Khurshid Mahmud Kasuri is a realist. His book, Neither a Hawk Nor a Dove, makes that clear. But even he wanted to hear some "good news" before leaving for India to promote his book. "There has been so much gloom and doom in recent months that I just wanted a silver lining," says the former foreign minister of Pakistan.

The good news, ironically, came from the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh (RSS). After two days of googling and scanning Indian news sites, a research assistant in Lahore fished out an RSS statement comparing India and Pakistan to the Pandavas and Kauravas of the Mahabharata, and urging the Indian government to develop friendly relations with its neighbour.

"It is a very significant statement. Even the RSS realises that hostilities cannot go on forever," Kasuri says. At the same time he admits that he is probably clutching at straws, considering the slew of aggressive statements emanating from both sides of the border.

"But the message comes from what we in Pakistan consider the spiritual guru of the BJP. So I am sure Prime Minister Narendra Modi will listen to it. It's okay if we are called the Kauravas," Kasuri says, and laughs.

Isn't that ironical - that he is seeing a beacon of hope in a statement that recalls an epic war when, according to him, Islamabad and New Delhi were close to finding solutions to all thorny issues, including Kashmir, when he was foreign minister?

"I am also an optimist," he replies.

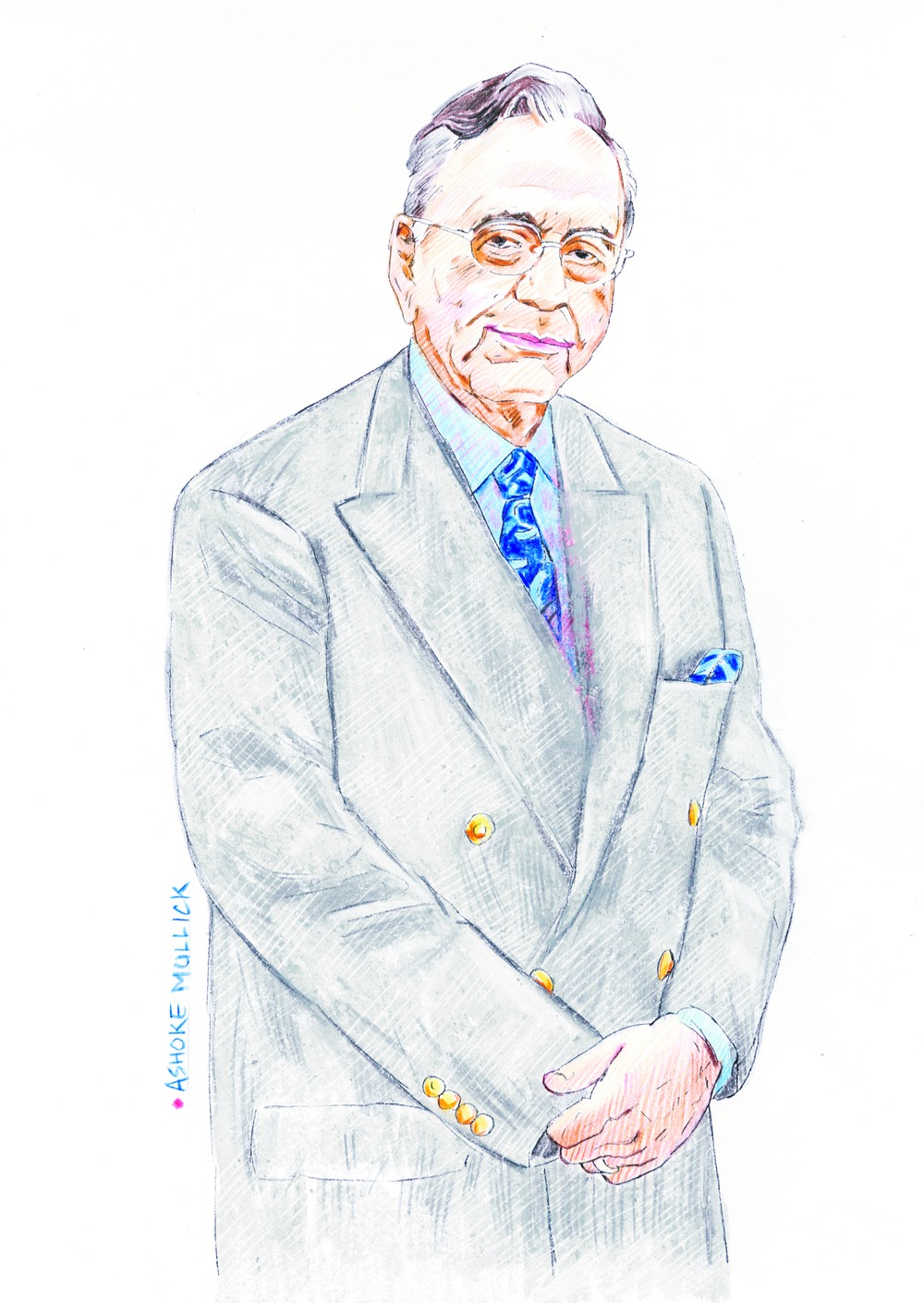

The swagger of the mid-2000s, when politicians of both countries thought that they were about to write history, is missing. Kasuri, who led the peace train from Pakistan to India, is now 10 years older. But he looks buoyant in a dapper, dark-blue, three-piece suit with a mustard coloured tie and a silk scarf peeping out of his coat pocket as he walks in for his interview at the stately banquet hall of a five-star hotel in central Delhi.

The 74-year-old former minister is known for his tidy sartorial style. He was once called the "best-dressed man" in Pakistan by a friend in the presence of former Prime Minister Zulfiqar Ali Bhutto. "Bhutto clearly didn't like it as he thought that the title belonged to him," Kasuri says and bursts into a deep-throated laugh again.

