Did London professor inspire India’s economic miracle?

According to the conventional wisdom I have acquired, Manmohan Singh is the heroic politician responsible for opening up India’s economy when he became finance minister in 1991 after P.V. Narasimha Rao succeeded Rajiv Gandhi as Prime Minister.

But last week I was told that the man who persuaded Manmohan to abandon the bad old socialist way of thinking and embrace the joys of the free market was Bishnodat Persaud, an influential economist whose funeral I attended at Golders Green Cemetery in north London last week.

I was there as a friend of Bishnodat’s eldest son, the well-known psychiatrist Dr Raj Persaud.

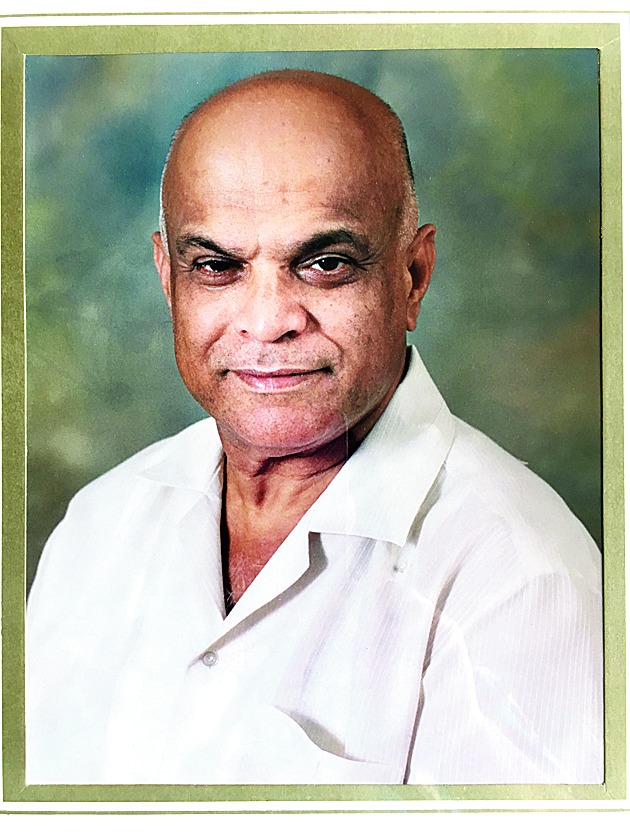

Professor Bishnodat (“Vishnu”) Persaud, who was born in Guyana on September 22, 1933, is said to have had a big but behind-the-scenes impact while working for the Commonwealth Secretariat in London from 1974 to 1992, the last 11 as director and head of the economic affairs division.

He was adviser to the South Commission, an independent economic policy think tank headquartered in Geneva where Manmohan was secretary-general from 1987 to November 1990.

Paying tribute to Vishnu at the funeral service, Sir Shridath Surendranath (“Sonny”) Ramphal, Commonwealth secretary-general from 1975-90, said: “Vishnu’s division helped to advance the world’s economic thinking. And it did so, too, in its shaping of the many expert group reports it piloted like the Brandt and Brundtland and South Commissions. Vishnu’s personal contribution in all this was one of worldwide proportions — a Caribbean scholar whose life had a global reach.”

Vishnu’s second son, Avinash Persaud, who is also an economist, indicated that if “India is now the world’s fastest growing economy”, some of the credit should go to his father who had “many courteous but intense arguments” with Manmohan.

Avinash, currently emeritus professor of Gresham College, said his father was “an advocate of the shift away from the statist model of economic development prevalent in the 1980s. He played a major role in progressing the future finance minister and later Prime Minister of India, Manmohan Singh, along that path.”

He added: “Dad also came across Manmohan when he was the economic advisor to the Brandt and Brundtland Commissions helping to draft the reports. Manmohan was a very reluctant, even an anti-reformer, when Dad met him first, but in the aftermath of a balance of payments crisis there was a vacuum of ideas and Manmohan filled the vacuum with the ideas about greater openness that he got from Dad rather then those coming up from the advisers at the ministry of finance. Over time, of course, Manmohan gathered around himself other local advisors.”

