As a cancer specialist, Dr Mohandas K. Mallath has seen it all. But he still remembers how helpless he felt a couple of years ago, when he met Dr Kumar (name changed). Her husband, a middle-aged doctor like her, had a rare form of cancer. The Kumars had spent Rs 6 lakh in just one year on the treatment. They had to slowly sell most of their assets to meet the high cost of cancer treatment.

'Her ornaments disappeared during each follow-up visit for review. Arms barren, there was only a mangalsutra hanging on a thread around her neck during one visit,' recalls Dr Mallath, who has been working at the Tata Medical Centre (TMC), Calcutta, since 2012. For 24 years he had been at the Tata Memorial Hospital (TMH) in Mumbai and had witnessed the struggles of countless such patients.

These cases inspired the oncologist to explore the socio-economic context of cancer in India as part of a commission of global cancer experts. Their series of papers published last month in the journal Lancet Oncology focused on the escalating cost of cancer treatment and its impact in the country.

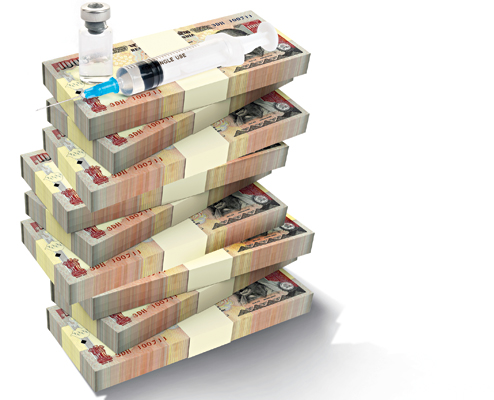

Ironically, as treatment for cancer gets better and better, most Indians are finding it more and more difficult to fight the disease, thanks to exorbitant drug prices and multiple diagnostic tests.

Take the case of Rubeena (not her real name). She was 29 when she discovered she had breast cancer. Within months, the malignancy had spread to the whole of her right breast. The breast was removed, but she is still undergoing treatment a year after the tumour was detected.

Her life can be saved. A drug called herceptin, marketed by Swiss pharmaceutical company Roche, is extremely effective in battling this type of cancer. But each injection costs Rs 80,000 — 10 times the sum her husband earns from his Unani medicine store in Burdwan's Raniganj every month. And Rubeena needs 12 such shots.

Rubeena's parents sold their land to raise money for her treatment. Her sister says they have already spent Rs 6 lakh on an Indian version of herceptin, called herclon, and another Rs 4 lakh on surgery, chemo and radiotherapy.

The growing economic burden of cancer affects not just people below the poverty line but also the middle class, stresses Dr Mallath.

Abdur Rahman, 35, who was a sales executive with a multinational firm, knows that. He has spent over Rs 2 lakh on treatment, food and lodging since he tested positive for leukaemia less than a year ago. The family has decided to sell their land at hometown Malda to meet the cost.

It's not just the mounting cost of drugs that is driving cancer patients or their families to the brink of bankruptcy in India. Says Dr Kesavan S. Nair of the New Delhi-based National Institute of Health and Family Welfare, 'Because of a lack of access to government hospitals, private health facilities are the first point of contact for almost 50 per cent of cancer patients, And the cost of diagnosis and treatment for cancers in private hospitals is enormous.'

For instance, the treatment of head and neck cancer (the commonest form of cancer after breast cancer) usually costs Rs 20,000-25,000 a month in government hospitals. The same treatment can cost over Rs 1 lakh in a private hospital.

A few years ago, a survey conducted to estimate the cost of cancer treatment at the All India Institute of Medical Sciences (AIIMS), New Delhi, showed that, apart from the hospital fee, other costs are incurred — on drugs, investigation and other treatment (such as radiotherapy), and indirect costs (food, lodging and transport expenditures of the patient and kin). These can add up to quite a tidy packet. Says Abhiroop Mukhopadhyay, an economist at the Indian Statistical Institute, who conducted the study, 'Even in a public hospital like AIIMS, the indirect expense often exceeds the cost of therapy — sometimes by as much as 59 per cent,' he says.

According to Nair, three out of four patients delay their treatment for financial reasons. 'Currently, limited financial protection is available from the government in the form of health insurance or financial assistance for the treatment of cancer. Even then, many patients are not aware of the existing schemes for poor patients. Our study has shown that the lack of awareness has become the major reason for not availing of financial support,' he says.

Dr Mallath is even more concerned about the growing number of the elderly at the outpatient department of TMC. 'A recently retired army officer found his dream of settling in his country home shattered after he was suddenly diagnosed with cancer. The cost of treatment is rapidly depleting his savings and he is at the mercy of his family and friends.'

