|

.jpg) |

.jpg) |

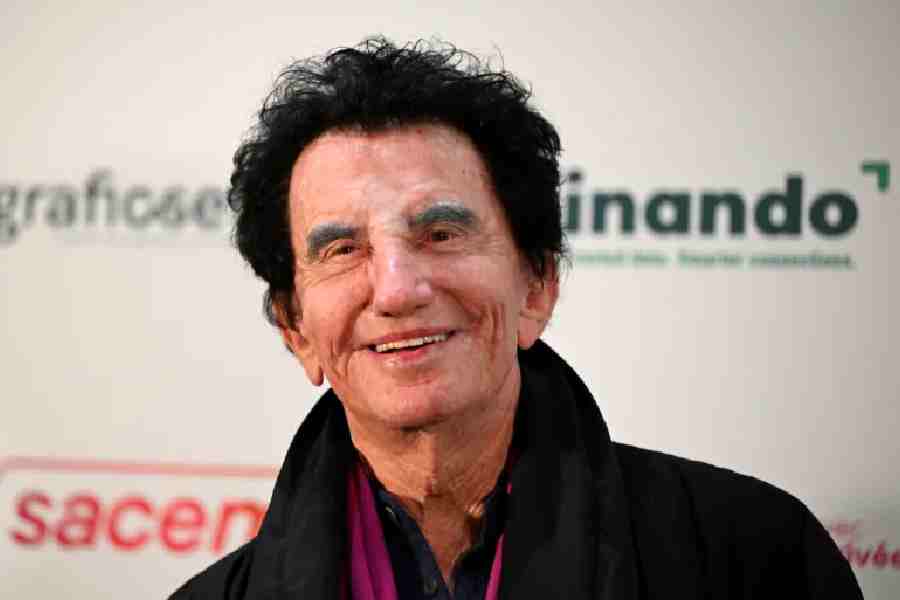

| DREAM-TURNED-NIGHTMARE: (From top) Pardeep Singh with his mother; the visa of one of the men; and Narinder Singh at work in Al Najaf Lying on a charpoy in his courtyard a year ago, Tahil Singh had imagined a fancy life abroad. He is back on his string cot, but does not dream anymore. Instead, Tahil, 21, gets nightmares about a time he’d rather forget — seven months spent in war-ravaged Iraq. |

“I wake up at night thinking I am sleeping in a bunker in Iraq,” says Tahil. He had thought he was joining the US Army. But after working in a hotel, supermarket, packaging company and construction group in Iraq, Tahil came back to India on August 29, without earning anything.

He is one of 28 men, mostly from Punjab, who managed to return after approaching the Indian embassy in Baghdad for help. The youths were taken to Iraq last year by travel agents who promised them jobs as carpenters, cooks, drivers and masons in US Army camps in Iraq. They were told they would earn US $600 (Rs 28,000) a month, with free food, stay and medical facilities.

“I knew there was risk to life in Iraq,” says Gurminder Singh, 28. “But I thought if I worked well in the army camp, I could go to the US one day,” says the mason, now known in his village in Hoshiarpur as Iraqwallah Gurminder or Gurminder of Iraq.

The US embassy in Delhi stresses that the US Army does not place job advertisements in India for support staff in Iraq. But the men realised they had been duped only when they reached Iraq. “There were no US Army jobs for us,” says Tahil. Instead, he adds, they worked as bonded labourers for 18 hours a day without pay in private companies. “We got nothing to eat except flatbread and rice once a day,” alleges Tahil, now back in Umarpur village in Hoshiarpur.

With 4.8 lakh unemployed youth in Punjab, thousands have been illegally leaving the country for a better life abroad, often with the help of unscrupulous agents. Iraq is the latest destination. The jobseekers say they paid around Rs 1,40,000-2,00,000 to agents for work in Iraq.

“My knowledge of Iraq was limited to Saddam Hussein’s execution and the US invasion,” says Pardeep Singh of Hajipur, Hoshiarpur. “I was apprehensive to begin with, but lost my fear when the agent said the US camps had high security.”

The workers believe they were given visas, but an Iraq embassy official, speaking confidentially, says the embassy does not issue work visas to Indians, except in special cases. Emergency 10-day visas are given on arrival when people enter through other countries. The workers, however, stayed on in Iraq well past the visa expiry. “I didn’t even know my visa was for 10 days,” says Gurminder.

With three pairs of clothes in his bag, he was in a group that left for Jordan in June, and was then taken to Erbil, 300km from Baghdad. “When we landed there, we expected a US Army vehicle to pick us up. We waited and waited, and then realised we had been trapped,” he says.

Finally, an Iraqi who claimed he was their agent’s counterpart approached them. “He took away our passports and then pushed us into a small truck,” recalls Gurminder, who was taken to Al Najaf, 160km south of Baghdad, to work in a construction firm.

The men relate tales of torture. “The security guards threatened to shoot us with their AK-47s if we boycotted work,” says Pardeep. “Strapping Iraqi men in boots kicked us when we asked for food or water,” adds Narinder Singh, 26, of Dhirpur village in Jalandhar. Narinder says he was forced to clear fields strewn with used missiles and bomb shells. “I had to run a tractor on land with live shells to make it arable.”

The horror stories don’t end here. Tahil, a Sikh, was forced by his employers to cut his hair. “I felt like ending my life then,” he says.

The labourers, who lived inside walled compounds outside cities, started talking among themselves on how to break free. Pardeep, one of the few who’d been paid a part of his salary, says he bribed his Iraqi agent — giving her his savings of Rs 27,000. “She dropped us to a deserted area in Baghdad at midnight and gave back our passports. Then we took a taxi to the Indian embassy.”

Others realised they would have to fight with their employers and escape. “We managed to snatch our passports. The guards threatened to shoot us. But we told them we were already dead inside, how could they kill us,” says Narinder. The group then boarded a bus to Baghdad and reached the embassy.

The embassy was of not much help either. “They said it was not the government’s responsibility to send us back,” alleges Narinder. So he wrote to his father in Dhirpur, who lodged a police complaint, borrowed Rs 30,000 and sent him a ticket.

An external affairs ministry official states the government provides tickets to Indians in distress if they return the money later. “Every year, 11 million Indians travel abroad; it’s not possible to provide tickets to everyone,” he says. But in an official reply to the Punjab High Court, which is hearing a petition on the issue, the ministry says it is facilitating the return of men still stranded there.

Meanwhile, eight FIRs have been lodged in Punjab and two agents arrested.

“At times, complainants reach a compromise with the agents to get their money back,” says inspector general of police V.K. Bhawra. “That weakens the investigation.”

The police say it is difficult to build a case against agents because payments are made in cash. “Money is also paid to sub-agents at different places at different times,” adds Rajeshwar Singh Siddhu, superintendent of police, Hoshiarpur.

The agents claim they did no wrong. “We had sent men after seeing newspaper advertisements for jobs in US Army camps. How would we know these were false,” asks J.P. Benwal of JM Overseas, a Chandigarh-based travel agency.

Now that the case is in the high court — which has issued notices to government departments —Tahil and the others hope they’ll get their money back. But it will be a while before he starts to dream again.