At the start of Zed Plus, a political satire ("It went totally unnoticed"), Dr Chandraprakash Dwivedi, the director of the 2014 film, has a tongue in cheek disclaimer in his own voice. It opens with the usual phrases - the events and characters in the film are fictional and any similarity to a person living or dead is purely coincidental - but ends with a twist. "One cannot even imagine that events depicted in the film can happen in a democracy like ours," he intones.

Will his coming film Mohalla Assi have a similar disclaimer and a last line that states: "One cannot imagine that events depicted in the film can ever be associated with the holy city of Varanasi"?

He laughs out aloud. "Maybe, maybe. If it is released," he says, and laughs again.

Someone leaked an unapproved trailer of Mohalla Assi, set in Varanasi, a few weeks ago. The clip made its way to YouTube. The 2.4-minute video peppered with Hindi profanities mouthed by actors such as Sunny Deol and Sakshi Tanwar has clocked more than a million hits.

Most filmmakers would be happy about a pre-release buzz, but not 55-year-old Dwivedi. "I used to only hear the expression ' Jeena haram ho gaya hai' (life's hell). I am experiencing it now," he says, shaking his head. He goes on to add that whoever leaked the unedited portions of the film as a trailer "played with fire".

Dwivedi has received so many threatening calls that he no longer responds to unknown numbers. "These days there are too many thekedaars (caretakers) of religion, culture and history and they jump to conclusions too soon," he says. The film is based on a popular Hindi novel called Kashi ka Assi by Kashinath Singh. "The novel has many more expletives than the film," he points out.

Religious organisations have accused Dwivedi of hurting Hindu sentiments and also of depicting Varanasi in a "bad" light. Several police complaints have been filed across the country and a Delhi court has even banned the film.

He has become a pariah, he says, for many people who he thought were friends. One such friend called from Varanasi last week to say that he would be joining a group of people to file an FIR against Dwivedi.

That must be hard for somebody who burst into the national scene as an upholder of "cultural nationalism" through his television mega hit Chanakya in 1991. Dwivedi, who is seen as being close to the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP), played the role of Chanakya - author of the Arthashastra - and also directed the series when he was 30.

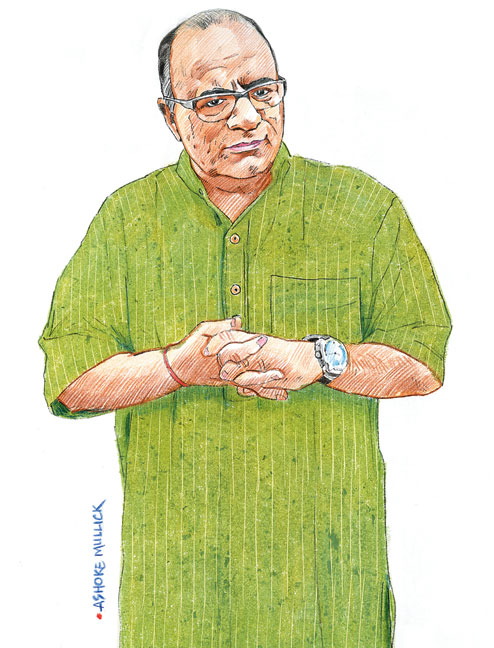

His face doesn't look as craggy as it did in Chanakya and he is no longer as lean. "I was supposed to look ugly as ancient texts say that Chanakya was not a great looking man. So we took close shots of my face. Now people look at me and probably think that I have undergone cosmetic surgery. They don't notice that I have put on weight and so has my face," he smiles.

I am at his office in Andheri (West), Mumbai. The reception area has large posters and cut-outs of Zed Plus. Just behind it, people are busy on their computer terminals. Among them is his wife of 17 years, Mandira. She has just scanned the day's newspapers and updates Dwivedi on what the dailies have been carrying on Mohalla Assi.

"There's something or the other every day on the film," she says, as Dwivedi leads me up the stairs to his room on the mezzanine floor of his office.

In one corner of the floor stands a huge shelf of books. Right next to it is a collage of his photographs, gifted to him on his birthday a few years ago by his daughter and wife, with handwritten messages under each one of the pictures. Mounted on one of the walls are a framed National Film Award certificate (for national integration) and a medal that he won for his 2003 film Pinjar.