In many cases, cancer strikes after 60, when a person has retired. So treating it eats into a patient's life's savings. For most seniors, cancer treatment is not covered by medical insurance and they do not get adequate financial support from children. 'Some patients hesitate to ask for money — it's a 'prestige issue' for them,' he says.

According to Dr Mallath, less than 10 per cent of Indians can afford modern cancer treatment and the supportive therapies routinely used in developed countries. 'After almost 30 years of experience in treating cancer patients, I have only seen things go from bad to worse for the common man. Government facilities have remained more or less the same and the patient load has increased several fold,' he says

Dr Reena Nair, a clinical haematologist at TMC, Calcutta (formerly at TMH, Mumbai), says that she saw patients and their kin putting up on pavements because the high cost of treatment meant they could not even afford to stay in subsidised lodges.

Yet it cannot be denied that new tests (positron emission tomography), surgical methods (stereotactic radiosurgery) and new drugs have substantially improved cancer survival rates in the developed world. The five-year survival rates for breast cancer in the West have gone up to 80 per cent from 50 per cent a couple of decades ago. The advent of imatinib, dasatinib and other such drugs ensured that death from chronic myeloid leukaemia (CML) dropped 10 times to 2 per cent.

Although most of these brand new drugs are prohibitively expensive, Indians have access to their generic equivalents — thanks to reverse engineering by Indian pharmaceutical companies. But, says Dr Chanchal Goswami, a Calcutta-based oncologist, 'Most poor patients can't afford even these generic drugs.' He laments that India's huge pool of researchers could have easily produced original molecules which might have turned into affordable drugs for its poor citizens (ironically, the leukaemia drug dasatinib named after an Indian origin researcher Jagabandhu Das as his critical contribution led to the development of the drug).

Dr Paul Sebastian, director of the Regional Cancer Centre (RCC) in Thiruvananthapuram, underlines the vast difference in the cost of using branded drugs for treatment and using generic drugs. 'A patient who completes six courses of chemotherapy with branded drugs would have spent approximately six to seven times more. If one adds, as in the case of breast cancer treatment, a branded hormone tablet which is to be consumed orally for five years, the cost of treatment works out to be 75 times more expensive,' he says.

Multinational pharmaceutical companies argue that drug prices are high because of escalating research and development (R&D) costs. But health activists are not convinced. 'More often than not, pharmaceutical companies bear only a tiny fraction of the R&D cost in the early stages or come in only at the final stages of drug development,' says Leena Menghaney, India coordinator for Access Campaign of Médecins Sans Frontières (MSF). In the early stages of developing new drug molecules, much of the R&D work is done in public laboratories or universities.

Some experts question even the need for expensive drugs. They believe that such drugs are not essential for curing cancer — what's needed the most is surgery. 'But the pharmaceuticals industry uses dubious medical data to convince patients and doctors about treatment,' Calcutta-based oncologist Dr Sthabir Dasgupta says.

Surgery, oncologist Dr Paul Augustine stresses, is the best treatment for over 80 per cent of cancers which are 'solid cancers'. The additional professor of surgical oncology at RCC, Thiruvananthapuram, adds that costly drugs can only 'marginally' improve the outcome. Dasgupta believes expensive tests suggested by doctors (such as PET-CT or mammograms) too are often unnecessary. These tests can turn a patient's family into paupers before the treatment begins. And a substantial number of these investigations are ordered by non-specialists who have little knowledge of cancer.

The government is slowly sitting up. The Union health ministry has prepared a Rs 15,855-crore plan for early cancer diagnosis and treatment over the next five years, a 500 per cent budgetary increase over that earmarked for the 11th Plan. By 2017, India plans to open two national and 20 state cancer institutes, along with 100 tertiary cancer centres.

It will be a while before such measures bear fruit. Till then, Dr Kumar will keep selling all that she owns.

Pocket pinch

Breast cancer

Surgery: Rs 75,000-Rs 1 lakh

Radiotherapy: Rs 1-1.5 lakh

Chemotherapy (with herceptin): Rs 56,000 per course; 12 or more cycles may be required, taking costs to about Rs 6.72 lakh

Indirect costs (stay, food, transport) Rs 1-2 lakh

Total: Rs 8-10 lakh

(Breast cancer is the most common cancer among women)

Head and neck cancer

Surgery: Rs 1-1.25 lakh

Radiotherapy: Rs 1 lakh

Chemotherapy (with erbitux): Rs 1 lakh (per cycle; 7 or more cycles may be required, taking the cost to Rs 7 lakh)

Indirect costs (stay, food, transport) Rs 1-2 lakh

Total: Rs 10-12 lakh

(Head and neck cancer is common among men)