s equity in public sector undertakings. Sinha dared to utter the dreaded word privatisation in his first Budget speech.

The privatisation process (steered by Arun Jaitley and then Arun Shourie during the NDA government) has come to a virtual standstill under the UPA government. That is why Chidambaram scores the lowest here, even though he set up the Disinvestment Commission when he was finance minister in the United Front government.

Much of the success of a finance minister depends on his equation with his Prime Minister. Sinha was the only one who suffered here — it is no secret that he was not Atal Behari Vajpayee’s first choice for the post (Vajpayee’s choice was Jaswant Singh). It is this, says Debroy, which hampered him.

But Manmohan faced no such problems. The Prime Minister held him in high esteem — a sentiment that was shared by the middle classes. And now, it transpires that even economists believe that there’s been no one quite like him. Dr Singh, they hold, is numero uno, give or take a fiscal deficit or two.