Phone-y ascent

One of the greatest but rarest pleasures of life in north Calcutta is to find a taxi when you need one and then getting it to go where you want to go.

We may soon be robbed of this if a mobile phone application such as Bhavish Aggarwal’s Ola expands further.

He offers everything from limousines to auto-rickshaws and says, “We will leapfrog the phase of car ownership and instead consume transportation as a service.”

Aggarwal and a group of entrepreneurial young Indian men (curiously, all are photographed wearing blue shirts and jeans) are featured in the September edition of Wired in the UK — this Condé Nast magazine is part of the Vogue family.

It seems the whole world is getting excited by the prospect of doing business in India through mobile phone technology. I have also just read a 2,000-word article on it in the Financial Times.

Others interviewed in the Wired article, written by Bangalore journalist Shradha Sharma, include Shashank ND and Abhinav Lal, who have set up Practo to match patients with doctors in 100 Indian cities by the end of this year; and Sujayath Ali, whose company, Voonik, offers nice clothes for women with limited budgets.

I like the sound of Focus Health, set up by K. Chandrasekhar and Shyam Vasudeva Rao. Their flagship low-cost machine, 3nethra (signifying the wisdom of Vishnu’s third eye), allows a technician to place online details of a patient’s eyes for a doctor to make a speedy diagnosis. They reckon they have prevented 3,00,000 people from going blind.

Invariably, all the men — sadly, there appear to be no women doing start-ups — speak digitalese.

Rajiv Srivatsa and Ashish Goel offer 5,000 items of affordable, high-quality furniture through Urban Ladder.

For their customers there is the promise of “enhancing product visualisation through augmented and virtual reality”.

This is in case they want to know what a piece of furniture really looks like.

Dissing David

David Cameron is said to be taking a “gap year” to write his memoirs. Since he has probably been the most pro-Indian prime minister Britain has ever had, we will all be going through the index to see what he has to say about engaging with Narendra Modi and eating street food in Calcutta.

Whatever the book’s merits, it is almost certain to be trashed by reviewers.

Here’s a typical review. Sir Malcolm Rifkind, former Tory foreign secretary, won’t be thrilled with this put down of Power and Pragmatism: The Memoirs of Malcolm Rifkind: “David Cameron’s career may have ended in failure with the referendum result. But Margaret Thatcher’s didn’t, despite her ousting, Sir Malcolm argues. For his part, he aspired to be foreign secretary, and he succeeded. That point is persuasive, and yet not worth waiting 447 pages for. Even if all political lives do not end in failure, some political memoirs do.”

Mayfair man

People in India may not be familiar with Gerald Cavendish Grosvenor, the sixth Duke of Westminster, one of Britain’s leading aristocrats and landowners who died last week, aged 64, after suffering a heart attack.

However, those who play Monopoly will have on many occasions bought and sold Mayfair, the most expensive property in the board at £400.

In real life, it is the Duke who owned 300 acres of Mayfair and Belgravia, two of the capital’s most expensive areas where only Indians can afford to live.

Musical chairs

A tale of another economist, Monojit Chatterji, who admits he has been “playing a bit of musical chairs with academia”.

In addition to all his other posts, he has just become a college lecturer and resident director of studies in economics at Fitzwilliam College, Cambridge, whose Indian alumni include Subhas Chandra Bose; Shankar Dayal Sharma, the 9th President of India; the astrophysicist Jayant Narlikar, known for the Hoyle-Narlikar theory of gravity; and the lawyer Sachindra Chaudhuri.

In Cambridge, Monojit continues to be a Fellow of Sidney Sussex, and also a college lecturer and director of studies in economics at Trinity Hall (where he thinks the food is best).

He and his wife Anjum are taking a three-week holiday in India, and will call, while in Mumbai, on “Aunty Uma” (screen legend Kamini Kaushal) whom he has known “since I was 5!”

Tittle tattle

We all miss “curry king” Lord Gulam Noon. At least, I do. He would have accompanied his wife, Lady Mohini Kent Noon, to Calcutta when she launches Black Taj, her novel set against the background of the Partition, on August 29, courtesy of Sundeep Bhutoria’s An Author’s Afternoon.