|

FIVE DAYS BEFORE HE KILLED himself, Lokesh told his friend that he had put his failed love affair out of his mind and had mentally moved on. “Lokesh had been heart-broken when the girl he liked said she wouldn’t marry him. He started smoking and his grades dropped,” recalls Vishwanath S., a final year student at Bangalore’s Kidwai Memorial Institute of Oncology, and Lokesh’s class fellow.

After a long patch, Lokesh, who had just turned 22, got back to a normal schedule, and even applied for a masters degree in hospital administration at Manipal University. But it just took three days for all plans to go awry. Last week, Lokesh tried calling his former girlfriend. She did not answer his call. Two days later, after a practical class, Lokesh picked up a bottle of Pavulon — a muscle relaxant drug — from the hospital’s operation theatre. At night, he injected the drug in his arm and died within a few minutes.

Fourteen people committed suicide in Bangalore in four days in May, half of them in the 15-25 age group. The Silicon city recorded 2000 suicides in 2006 and 843 in the first four months of 2007, according to police records. “The suicide rate in Bangalore is three times higher than that in any other city,” says G. Gururaj, head, department of epidemiology, National Institute of Mental Health and Neuro Sciences (Nimhans), Bangalore .

Elsewhere, too, more and more young men and women are committing suicide. While West Bengal has the dubious distinction of the state with the highest number of suicides, the number of deaths in the 15-29 age group in the state is also on the rise, increasing from 2370 in 2003 to 3002 in 2006. Hanging and consuming pesticide are the two most common methods of suicide.

Joydeb Das of Calcutta was just 22 when he killed himself after seeing his former girlfriend on the pillion of another man’s motorcycle. He tried to meet her, but was rebuffed. He went back home and hanged himself.

A failed love affair is one of the reasons why the young take their lives. But most drive themselves to death because of academic frustrations. “Come competitive exam time and I get flooded with students who think their lives have lost all meaning since they have not cracked the IIT or the JEE,” says Rima Mukherji, consultant psychiatrist at Crystal Clinic in South Calcutta .

A day before Lokesh killed himself, a Bangalore-based MBBS student, N. Rashmi, consumed 30 phenobarbitone pills — which are prescribed for epilepsy — and died. Rashmi wanted to do a post-graduation in paediatrics but failed to get the subject of her choice.

In Delhi, the past few weeks have been hectic for Abdul Mabood, director, Snehi, an NGO working in trauma counselling. “We get 2,200 calls every week from students anxious about their board exam results,” says Mabood. Many stress that they are suicidal.

Last year, Nimhans released the results of a suicide survey in Bangalore which found that 64 per cent people who ended their lives in 2005 were below 39 years of age. Out of every three cases of suicide reported, one was by a youth in the 15-29 age group. “There is a marked increase in suicide happening among the urban youth. The numbers have quadrupled in the last few decades,” says Gururaj.

For Satish Sharma’s parents, these figures aren’t just cold statistics any more. The 17-year-old student of a Delhi school hanged himself to death two weeks ago after failing his standard X examination for the third time.

THE EXAM RESULTS FOUND another victim in Sagar, Madhya Pradesh. When the results were announced, Arpit Choudhary eagerly checked his marks through his mobile phone. When he found that his result was not as good as expected, Arpit locked himself in his room and hanged himself.

Exam-time suicide has almost become a trend in India . A study on suicide among adolescents in South Delhi found that 56.4 per cent of adolescent suicide are reported between March and July. “Parents and teachers do not develop a crisis mechanism system in children, who collapse under competitive pressures,” says Sanjeev Lalwani, head, department of forensic medicine, All India Institute of Medical Science (AIIMS), New Delhi, and author of the study.

Brendan McCarthaigh, a Calcutta counsellor who runs SERVE (Students Empowerment, Rights and Vision through Education), points out that prestige in society determines success or failure in any particular activity. “The rising cases of suicide among the youth is an indication that we are persistently failing in our efforts to provide them a reason for a meaningful existence,” says McCarthaigh.

Behind these very individual tragedies are some rapidly changing social processes. “Success and wealth are worshipped in today’s society. So, young people find failure harder to handle,” says social scientist Ramachandra Guha.

Rapid economic growth has also fuelled young ambition. “India’s economic success story has resulted in escalating aspirations. Young people feel they can achieve anything and want instant gratification. When they don’t, they get impatient and instantly frustrated,” holds Gururaj. The Nimhans study found that 57 per cent of youth suicides were sudden acts of frustration.

There is a marked north-south divide in suicide trends in India . The economically progressive and rapidly urbanising southern states record a higher incidence of youth suicide.

