|

The phones never stop ringing when the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) inserts notices in newspapers urging readers to report corruption and crime. But the incidents that the readers highlight — from a bus passenger’s complaint that a conductor did not return the exact change to a guest suspecting that a junior officer had spent beyond his means at a wedding — are not exactly what the CBI is looking for.

Increasingly, though, there is a feeling that the government’s highest investigative body should perhaps limit itself to petty crimes like these. For, in several high profile cases that it’s been involved in, the CBI has shown at best incompetence, and, at its worst, servility or corruption.

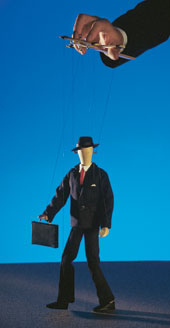

Last week, the CBI was severely reprimanded by the Supreme Court of India which called it a caged parrot repeating its master’s voice. The observations came in reference to the CBI’s inquiry into alleged irregularities in the allocation of coalfield licences.

But many who have fought the CBI believe that it has often exceeded its brief. That’s why lawyer Ranjan Lakhanpal was not surprised when his client Ghulam Ahmed Mi, Jammu and Kashmir minister for tourism — one of the people accused in a 2005 sex scandal involving minors — was acquitted in September, 2012.

“The CBI bungled big time. In the rush to show results and to be in the media spotlight it arrested many innocents,” Lakhanpal says.

Of course, it’s not that the CBI, which turns 50 this year, has never cracked high profile cases. It has, indeed, successfully dealt with a wide range of crime, from assassinations to official corruption. But its inept handling of cases has also seen its reputation take a nosedive.

“For the outside world, the CBI is this great organisation that can solve any case assigned to it, but that’s not the truth. They can be as bad as the state police when it comes to handling cases,” says Vishal Garg Narwana, a Chandigarh-based lawyer who has often taken on the CBI.

Pensioner K.K. Sood knows that well. The CBI had accused the former section officer in the Staff Selection Commission, Delhi, of conspiring with two men while favouring some candidates who had taken an examination for the post of clerks in 1998. In 2012, a Delhi court acquitted all three and directed the CBI to take action against its officers for an “unfair” probe.

“He is a broken man today. He had a clean record but the arrest tarred his reputation forever,” says one of Sood’s close relatives.

The CBI, on the other hand, holds that it has handled many cases with success. Working on an annual budget of Rs 450 crore, its brief is to investigate cases of corruption and economic crimes committed by central government employees. Although it does look into other kinds of cases (from terrorism to murder) when such cases are referred to it. About 30 per cent of the cases it handles are referred to it by state governments and courts.

“The odium that attaches to the CBI is mainly from cases in which politicians and those with political connections are investigated. But such cases constitute just about one per cent of the CBI’s workload,” says former director R.K. Raghavan.

A senior CBI official argues that if cases are not investigated as they should, it’s also because of increasing workload and decreasing staff. In 2012, it had 128 deputy superintendent-level officers as against the sanctioned strength of 265. At the inspector level, there was a shortage of more than 100 officers.

Despite all this, CBI supporters point out, its conviction rate is a healthy 67 per cent. The Maharashtra police, in comparison, has a conviction rate of 8.2 per cent, and Bihar 15.5 per cent. Kerala is close to the CBI with a 65.2 per cent conviction rate. Cases of corruption and misconduct against CBI officials, according to spokesperson Dharini Mishra, account only for a small fraction.

But all rules fly out of the window when politically sensitive cases crop up. “The CBI is comparable to the best in the world when allowed to function freely. But once attached to the apron strings of politicians, they are worse than the worst state police,” holds P. Chandra Sekharan, a forensic science expert who has worked closely with the CBI in several cases, including the 1991 Rajiv Gandhi assassination case.

But efforts are now on to strengthen the CBI. Earlier this week, the Prime Minister set up a group of ministers to work on CBI autonomy. But N. Vittal, former Central Vigilance Commissioner, is still sceptical. “Every government servant is supposed to work independently without fear or favour. Where is the need for autonomy? What we need are men and women of character and integrity and no amount of autonomy will give you those qualities,” Vittal says.

Indeed, it’s because the CBI is seldom allowed to work without fear that its reputation has been tarnished. Recently, it was accused of working at the behest of the ruling coalition in the Sohrabuddin encounter case. The CBI has been widely criticised for chargesheeting Rajasthan BJP leader Gulab Chand Kataria in the case.

Accusations of toeing the government line are not new. The Bofors case of the late 1980s — in which it was alleged that politicians and others were bribed for an arms deal — is a case that never saw closure. Top politicians who were accused in the Jain Hawala case of the 1990s –– relating to alleged campaign contributions — went scot free. The 1992 Babri Masjid demolition case still drags on.

Nor is it just the ruling United Progressive Alliance (UPA) government or Congress that’s been accused of interfering in the CBI’s functioning. When the Bharatiya Janata Party-led National Democratic Alliance (NDA) was in power, the CBI was accused of putting pressure on Bahujan Samaj Party leader Mayawati — who was in the opposing political camp — in a disproportionate assets case. The CBI, it was later alleged, went soft on her once the UPA came to power.

“We may have been there for six years, but the UPA has been in power for the last nine years. Why didn’t they fix the issue and make CBI autonomous,” retorts BJP spokesperson Nirmala Sitharaman.

The demand for autonomy is voiced every now and then. Parliament’s committee on personnel, public grievances, law and justice recently called for CBI autonomy. “Not just this committee, several committees have over the years recommended this. But whether it was the NDA or the UPA, nobody has shown any interest in it,” says committee member Sukhendu Sekhar Roy, a Trinamul MP.

Is it possible for the CBI to work independently? Yes, says Raghavan, provided a few conditions are met. “Withdraw the directive which requires permission to do even a preliminary enquiry against a minister, or an official of the rank of a joint secretary or above,” he says. Second, the rules that demand government sanction for prosecution and for filing an appeal against an acquittal should be amended.

“Give it total financial autonomy. And give the CBI directors a five-year tenure (it’s two years now) and make them ineligible for any post-retirement government assignment,” he says.

But the BJP’s Harin Pathak, who was the NDA minister of state for personnel, public grievances and pensions — the ministry under which the CBI figures — says that no political party has ever been ready to give freedom to the CBI. “Perhaps the time has finally come,” he adds.