|

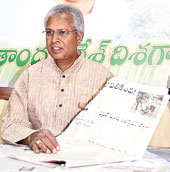

The nub of the problem with Margadarsi Financiers is that it collects deposits from the public which, says Arunakumar Vundavalli (right), Congress Member of Parliament, is illegal, a fact he says he stumbled upon by chance in September 2006. In 1997, a new element was introduced in the RBI Act — Section 45S barred individuals, partnership firms and unincorporated bodies (that is, anything that’s not a company) from collecting funds from the public. Margadarsi, being part of the Ramoji Rao Hindu Undivided Family, is an unincorporated body and so couldn’t collect deposits from the public. According to Vundavalli, Margadarsi had told the RBI in 1999 that it was restructuring the business and would stop accepting deposits, an assurance it did not keep.

An RBI spokesperson declined to respond to emailed questions on Margadarsi. While Ramoji Rao too declined to talk to The Telegraph, citing a lack of time and his involvement in several legal cases, he did explain in his letter to the Editors’ Guild last year that he had obtained legal opinion from two former chief justices of the Supreme Court, Justice P.N. Bhagwati and Justice Y.V. Chandrachud, that Section 45S of the RBI Act did not apply to Margadarsi.

In November 2006, Vundavalli wrote to finance minister P. Chidambaram asking him to investigate Margadarsi, arguing that it was violating the law. He also alleged that it was making huge losses.

The finance ministry forwarded the letter to the RBI which is said to have taken the matter up with Margadarsi. According to a finance ministry press release dated December 1, 2006, Margadarsi assured the RBI that it would not accept fresh deposits or renew maturing ones. In addition, it would deposit any unclaimed deposits in an escrow account and utilise the money received from Blackstone’s investment in Ushodaya to repay depositors. The RBI proposed to monitor the implementation of all this closely.

In December 2006, the state government invoked the Andhra Pradesh Protection of Depositors of Financial Establishments Act. It asked N. Rangachari, former chairman of the Insurance Regulatory and Development Authority (he is also a former chairman of the Central Board for Direct Taxes) and now an advisor to the state government’s finance department, to see if Margadarsi was doing anything detrimental to the interests of its depositors. It also authorised the inspector general, CID, to take action against Margadarsi under the RBI Act. The inspector general later applied for a warrant to search the premises of Margadarsi.

Rao then went to court. In December 2006, he challenged the Protection of Depositors of Financial Establishments Act in the Andhra Pradesh high court and also sought the quashing of the two government orders. When the high court did not give any interim relief, Rao took the battle to the Supreme Court in January 2007. His point — the high court should have stayed the two orders. He also sought a transfer of the cases in the high court to the Supreme Court. In April 2007, the Supreme Court said Margadarsi’s accounts should not be frozen or attached under the Protection of Depositors of Financial Establishments Act. The RBI and the state government could take action only if Margadarsi defaulted on payments to depositors. It also asked for a monthly account of payments made to depositors. In August 2007, the Andhra Pradesh government filed an application asking this order to be vacated. That matter will come up in the Supreme Court this month.

“It is an open and shut case of abuse of power,” says Harish Salve, Rao’s counsel in the Supreme Court. “The state government was trying to provoke a run on the company by depositors and force it into default.” Since this would have affected Ushodaya and Eenadu, in February 2007 Rao requested the Editors’ Guild to implead itself in the matter. The Guild took the stand that it would intervene only if there is interference in the editorial operations of Eenadu. It would let the law take its own course as far as Margadarsi was concerned, since it was a financial entity.

In February 2007, Rangachari submitted his report. This raised doubts about Margadarsi’s ability to repay its depositors. Rao, in his letter to the Editors’ Guild, alleged that the report was prepared in haste, without giving him a chance to respond. Rangachari’s report, however, says that each time Margadarsi was asked to respond to charges it said it had challenged the enquiry in court. Rao’s lawyers counter that Rangachari gave them a February 17 deadline for responses. But even though the Supreme Court had fixed a hearing on February 23, 2007, Rangachari submitted his first report on February 14 and the second and final report on February 19. “The heavens wouldn’t have fallen if he had waited for a week,” they argue. Rangachari, when contacted by The Telegraph, said he has nothing to add to what his report contained.

Rao has pointed out that Margadarsi has never defaulted on payments to its depositors, ever since it began operations in 1972. However, Vundavalli insists that neither this nor Margadarsi’s decision to voluntarily stop accepting deposits absolves it of the charge of collecting deposits illegally or prevents the government from taking action against it even without any complaints being made. “Merely because there is no complaint from anybody against a brothel you cannot say that the government should not initiate suo motu action against it.”

The courts will eventually decide who’s wrong and who’s right.