|

| NOTE THIS: Topiwalleh by Swarathma, a six-member band, deals with issues such as religious hypocrisy and child abuse |

Are the police troubling you? Is your land being taken away? Are you tired of the politician’s corrupt ways? Then pick up the pen — and compose a song. Across the country, writers of protest songs are making their presence felt. From Kashmir and Manipur to Jharkhand and Delhi, local and domestic issues are being turned into music.

“The aim is to let the rest of India know the stories of the marginalised,” says Meghnath, a 57-year-old singer from Jharkhand, whose song Gaaon chhodab nahin (Won’t leave my village… won’t stop the fight) is being echoed in other parts of the country as well.

Protest music in India — once seen as the offspring of the Communist parties — is springing up in all corners of the country. The Indian People’s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was the cultural squad of the Communist Party of India and a repository of protest music, has lost its sheen over the years. Now a band of independent musicians is filling up the vacuum.

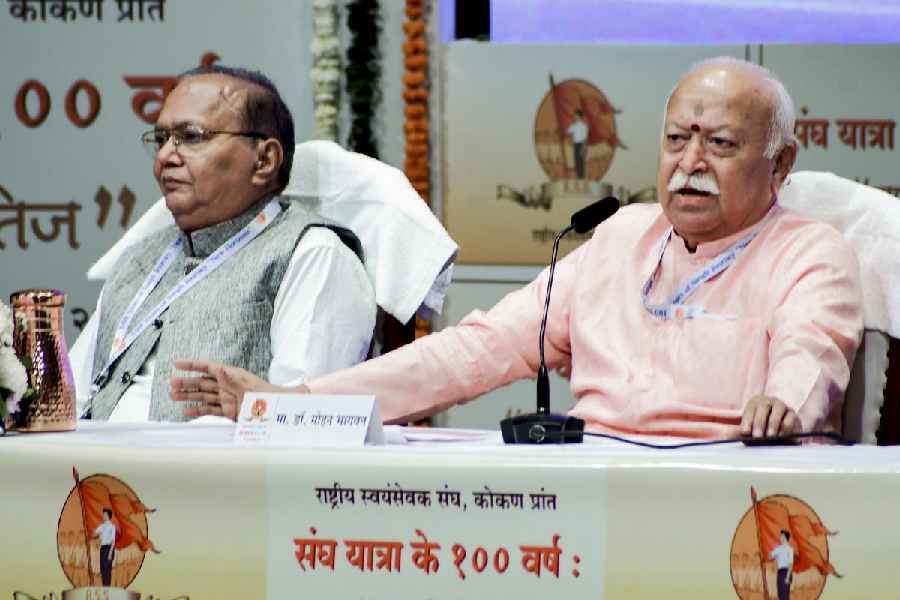

Take the Bangalore-based rock band Swarathma. Its new album, Topiwalleh, deals with the issues of the time. The title track mocks the average politician, while Yeshu Allah aur Krishna exposes religious hypocrisy and Ghum laments child abuse.

“We react to what we see around us. We chose music as the medium to tell people how the world around us makes us feel,” says Jishnu Dasgupta, the bass guitarist of the six-member band.

Or take Akhu Chingangbam. The focus of the Manipuri musician is developments in his state. His song, Eche – Irom Sharmila (My sister, Sharmila), is on the iconic Manipuri protestor’s ongoing fast against the army. The song Qutub Minar talks about stealing the 12th century Delhi monument and transporting it to Manipur. “I suppose we’ll be able to draw the Centre’s attention to Manipur only if we steal the monument and take it there,” says Chingangbam, whose 2009 album Tiddim Road has sold 2,000 copies so far.

Unlike the forefathers of protest music who took up pan-Indian issues such as communal harmony, colonialism or workers’ rights, the new protest music deals with local issues. So Kashmiri rapper M.C. Kash aka Roushan Illahi talks about state repression through his poetry (I protest). And Bant Singh, a Dalit farmer from Punjab, sings about losing land (Assi pahunchna shaheedaan waali manzil — Our destination is where the martyrs dwell).

|

| Cover of an album by Susmit Bose |

“This is my fight against injustice. I want to make the youth aware of the conditions prevailing in rural north India. Mere words don’t attract many ears but music does,” says Bant Singh.

Indeed, the music is gaining popularity in some quarters, though it’s mostly restricted to concerts and video-sharing websites. “Protest songs are popular because they break stereotypes in music,” reasons economist-cum-singer Sumangala Damodaran, who reproduced songs of the IPTA in an album called Songs of Protest along with guitarist Susmit Sen of the band Indian Ocean two years ago.

After the IPTA’s decline, protest music found space in political groups such the Naxalites. Noted among the proponents was Gaddar of Telangana — the bare-chested singer who never failed to enthuse his supporters with his raw voice and simple lyrics.

But if music then was a political weapon, today’s protest singers stress that they have no larger political agenda. In fact, some point out that they don’t promise to bring in change through their music at all.

“If any artiste claims that protest songs are harbingers of change, it is an exaggeration. The idea is to provoke people to think, people who feel that everything is fine in this country,” says Chingangbam, who has a rock band called Imphal Talkies, named after a defunct cinema theatre in Manipur.

Dasgupta adds that he doesn’t have a “solution” to offer to the issues he takes up. I don’t want to tell the world to behave in a certain way. We are here to spark a debate and not to change everything overnight by our songs.”

But 22-year-old Indore boy Puneet Sharma believes in the power of protest music. He was 17 when he wrote his first song — Jawaab ho galat agar, to ruk nahi sawaal kar (If the answer is wrong, don’t hesitate, ask again). “I belonged to a conservative Brahmin family and was never allowed to ask questions. That’s why I wrote this,” says Sharma, who writes songs for Swarathma and is also trying his luck in the Mumbai film industry.

He writes in Hindi, just like the other protest writers who pen their anguish in their own languages. Chingangbam’s songs are in Manipuri and English, while Madhu Mansuri Hansmukh of Ranchi writes in the local Nagpuri dialect. “I am comfortable in expressing my feelings in my local dialect. But this language is similar to Hindi, so reaching out to people is not difficult,” he says.

Delhi-based urban folk singer Susmit Bose prefers to write in English. “My songs tell the rich the stories of the poor. So it is important for me to convey the message in a language that the former understands,” he says.

But the singers complain that marketing or commercially producing their music is not easy. Bose says he prefers to do “guerilla” marketing. “You have to be quite forthright in marketing. I give out CDs to people wherever I sing,” says Bose, who started singing in 1971 and released his third album Man of Conscience in 1990 and then Public Issue in 2006.

Bose, whose 2009 album The Essential Susmit Bose included a song about activist-doctor Binayak Sen, says music companies are not always keen to record protest songs. “Many marketing firms asked me to drop the song. I didn’t,” he says. The album was finally released after Oxfam India, a non-government organisation, funded it, Bose adds.

For some of the songsters, the problems are the reason they write. “I will continue to pen my feelings as long as I live, as long as I feel,” says Sharma.