Prakash Jha looks a bit scattered. And there's good reason for that. His new film has just been released, and its main star - Priyanka Chopra - is shooting in the US. The director-producer-screenplay writer has to deal with its promotion all by himself, and he appears distracted.

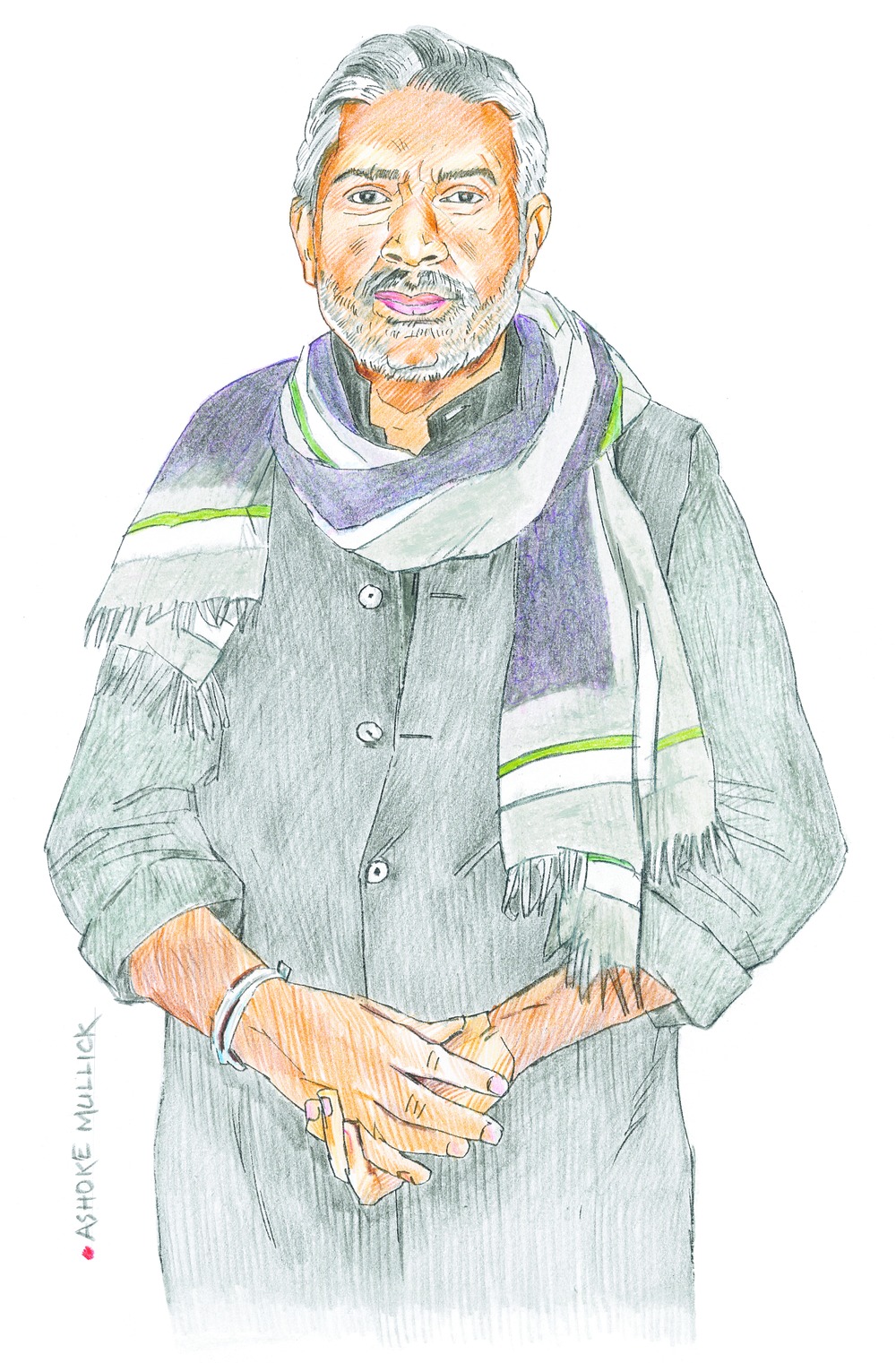

He sits in his office - wearing a grey sweater, teamed with a gamchha-like grey shawl that works like a dupatta, and a pair of blue jeans. The office in Mumbai is charmingly old-world - right from the two benches at the reception to the ancient fan. You have to remove your shoes before you step in for there is a little temple - with a Durga idol flanked by Ganesha and Hanuman - just near the entrance.

Is he jittery about his film being released in such politically polarised times?

"Oh no. My film is not a political film. It is a film about society and police and how the equations work at the grassroots level," he replies. "In the end, it is not politics but the story that matters - whether people connect with it and feel one with it. Or do they feel ambivalent? That anxiety is always there."

His films, as he puts it himself, are different from the "boy meets girl, girl meets boy and they fall in love" genre. "There is always the niggling worry whether it will work because it is not a known story and you have created a story."

