A collage of colours - bright blue, yellow and black - welcomes you to Orchha, a small town in the Maoist stronghold of Abujmarh in Chhattisgarh. Coloured tarpaulin sheets drape tables laden with goods set up along the undulating lane that cuts through the dusty town.

Ramesh Usendi holds his chequered blue-grey lungi, fluttering in the wind, with one hand, and with the other fiddles with an MP3 player. He has bought this digital player of Chinese make for Rs 150.

"The shopkeeper downloaded some Gondi songs for me," says the 25-year-old from Jatlur, 30 kilometres from Orchha in Narayanpur district. Gondi is the predominant tribal language spoken in Abujmarh.

In this back-of-beyond pocket - a land caught in a time warp - excitement arrives every Wednesday morning. For this is when the haat comes up, week after week and through the year. People walk from their villages in the hills and forests, often trekking all day and more to travel 45 kilometres or so, to buy - or perhaps just look at - the goods on sale.

There are torches on the tables, LED bulbs, emergency lamps and even selfie sticks. From synthetic clothes and plastic slippers to fashion jewellery and from pencil cells to mobile phones, the market tempts villagers with a variety of goods. Most have a Made in China emboss; the prices range from Rs 50 to Rs 1,400.

Dressed in a fitted red blouse with a green gamchha and a strip of printed cloth wrapped around her thin waist, Santi Gota of Handawada has walked with her two little children through broken roads and crossed two streams to reach what the locals call their bazaar.

She has bought clothes for her two-year-old son and four-year-old daughter, and is now looking at artificial silver earrings for herself, a local interpreter explains. "We wear only traditional brass jewellery. But these artificial ones look different," she says.

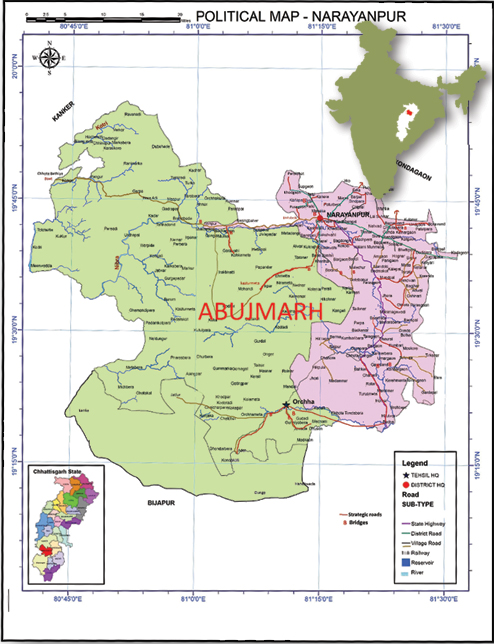

The market, a running affair for more than three decades, is the lifeline of people living in the 237 villages of Abujmarh, a terrain that spans across 4,975 square kilometres. The locals also sell their own produce - brooms, tamarind, Indian gooseberries ( amla), etc. - in the market; this is how most earn a little cash and ease living.

But the market has changed character. There was a time it sold only essentials such as rice, sugar, salt, pulses, spices and utensils. For the past five years or so, it has been flooded with cheap Chinese goods.

The shopkeepers are petty merchants from Narayanpur town, who collect Chinese goods from markets in Jagdalpur and Raipur, and sell them in Orchha, 65 kilometres away. Most of the goods enter Chhattisgarh through Hyderabad, administration sources say. According to some estimates, Chinese goods worth about Rs 300 crore are sold in the state every year.

Attempts have been made to put a curb on them. Chief minister Raman Singh had said recently that the government would ban the sale of Chinese goods. There was an outcry against such goods in October, when Chinese-made halogen lamps apparently burst at a cultural programme in Rajnandgaon district and caused eye injuries to many present.

But Abujmarh is not troubled by such threats. The sellers say that halogen lamps and torches are in big demand because electricity is rare; it embraces but a few rural outposts like Orchha, Godadi and Mandali. "Villagers often buy halogen lamps and torches in bulk for the entire village," says Sunil Singh, who sells the torches for Rs 150 and the lamps for Rs 300 a piece.

The other popular product is the mobile phone. There is no cellular network in the villages, but people like to carry cell phones. "They listen to songs on their phones," says Suresh Soni, another shopkeeper. "Portable radios are in demand. They want to hear the news," he adds.

Some shopkeepers believe villagers often buy radios and phones for Maoists living deep in the jungles of Abujmarh. Over 175 villages of Abujmarh fall under the so-called liberated zone ruled by the Jantana Sarkar, or people's government.