Kasuri is in India to promote his 851-page book that he took four years to write. Like most decision-makers who turn authors, he places himself right in the middle of events. He tells the story of the two neighbours during his tenure as Pakistan's foreign minister from 2002 to 2007.

He was in the thick of things, as the leaders of the two countries worked for peace. There were secretive back-channel talks between India and Pakistan, cricket ties were on an upswing, cultural exchanges were frequent, travelling to Pakistan was easy and Jammu and Kashmir didn't seem such an insurmountable problem.

"That period was actually the most productive in the independent history of both the countries. I thought it appropriate to record it so that people do not say that I was fibbing," Kasuri says about his book.

Former foreign minister Yashwant Sinha has confronted him on some of his assertions regarding back-channel discussions between the two countries, but Kasuri says confidently that he is ready to be contradicted by anybody who was privy to the talks. "But nobody can. I have written the truth," he says.

It makes him "very sad" that India and Pakistan are once again lashing out at each other. "You travel from Lahore till the Wagah border and then you cross over to Amritsar and you listen to the radio on both sides. You will hear exactly the opposite of each other. This cannot last," he says.

Recalling his days as foreign minister and talks with his three Indian counterparts, Yashwant Sinha, K. Natwar Singh and Pranab Mukherjee, he says that the political leadership then was willing to take risks for results. "Nothing will get done between India and Pakistan unless people in power stick their necks out and start taking risks," Kasuri asserts.

N<ot that it was a smooth ride even during those years of hope. Kasuri mentions how he tried to convince several Kashmiri leaders to go along with the India-Pak talks and failed and how there were attempts on General Pervez Musharraf's life for his peace overtures. He also recalls how a pall of gloom descended on Islamabad after the 2004 general election results in India.

"We were quite upset when the Vajpayee government lost. We thought that we had invested a lot in our relationship and the upward trajectory had just begun," he says. "But Dr Singh filled the shoes beautifully," he adds.

Kasuri is concerned about the current situation between India and Pakistan. He shifts in his chair to explain what he means. "There has to be a positive impetus for the relations to go up," he says and makes his right hand take off like a plane. "Or they are bound to go down if there is no impetus," he says, now gesturing a nosedive.

His friends in India tell him that Modi may not warm up to Pakistan any time soon, but he feels that the Prime Minister would have a "sense of destiny". "I think Modi may not stick with the current situation. I think he will seize the moment," he predicts.

And he has a piece of advice for Modi. "Please appoint a back-channel operator without announcing one. Let him go around and see what both the countries have on their minds. And at the end of four or five months, if there is progress, both countries can say that back-channel diplomacy is at work," he says.

Enough work, he adds, was done during the Vajpayee and Manmohan Singh years and the threads could be picked from there. "I think we know each other's bottomline on every issue plaguing this relationship. Everybody knows the limits to which the 'deep state' or establishment can be pushed," he says.

The biggest "missed opportunity" for a historic breakthrough, he believes, was in the August of 2006 when Manmohan Singh postponed his visit to Pakistan. In six months, Pakistan was caught in the grip of a spiralling lawyers' movement, which finally led to the ouster of President Musharraf.

Many in India blame Pakistan for not willing to return to the table on issues that were agreed upon when he was the foreign minister. Kasuri in turn blames Asif Ali Zardari who took over as President from Musharraf in 2008.

"He was days into office as President when he announced that Pakistan would soon hear good news on Kashmir. He was probably briefed about the progress we had made and he went overboard and raised expectations. That was very foolish. We haven't recovered after that," he says.

But he hopes that statesmen will come along the way to shape a better future. "I wouldn't have wasted four years writing this book if I was not confident of the future," Kasuri says.

And he draws a cricketing parallel to make his point about bilateral relations. "India-Pakistan relations should be played like a Test match. The game should last for 10-15 years in this case. Let governments change and get a handle of the situation. But talks should continue." He then quotes his friend Mani Shankar: Talks that are "uninterrupted and uninterruptible".

Kasuri, along with some of his family members, is now a part of former cricketer Imran Khan's Pakistan Tehreek-e-Insaf party. And he says that the former Pakistan captain agrees with him "100 per cent" on the way forward for peace with India.

The ex-foreign minister himself belongs to an illustrious family of undivided Punjab. His grandfather Maulana Abdul Qadir Kasuri headed the Indian National Congress's Punjab wing for many years and as a freedom fighter spent years in jail. His father Mahmud Ali Kasuri was only 19 when he was arrested for participating in the Quit India movement.

His father, Kasuri adds, is regarded as the "father of the human rights movement" in Pakistan. The senior Kasuri resigned from Bhutto's Cabinet in 1973 soon after he realised that Bhutto had "dictatorial" tendencies.

Would his father have approved of his son's stint in Musharraf's Cabinet? "You must understand that we belong to different eras. Moreover, I joined Musharraf only after he was elected President," he replies.

Kasuri was arrested during dictator Zia ul Haq's regime and spent a few months at the Lahore Central Jail. And with a sense of history, he requested the jailor to put him in freedom fighter Bhagat Singh's cell - which he did.

As a student of history, he speaks passionately about how Pakistan has gone too far in "ideologising" its history. "We have murdered history and we are paying a very big price for it," he says. And then, pointing a finger at me, he adds: "Even you are re-writing it now. India will also pay a heavy price if you write history to suit ideologies. Narrow-mindedness will not help in a country's growth."

His looks at his book that looks more like a dictionary because of its size, lying on a tea table separating us, and asks if I have read it. I reply that I have gone through some relevant portions. "Mark my words. What I have mentioned in this book will be the basis for future talks between the two countries," he says, putting great emphasis on the words. The old swagger, I can now see, is still there.