Audiences, he explains, go to see "a" film - and not "a political" film. "That it has politics as a subject is incidental. Films should be able to engage - people should be able to relate with it and its characters. And you have to create a drama around it. A film should be worth the money people pay to see it."

But he himself is a political person - having fought (and lost) elections in Bihar. How does he view the political climate in Delhi, where people are out on the streets?

Jha is blasé about it. "India is a churning society and it is an alive society and it is always on the boil." He knows about student movements - which have been central themes in many of his films such as Aarakshan and Satyagraha. Jha, in fact, has always been able to feel the pulse of the students.

"Basically, I take things which are happening around and try to assimilate them. I ask why these things are happening and what are the facts and while working on them, stories emerge, characters emerge and the narrative emerges. It is my way of communicating. I don't get personally involved. I am happy in all situations."

For the first time, Bollywood seems as polarised as the rest of the country, with people standing up against the Narendra Modi-led government, or speaking out in its favour. "Perhaps it was always there within them," he reasons. "But now it is very evident. Opinions are coming out and they are talking about issues." Jha, however, is quick to add that having political differences doesn't mean that artistes do not work with people they don't share their ideology with.

Film watchers are apprehensive about Jai Gangaajal, mainly because his 2003 film Gangaajal is considered by many as one of his finest works. Indeed, it was a landmark film that captured, without appearing like a documentary, relations between the police, politics and society in rural India. Can Jai Gangaajal, coming 13 years after the first film, hold a torch to it?

" Jai Gangaajal is a different story, has a different angle and is in a different time. Both the films are about society and police relations. They have the same soul, but everything else is different: the characters are different, the take-off is different, the situation is different. That was on the Bhagalpur blinding case, this is on something else."

The protagonist in the earlier film was Ajay Devgn, who has been replaced in the new film by Chopra, who plays the role of a woman cop who is posted in a particular district since she is considered weak because of her gender. Manav Kaul is the villain. And the director plays the role of Bhola Nath Singh, a cop whose life takes a 90-degree turn. By becoming a character, Jha believes that he is now "even more a part" of Jai Gangaajal.

How did the director decide to become an actor? "One has to work out the technicalities, but in principle it is exciting. It is one more facet of your personality. You think, you write and you perform. I am always looking for new challenges and some excitement - and that is how this came about."

His new film is also being talked about because of Chopra, who is now shooting for the hit US television series Quantico, and is arguably the topmost actress in Bollywood today. "Since we (Prakash Jha Productions) prepare well, we shot all her sequences in 27 days when she had a gap between Bajirao Mastani and Quantico. She couldn't believe it. She did the dubbing when she came here for Christmas."

Jha is happy with Chopra, who he believes was able to get into her character well. "I work with actresses long before the actual filming starts. Priyanka has also matured. She creates her own personality." Then, as an aside, he adds, "Khaki mein waise bhi logon ki chaal badal jaati hain" - people start behaving differently in khaki.

He himself is fascinated by khaki - which explains why the police force is presented with its strengths and weaknesses in his films.

"I try to look at the police force from their point of view: the grey, the blue, the blacks. Some of them are fantastic but are not able to perform. When I try to build a story, the police automatically become a part of my story. The police are there in the story because I am dealing with a small-town society where there are law and order issues."

And he knows about law and order issues because Jha is from Bihar - having grown up in Champaran. Not surprisingly, the Badlands of Bihar are his favourite background. "I always feel that Bihar is to India what India is to the rest of the world. Look at it and think about it. India is full of ideas, intelligence and also a whole lot of anomalies. Bihar is the same."

The state has seen its share of agitations, he points out. In fact, most agitations - including the one led by Jayaprakash Narayan - have originated in Bihar, he adds. But the state, he holds, has changed under Nitish Kumar ji. "There are more schools, there is electrification. Women have a role to play," he says. "I never became an MP, so I could not be in a position where I could legitimately draw some resources for the people and their development." But he runs a non-government organisation which does "a lot of work" there, he adds.

Politics' loss is cinema's gain, as Jha is now completely immersed in celluloid. For Jai Gangaajal, he rewrote his script 16 times. He writes his scripts in his office in Mumbai or in Patna, where he has a house. Sometimes for the basic draft, he needs isolation. And then there are times when he wants to go out and play squash, work out and go for long walks. He does weights, yoga and circuit training. "I also like to eat well but I have a strict regimen. I sleep at 10 and wake up at five."

Jha, 64, has directed over 25 films, including some documentaries. He shot into fame in 1984 with Damul, which focused on bonded labour, caste politics and migration. It won him a National Award, as did many of his later films, including Apaharan and Gangaajal. His debut feature film was Hip Hip Hurray, also released in 1984.

The film starred Deepti Naval, to whom he was once married. No, he says, he has no more time for love. "I get sucked into my work. Work is amazing. So engaging and compelling. Where is the time to indulge in all this," he says, making a wry face.

He is also firm about not giving out a message through his movies. "I don't try to do this. I just tell a good story. The message, if any, has to emerge automatically through actions and dialogue. It has to be organic. But the message is not my starting point, it is not my middle point and it is not my end point." Curiously, though, it never leaves you.