IN APRIL 2004, BRITISH medical journal Lancet published a study conducted by doctors at the Christian Medical College (CMC), Vellore, Tamil Nadu, on teenage suicide. The study produced startling results. It found the teenage suicide rate in Vellore was 148 per 100,000 for young girls and 58 per 100,000 for boys.

To put this in perspective, the average global teenage suicide rate is 14.5 deaths per 100,000 people. “The rate of suicide among young girls in Vellore was 100 times higher than that in Britain,” says paediatrician Anuradha Bose, a co-author of the study.

Kerala’s suicide rate is three times higher than the national average. “In one day, 26 people take their lives. Of this, 80 per cent are teenagers,” says Rajasekharan Nair, secretary, Thrani, a Thiruvananthapuram-based suicide counselling centre.

Conversely, Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, which have much higher populations and lower levels of literacy, report a lower suicide rate. In 2002, UP and Bihar accounted for 4.8 per cent and 1.7 per cent, respectively, of the total number of suicides in the country, according to the National Crime Record Bureau.

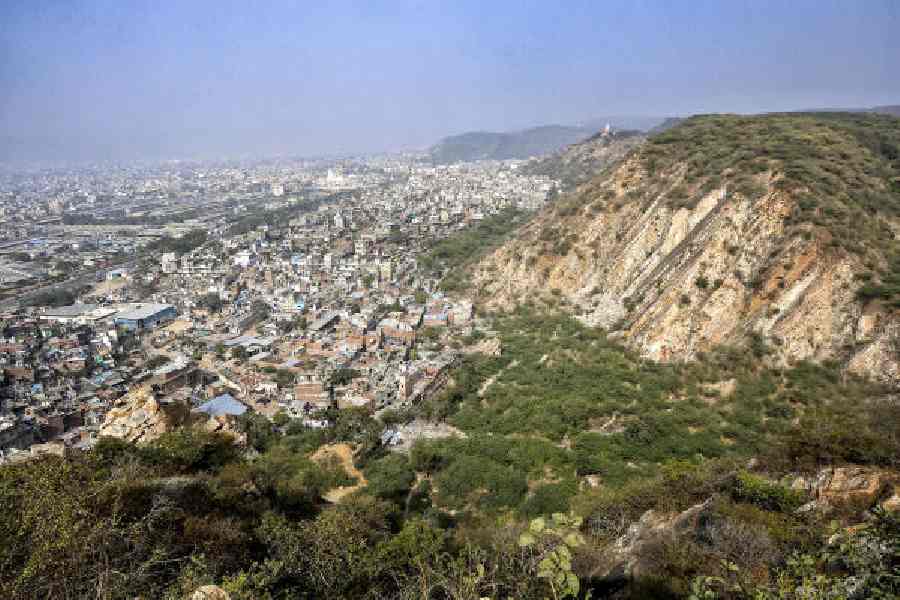

Clearly, rapid urbanisation, large scale population migration and sudden economic prosperity leave scars on the young. Gururaj recalls the case of a 17-year-old boy who moved from orthodox Allahabad to Bangalore to study engineering. “He was dazzled by a new culture of glitzy malls, abundant alcohol and free interaction with girls. Also, he had no family anchoring in Bangalore,” he says. The boy had a failed love affair and his grades dropped. Last year, he consumed pesticide and killed himself.

COUNSELLORS ARE ALSO worried about youngsters accessing suicide chatrooms on the Net, which add to the image of death as a merciful release. “Suicide occurs when death becomes preferable to humiliation or a life bereft of meaning,” says Mukherji.

As young blood spills, suicide prevention strategies are being put in place. Nimhans is advocating a national suicide prevention policy and regularly holds suicide prevention workshops. CMC, Vellore, plans to seek a ban on the sale of lethal Class 1 and 2 pesticides.

SERVE has been trying to promote a less stressful educational model. Snehi in Delhi conducts about 20 workshops every year in the city’s schools and colleges, where parents and students are taught anger and frustration management. “The demand for these workshops has increased tenfold in the last decade,” says Snehi’s Mabood.

Life skill training has become a focus area. The Indian Association of Paediatrics (IAP) has developed a special life skill training module which is taught by trained pediatricians in school across India. “Children are taught to be only goal-oriented. They don’t know how to cope with failure. The IAP module focuses on stress management training, yoga, relaxation and problem-solving techniques,” says IAP member Geeson Unni, author of a book on adolescent life skills.

But for now, suicide is the third largest killer of teenagers in India. And death is just a ceiling fan away.