Little is known about this region; it lies cut off from the rest of Chhattisgarh and the country, courtesy an inaccessible geography and the violent politics of Maoist cadres. "The name Abujmarh means nobody knows about anything. It means the area which is unknown, deserted and blank," says a paper called "Orchha, the market within blank space of Abujmarh" by N.L. Dongre.

The forests are thick with mango, tamarind, mahua and peepal trees. The Indravati river cuts off Abujmarh from Bastar, making it even more isolated. Populated by people belonging to the Gond, Muria, Maria and Halba tribes, most Abujmarh villages can be accessed only by foot.

That is why development is not a word that the villagers know of. Government officials have not stepped into the interiors of Abujmarh. Orchha, its headquarters, is one of the few places that can boast of a healthcare centre. Abujmarh has not been surveyed by the government, and there has been no official mapping yet.

One of the vehicular roads to Orchha leads off from Dhaudai in Narayanpur. I travelled about 30 kilometres down this track to reach the market. The curved and pebbled road passes through dense forests of sal, teak and bamboo thickets. By night, this stretch is inky black. The occasional and passing blur of lights are CRPF camps set up along the route.

After an hour of travelling in the dark, a huge pillar with faded murals of a tribal man and woman welcomes you to Orchha.

Orchha, not to be confused with the more famous tourist destination in Madhya Pradesh, springs to life on Wednesdays - occasionally even Tuesday nights - when the stalls are set up. Sometimes, the police stop vendors from setting up shop at night. When that happens, the market opens the next morning.

On an average, some 400 villagers gather in Orchha for the bazaar. They buy essentials such as vegetables and cereals, and Chinese goods that interest them. The place is also a social hub; this is where tribals from far-flung hamlets convene. "For six days a week, they live in isolation. People wait for this one day," says Narayanpur district collector Taman Singh Sonwani.

The stalls also tell the villagers about new technology, or of changing trends. For instance, people for generations in these regions have cooked food in utensils made of clay or bottle gourd skin. Now they buy aluminium pots. If they ate mostly boiled kodo kutki (millets) and pikhur (a tuber), they are now buying vegetables, oil and turmeric. Stalls selling samosas and jalebis do brisk business.

Though many tribal people still wear traditional clothes, an increasing number of men sport shirts or T-shirts and cargo shorts, which they pick up from the market. Once they walked barefoot; now they move around in plastic slippers. Women, who earlier wore just a piece of cloth or a lungi wrapped around their waists, are often seen in saris and blouses.

"We have taught them how to wear clothes," says samosa-seller Nibha Banerjee, who has been setting up a shop in the market for 30 years. Someone called Banerjee? Here? But of course; after the creation of Bangladesh in 1971, a lot many refugees were re-settled in these parts and have since made it their home.

This is also where the tribal people - who usually speak Gondi, Maria and Halba - pick up a smattering of Hindi and English. Some of their children study in schools run by the Ramakrishna Mission or the government. Last year, for the first time, three boys from a village in Abujmarh joined Delhi University.

Muru Ram, a 19-year-old boy who has come to Orchha to buy a chain saw for his father, has studied in a Mission school, and now wants to go to Jagdalpur for further studies. The chain saw is not available, and he is asked to come back after a few weeks.

There are rumours that local Maoists have asked hawkers not to sell Chinese goods. The news is unconfirmed and unexplained, but the shopkeepers are worried. "We will clear the stock and not pick up fresh ones. But we will run into losses if we don't sell Chinese goods," Soni says.

Ironically, the sale of Chinese goods is the only issue on which the Maoists and the Centre are on the same page.

For the villagers of Abujmarh, China perhaps is no longer a symbol of guerilla warfare with the promise of revolution. It now stands for lights, phones, batteries and music, for profitable commerce and ease of life, no more.

ABUJMARH: LOST IN TRANSITION

• Area: 4,975 square kilometres, mostly unmapped and inaccessible.

• Stretch of metal road: 54 kilometres

• Population: 34,950

• Maoists (rough estimate): 500

• Security forces: 800 across six camps (Orchha, Dhanora, Basingbahar, Kurusnar, Akabeda and Kukdajhor)

• Security personnel killed between 2012 and 2016: 11

• Maoists killed: 36

• Government schools: 135 across only 30 villages

• Schools destroyed in 10 years: 50*

• Healthcare centres: 6 across 5 villages; 42 had been sanctioned

• Healthcare centres destroyed in 10 years: 12*

*No damage to schools and healthcare centres in the last 5 years

Source: Government and police in Narayanpur and Orchha