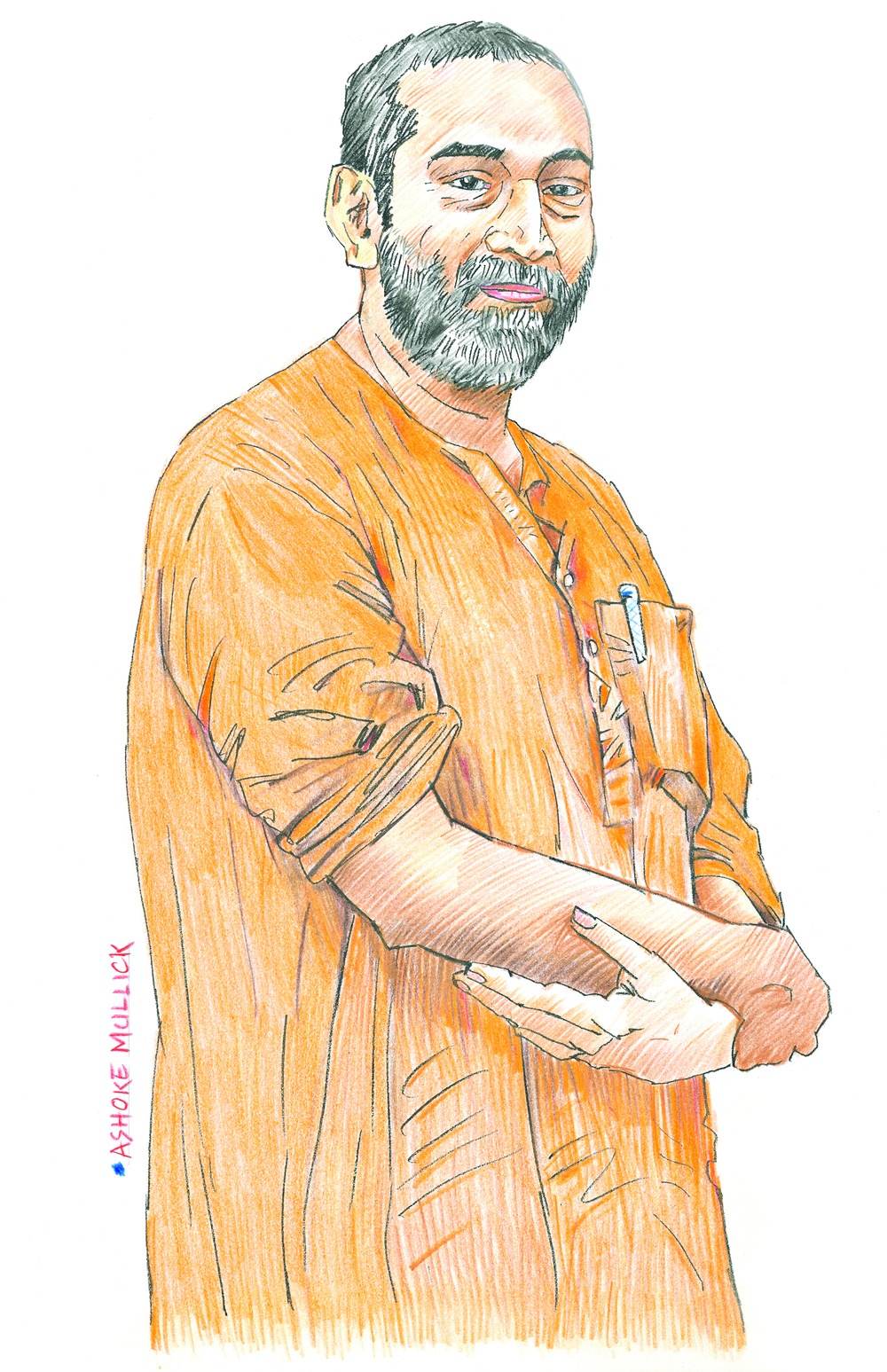

Let's not try to define Mahan Maharaj. Let's just state the facts. He is a mathematician. He is a monk. He is in Delhi to receive the coveted Infosys Prize for mathematical sciences for 2015. He has been put up at the Taj Palace Hotel. And, right now, he's standing outside, smoking a quick cigarette.

I have been chasing him for a while. But the professor of mathematics is reluctant to meet the press. "I am not comfortable talking to the media. They want to write about me more than about my mathematics," he'd told me earlier.

So I quickly follow him out, hoping to catch a few words before we start talking earnestly about maths. How does he feel about the latest recognition that has come his way from the Infosys Science Foundation? Pat comes the reply: "I am happy that maths is getting recognised."

This is going to be a tough one. I mean, how much mathematics can a reader take? I have already been urged not to ask him about his days at the Belur Math, where he spent more than a decade studying and teaching mathematics at the Ramakrishna Mission Vivekananda University.

Maharaj, who did his postgraduation in mathematics from the Indian Institute of Technology (IIT), Kanpur, and then a doctorate from the University of California, Berkeley, first grabbed attention when, in 2011, he won the coveted S.S. Bhatnagar Prize for Indian scientists below the age of 45. He is currently a professor at the Mumbai-based Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), and takes courses at IIT, Bombay.

He has had his smoke, and we settle down in the lobby. Maharaj, 47, stands out in his orange robes in the glitzy hotel foyer, but he is not troubled. I dutifully start with maths. What made him change subjects midway when he was studying at IIT, Kanpur? When he dropped out of the BTech electrical engineering course and opted for mathematics, many people - including his parents - were surprised.

