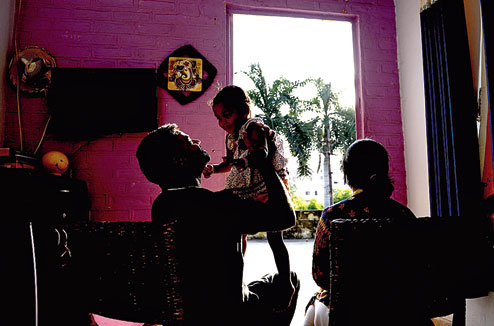

The one-room house in Savina, a lower-middle class locality in Udaipur, isn't fancy. One big bed is all there is for furniture. The most visible aspect of the room is the number of racks jutting out of the walls. Parts of it filled with images and idols of Hindu deities, the rest stacked with pots, pans and jars containing much of their daily essentials.

This is the house Prince calls his home.

Clad in a pair of jeans, a jumper and a light sleeveless jacket as the mid-October nip begins to make its presence felt, the three-year-old skirts around his aai and baba - mother and father - as Bhagwatilal and Santosh lay down snacks and take the plastic chairs Santosh brings in.

"Prince has brought all the happiness you see in this house. We don't have much, but everything we have is his," Santosh says.

But there's a catch. The couple cannot write his name as Prince in official documents - his school papers, doctor's records, or his birth certificate. Neither can Bhagwatilal and Santosh name themselves Prince's parents.

In another life, the boy is called Pritham, son of a minor unwed mother who gave him up shortly after his birth.

About a year ago, Bhagwatilal and Santosh brought Pritham home under the foster care programme introduced in 2014 by women and child development (WCD) minister Maneka Gandhi under the Juvenile Justice (Care and Protection) Act.

"We had been wanting to adopt a child for nearly two years and when we finally got Prince, minor irritants such as having the right to name him, or have our names on his birth certificate didn't matter," says Santosh, adding, "He is ours now."

Santosh is only being hopeful. Under law, Prince - or Pritham - is the ward of the Rajasthan government and the child care institution that has taken him in.

Bhagwatilal and Santosh are among only seven couples in the country who have opened their homes and hearts to children like Pritham, without any expectation and rights - an act, even otherwise impassive government employees call a selfless service. "Couples who opt for foster care are people who want to just rear a child," says Veena Meherchandani, superintendent of the Government Specialised Adoption Agency (GSAA) in Udaipur, the nodal adoptions outfit in Rajasthan.

Had it not been for Bhagwatilal and Santosh, and the other six families in the otherwise conservative state, children such as Prince would not have known a home - or an aai, a baba or a family. In a country that saw 3,877 adoptions - 3,011 within India and 666 inter-country adoptions, according to the WCD ministry - in 2015-16, the year he was taken in by his aai and baba, Prince would have been like thousands of other children left behind in state institutions, growing up without a family, and many without an aim or objective in life.

Foster Care, the brainchild of Maneka Gandhi, aims to move such children out of institutional care into homes. "My endeavour has been to ensure that all children get family care; the concept of foster care has been a step in that direction. I am happy to notice increasing acceptability of this new concept in Indian families," says Gandhi.

While Pritham is legally free for adoption - he has been rejected twice by prospective adoptive parents due to a minor problem in his neck - under law, his foster parents can only move to adopt him after they have fostered him for at least five years.

On the other end of Udaipur in the middle-class locality of Panchwati, another couple is struggling to come to terms with the similar lack of permanence.

Satish Gupta, a chef at an Udaipur restaurant, and wife Avantika, are fostering Arisha, now two, for the last six months. "What we are doing is uncommon and is not easy to explain. It is a very tricky road, but we feel blessed because she has changed our lives," Satish says. The couple, both hotel management graduates, have moved from their rented house in Udaipur since Arisha arrived.

"This is primarily a vegetarian city and our daughter loves fish and chicken. So we had to find a place where the landlords did not have a problem," Avantika says.

Avantika comes from Calcutta, and obviously relishes their daughter's eating habits. "She is also a huge fan of Dev (the popular Bengali actor and Trinamul MP); she sings his songs effortlessly," she says, and then both mother and daughter break into a giggle.

But deep in their hearts Avantika and Satish know that Arisha is not free for adoption, as her birth mother, being mentally challenged, is not in a condition to waive her rights.

"The only way such children can be placed for adoption is if the physician can sign on a certificate that the parent will never get well. No doctor would normally do that, so this child is never going to be legally free unless the mother expires," says Devashish Mishra, programme manager with Jatan, a non-profit organisation in Udaipur which works closely with GSAA.

Dr Shilpa Mehta, in charge of foster care at Jatan, says the new concept is tough even for prospective foster couples to understand. "Under foster care, couples are not a child's parents; they are not even legal guardians. They are just temporary caretakers," she says.

But keeping children in a family environment - even if for a short while - is better than keeping them in institutions long term, says Ian Anand Forber Pratt, himself an adoptee, who founded Foster Care India, the country's first foster care non-profit begun in Udaipur in 2012.

"Even the best institution can offer a child only good food, protection and education. Compare that with what a family can give: personalised care, a sense of attachment, a sense of responsibility and childhood memories. Institutions tend to isolate children from the natural environment by keeping them bound by routine. However, we have all children," says Pratt.

Back in Savina, Bhagwatilal says, "I do not think long term. We will do everything for him as long as he is with us - be it for just one more day or forever."

Avantika does not sound as pragmatic. "She is mine," the mother says, authoritatively, as she tries to rock the child to sleep.

WHAT IS FOSTER CARE

‘Foster care’ means placement of a child, by the child welfare committee for the purpose of alternate care in the domestic

environment of a family, other than the child’s biological family, that has been selected, qualified, approved and supervised for providing such care

WHO CAN BE FOSTER PARENTS

- Both spouses must be Indian citizens

- Both of them must be willing to foster the same child

- Both spouses must be above the age of 35 years and must be in good physical, emotional and mental health

- Ordinarily should have an income in which they are able to meet the needs of the child

- Both spouses are medically fit

- Should have adequate space and basic facilities

- Should be willing to follow rules laid down including regular visits to doctors, maintenance of child health and their records

- Should be willing to attend foster care orientation programmes

- Must be without criminal conviction or indictment

- Should have supportive community ties with friends and neighbours