Dwivedi is now busy preparing his defence in case the certifiers raise objections to the language in Mohalla Assi. "Did you know that ancient texts mention that profanities please the Indian gods of fertility," he asks and goes on to quote from ancient texts where cuss words have been used, also mentioning how they were a part of yagnas and festivals. He points to the bookshelf and lists the numerous books that he has collected as part of his research.

Amember of the Central Board of Film Certification (CBFC) himself, Dwivedi is confident of being able to convince the board when he represents himself as a filmmaker. "We should not create a culture of bans. We need to have global standards for cinema when it comes to film certification," he stresses.

He says that if an adult certificate is granted to his film, one should let cinemagoers decide on the merits of the film. "If you are above 18 and can choose your government, why can't you choose your film," he asks.

He should be confident about his persuasive powers as Dwivedi cut his teeth as a young director of a big budget television series at the height of the era of red tape in Doordarshan in the late Eighties and Nineties. " Chanakya was initially rejected by Doordarshan after they watched a pilot episode produced at a cost of Rs 18 lakh way back in 1988. That was a huge amount of money then," he recalls.

He started writing 30-page letters to Doordarshan arguing why Chanakya was relevant to Indian history and how they had no reason to reject it. "I used to quote from various historical documents on the importance of Chanakya," he says. Doordarshan finally said yes after he found sponsors.

The show was aired when communal frenzy was at its peak, with the Ram Janmabhoomi movement - for a temple in Ayodhya in place of a mosque - gaining ground. Trouble for Dwivedi and Chanakya began after Episode 11, sometime in 1991. "There was a scene in which students of Takshashila are shouting Har Har Mahadev and placing saffron flags in opposition to Alexander the Great. Flags and slogans unsettled many in Delhi," Dwivedi says.

He remembers how a very senior Shiv Sena leader called him up to say: "You have hoisted a saffron flag on Doordarshan for the first time in Independent India." Dwivedi knew he was in trouble.

Soon, Doordarshan informed him that there could be no saffron flags or slogans. And the series was restricted to 26 episodes from the initially approved 52. "Some felt that it was Hindu propaganda. They felt that the Rashtriya Swayamsewak Sangh was behind the whole thing. The irony was that nobody from the Right came to my help," Dwivedi muses.

As for political leanings, Dwivedi says that while he has been identified with the BJP for many years, he is not political. "I will not hesitate to say that many of my friends are from the RSS and the BJP. I have never been political. But I like the idea of India. And I also believe in cultural nationalism," he says.

A doctor by training, Dwivedi practised the profession for exactly one month and 28 days. Born into a family of Sanskrit scholars, literature attracted him rather than medicine. "I always wanted to interpret literature on the screen. I realised that this was my first love and stopped my practice," he says. Not entirely, though: "I do treat people from my film unit whenever they have minor ailments."

As we head out to a restaurant for lunch in the neighbourhood, a few people notice the short-statured Dwivedi - wearing a long dark green shirt with tribal art embossed on it, paired with beige trousers. But they recognise him as "Chanakya" - not as an artiste who has quite a body of work.

Dwivedi dabbled in television serials for a few years before he decided to direct a film. Pinjar was based on Amrita Pritam's novel on post-Partition trauma. The film was well received by critics and also won him a National Award, but there was controversy here too.

"Some people said that I was presenting the Hindu view in the film as I had shown an RSS person distributing food to refugees from Pakistan. I didn't care as Amirta Pritam herself said that, and I was very faithful to the novel," he argues.

He returned to television in 2008 with a mega serial Upanishad Ganga based on Mughal prince Dara Shikoh's interpretation of the ancient texts. "That was very close to my heart, but not many people watched it," he says with a hint of disappointment.

Dwivedi has just finished a documentary on the river Saraswati: "Many people believe that Saraswati is a mythical river. We have tried to prove that Saraswati indeed existed."

He realises that there are reasons people see him as a flag bearer of Hindutva. "You look at my body of work and the controversies and people can think like that. But I cannot help it. I don't know what people will say now as the ones who thought I was their own are protesting against me and threatening me," he says.

The director advocates patience. "Wait for the film's release before declaring me guilty in mohallas, street corners and tea shops," he stresses. In an increasingly restrictive space satirically described as "Ban-de-Mataram", he may be asking for too much.