"I do not know whether I should put this on record. I did poorly in exams and I realised that what I wanted to do was mathematics and not engineering," he says. His parents were obviously worried when they received a long letter from their son explaining his reasons for going in for maths. His father, who was a manager with a Calcutta firm, wanted him to give the move serious thought.

"My father, who has a background in law, asked me to come to Calcutta and said I could send the application for changing my course after a thorough discussion. I, instead, sought his permission for giving the application first. I promised that I would take it back if they could convince me. A law point for a law point," he chuckles.

Neither side was convinced of the other's argument, and the stand-off continued briefly. "Subsequently they gave in as they realised my romance for the subject was real."

Maharaj works in the area of geometric topology, an emerging area in mathematical research. "When I returned to India, the number of people working in this field was in single digits," he says. There too, he specialises in hyperbolic geometry. The most visual example of hyperbolic geometry is a tree. A tree has a stem, which branches off and these branches then branch off further and so on. Even if you carefully look at a leaf, you would see a central vein bifurcating to smaller veins, which again branch off. Another example of this is the surface of the human brain.

He is concerned about the current state of mathematics education in Indian universities. The curriculum, particularly at the undergraduate level, promotes only rote learning, he believes. "Whatever creative edge that the students have is systematically blunted by this very dated educational system," he says.

Teaching, he rues, has been converted to a 9-to-5 job. When a teacher chooses a course, he or she will continue to teach the same course for the next 20 years, he points out. To these people, the subject is not going to be a "living" one. "Teaching a dead subject is only going to cause the death of brain cells," he holds.

In India, he argues, mathematics is taught in a "prehistoric" way. "Why? Because we love to be lazy," he says.

Not all is gloomy, though. Some institutes, such as the IITs, the Chennai Mathematical Institute or the Indian Institutes of Science Education and Research are exceptions. A few central universities such as the universities of Delhi, Hyderabad and Punjab are modernising their maths curriculum to an extent.

"But a lot more needs to be done," he says.

He knows that, for a major part of his education was in India. Maharaj - born Mahan Mitra - grew up in Calcutta, where he studied at St. Xavier's Collegiate School. While doing his master's in Kanpur, he developed an interest in the teachings of Swami Vivekananda - a passion that followed him to Berkeley.

It was while at Berkeley that he decided to become a monk. He had said in an earlier interview that he was "quite strongly atheistic" when he was in college. But what drew him to a monastic way of life was the focus on fundamental values such as truth and unselfishness. "For me, strictly personally, the monastic way of life provides a lifestyle where it is easier to act on the basis of these values on a day-to-day basis," he had said.

After completion of his PhD, he came back to India to join the Ramakrishna Mission in 1998 and became a monk in 2008. He visits the mutt occasionally. Does he go to Calcutta to meet his family? "Since I have taken the monastic life, please don't ask me about my family," he replies.

What interests him outside the realm of mathematics? "I love to listen to Hindustani classical music. In fact, classical music is very similar to mathematics," he observes. Among the Hindustani ragas, Yaman and Kedar are his favourites. "Yaman calms me down," he says.

Does he need calming down, I probe. "Not angry, but I get annoyed sometimes," he answers. "My pet peeve is a mathematical textbook which has been around for more than a century." The book, The Elements of Statics and Dynamics by British mathematician Sydney Luxton Loney, came out in the early 20th century and is followed in a large number of Indian universities even today.

Perhaps this was a good book at some point of time, but it's not stimulating anymore, he believes. More often than not, question papers (at undergraduate levels) recycle the same problems from the book. So all that a student has to do is study them by heart.

''This is not the way to teach or learn mathematics," he stresses. "At a larger level in our education system, asking questions is somehow not encouraged. Even at the social level, if you ask a question or two, people get insulted. Asking questions probably exposes some kind of a lacuna, so people take it personally. They don't realise this attitude actually hampers the very crucial aspect of being a human being," he explains.

Questions, he believes, have to be asked. "When one question is asked, it gives rise to 10 questions to which we do not know answers. Choosing the right research question and finding answers to it is what pushes human knowledge. The people who ask the right questions inevitably make some progress. That system is yet to come here," he says.

Innovative thinking, he maintains, is the way to research. "Rigid minds, which are incapable of thinking afresh, cannot push for academic excellence. If that is the mindset then one is up against a wall."

Maharaj yearns to bring about a change in the way maths is taught in colleges. Together with Rajesh Gopakumar, a theoretical physicist at the International Centre for Theoretical Sciences at Bangalore (part of TIFR), who was his friend from schooldays and at IIT, Kanpur, and two of Maharaj's students, he is setting up a Fundamental Science Education Trust in Mumbai. The trust will try to push for innovative ideas in education, particularly in maths. "The entire Infosys prize money [Rs 65 lakh] will be donated to the trust," he says.

Taking him away from the world of mathematics is tough. I tentatively ask him if he likes to read books and watch films. "Yes, I do, but my clock stopped some 30 years ago," he replies. "Even today, I love reading Rabindranath Tagore in Bengali. I loved watching films made by Satyajit Raj and Ritwik Ghatak. Among the new generation directors, I used to like Rituparno Ghosh's works." Among the English movies his all-time favourite is Becket, a 1964 film starring Richard Burton and Peter O'Toole that he's seen 20 times.

We are about to wind up when his cell phone crackles to life with a melodious male voice. "That's Bhimsen Joshi in raag Kedar for you," Maharaj says of the ringtone.

Another time, I must ask him about music and maths.