|

|

|

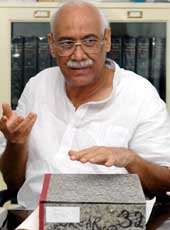

| Pure magic: (From top) B.N. Uniyal; the Sorcar letters; and a poster of one of the great magician’s shows (Pix: Prem Singh) |

On May 18, two legacies were handed down. One of them got caught in media flashbulbs while the other arrived in a nondescript cardboard box.

It was the day on which national dailies carried the picture of P.C. Sorcar Junior, the magician, handing over the family inheritance of magic to his eldest daughter Maneka. It was also the day, B.N. Uniyal, former journalist and rare book collector, received the Bloomsbury package he was waiting for.

P.C. Sorcar Senior himself might have been able to conjure up goldfish, pink ribbons or grey rabbits from that box but those weren’t what Uniyal was fishing for. The box, instead, contained the senior Sorcar’s correspondence with his English bookseller, George Jenness, from the 1950s, his own album of press clippings, first editions of Sorcar’s books, brochures and programmes of his shows and even advertising posters of magic shows from those years. All this and more for a neat sum of £160.

As Uniyal holds up a brilliant blue “Gilly Gilly Gilly Gilly Phoo…” poster advertising the bizarre claims of Gogia Pasha, he says, “I am not a magic book collector but I was intrigued because I had never seen a Hindu magic book.” Also, Sorcar Sr, according to Uniyal, was one of three Indians who showcased India overseas as a country not just of beggars and snake charmers in the early post-independence period. “Gama Pahalwan, the wrestler, Mir Sultan Khan, the chess player, and Sorcar were the three men who did more for India’s image outside than anyone else,” Uniyal stresses.

The 1950s ushered in a golden period for Sorcar Sr in India and abroad. After years of anointing himself as “Sorcar, the world’s greatest magician,” the world also seemed to acquiesce to the extended surname. It was during this time that Sorcar Sr struck up a professional and sporadically personal relationship with Jenness, a bookseller, specialising in magic books and paraphernalia, from Enfield, Middlesex. Jenness kept all those documents carefully and neatly labelled.

The handwritten correspondence between Sorcar and Jenness is more than just an order and receipt of books. Midway between the two decades of correspondence, Sorcar’s address of Jenness slips from “Dear Mr Jenness” to “My dear friend Jenness”. Sorcar Sr’s letters seem to indicate that Jenness was not only his book source but also an advisor on the latest goings-on in the world of magic and an advertiser of his skills. Jenness also sold Sorcar Sr’s books — though he periodically urged the conjuror not to unilaterally send him a consignment of his own books for sale unless specifically asked to.

One of the earliest letters, dating back to 1951, has Sorcar Sr asking Jenness for books on stage illusions, luminous paint effect, stage craft and scenic effects. Through the years, the letters request Jenness to search and source not only books on magic but also playbills, brochures, programmes, press reviews of other magicians, posters and even scrapbooks of his competitors. While touring in Japan, Sorcar Sr also wrote to request for books on silk magic and blindfold methods.

“The letters show that Sorcar was meticulous, diligent and passionate about the pursuit of knowledge. He constantly updated himself with new developments and innovations the world over,” Uniyal says.

Sorcar Sr’s return addresses on the letters indicate that no matter where he was — Wellington, Tokyo or Cairo — he was always in touch with his bookseller. “He was also a big self-promoter, the sign of a successful man,” Uniyal says smilingly.

The language in the letters does point to some preening in the mirror. For instance, many a time Sorcar Sr refers to himself in the third person. “The Mayor of Wellington gave a great reception to the Great Sorcar,” the illusionist says in one letter. In a 1952 letter, he writes how he toured Bombay, Honk Kong, Penang, Singapore and created new box office records.

“One very great British magician with 10 tonnes of equipment and 30 assistants toured Bombay for four weeks to earn Rs 37,267 in sales,” he writes, pointing out that he earned Rs 2,94,637 for shows in the same duration. He adds that in another week he was richer by Rs 98,796, creating a record in the Singapore box office.

However, after such statements gilded with self-adulation, Sorcar Sr also adds, “Anyway, this letter is not for self-praise.”

But his admiration troupe consisted of more than just himself. In 1956, Sorcar Sr’s tricks caused a flutter of panic in London. Clippings from UK newspapers erroneously mention a “Pakistan magician” who sawed a woman into pieces on stage, which in turn flooded the BBC with calls enquiring about the well being of the poor woman. The BBC, tired of answering the calls, had to dedicate a separate line for the panic calls.

Sorcar Sr knew how to handle not just success but also competition. One episode — spelt out in a brochure in the Sorcar Sr papers — went like this. Kala Nag, a famous German magician of the time, was a good friend of Sorcar Sr But they fell out after a while and a professional battle ensued. To put Sorcar Sr in place, Kala Nag went on a mud-slinging spree claiming that Sorcar Sr stole tricks from others and that he came from “Holy Cow” country.

Sorcar Sr did not take that sitting down. He got Arthur LeRoy, a fellow magician, historian and friend, to write an article, which extolled Sorcar Sr as the greatest magician and ran down Kala Nag. Sorcar Sr went on to use LeRoy’s article as a citation in further articles, blissfully ignoring the fact that LeRoy’s article was published in Sorcar Sr’s own magazine. But all that is fine print because today P.C. Sorcar Sr is still known as one of the greatest magicians ever. And his correspondence and books are sold on Bloomsbury auctions.

Jenness’s last letter to Sorcar Sr dates back to 1971, the year Sorcar Sr died. “It seems that Jenness was not informed of Sorcar’s death by the family,” explains Uniyal. But Jenness, the Englishman that he was, wrote to the family as soon as he found out, expressing his sympathy.

He also informed them about the money he owed Sorcar Sr and requested them not to send more copies of Sorcar Sr’s books as he already had more than he could sell.

The 1971 letter is the last one of the long correspondence, though there are a few stray letters to the book seller from P.C. Sorcar Jr. “I knew Jenness through my father but I didn’t have any connection with him. His name is still on our mailing list though,” says P.C. Sorcar Jr from Calcutta.

In the mailing list, and buried in a certain nondescript box in Uniyal’s office.