The year was 2005. It was just another work evening at the newsroom of Greater Kashmir (GK), the largest circulated English language daily of the Valley. Some people had been killed in the Valley and the news was slotted for the "briefs" section. The lead story that day was a report on the hangul, the musk deer native to Kashmiri forests, facing extinction. Malik Sajad, then a precocious 18-year-old GK cartoonist, was looking for inspiration.

That day, Sajad drew the Kashmiri and the hangul in a single frame and captioned it "Endangered Species".

The striking cartoon appeared on the newspaper's front page. It also became the basis of Munnu: A Boy from Kashmir, an autobiographical graphic novel by Sajad, published 10 years later. A reclusive young man of charming manner, though a little weary of his 29 years, Sajad was in Calcutta recently to talk about the writing of Munnu at the comics festival in Jadavpur University (JU).

Sajad is the eponymous Munnu, the name his family gave him because he was the youngest. In Sajad's novel all Kashmiris are depicted as hanguls, endangered; the remaining humans are humans. "I had stories to tell. I had to figure out how to tell them," said Sajad; it didn't come easy.

The hangul is an effective visual metaphor. It suggests that the violence committed in Kashmir is of the sort inflicted by humans on creatures no longer deemed human. The device also helps the writer distance himself from what is an intense personal story, viscerally told.

Munnu is the youngest of five siblings growing up in a 1990s Srinagar neighbourhood where AK-47s are more readily available than paintbrushes. He is in junior school when he starts carving AK-47s out of erasers and earns quite a fan following among schoolmates. Munnu is a bildungsroman, the story of a boy who grows up to become Sajad, the artist, despite everything.

The first chapter is titled "Family Photo"; the opening image, a group photograph of Munnu and his siblings - Bilal, the eldest brother and Shahnaz, the only sister, are standing, and in front of them, sitting in a row are Munnu, Akhtar and Adil.

It is 1993, Eid. Munnu's father is an artisan who creates intricate designs on blocks of walnut wood. The family lives in Batmaloo amidst a people who want an independent Kashmir and are fighting for it. Munnu's parents fervently hope that their children will not grow up to become militants.

That day, after the ritual Eid photograph in the neighbourhood studio, the siblings walk back home together only to be shouted at by their mother. "What if the mother of a 'martyr' sees all of you brothers walking together like a cricket team?" she screams. "You want to rub salt on her wounds?"

Sajad draws a picture of Kashmir that is rarely seen: of its everyday life, detailed in its contours of hardship and suffering, but also of its beauty and love. "Most people see Kashmir through news, Bollywood or when something happens," Sajad told the audience at JU, "When you summarise Kashmir in terms of a story you miss out a lot."

Munnu perfects his own art from years of keenly, obsessively, watching his father at work, etching the traditional chinar and paisley motifs. By the time he finishes school, he is already a political cartoonist working for an Urdu newspaper.

Sajad took two years to write Munnu, which is also about writing Munnu. Part of the book was also written abroad; once, in New York, he took four days to write out a single line: "That year spring arrived early." (The line is to be found in the chapter "Paisley", which is also the name of an American artist Munnu falls in love with.)

Sajad's other struggle was portraying Kashmir's history. "I don't know history or politics," said the artist who went on to study visual arts at Goldsmiths, University of London. Telling Kashmir's history was particularly troublesome because the way it has been told traditionally is extremely inadequate, Sajad stressed.

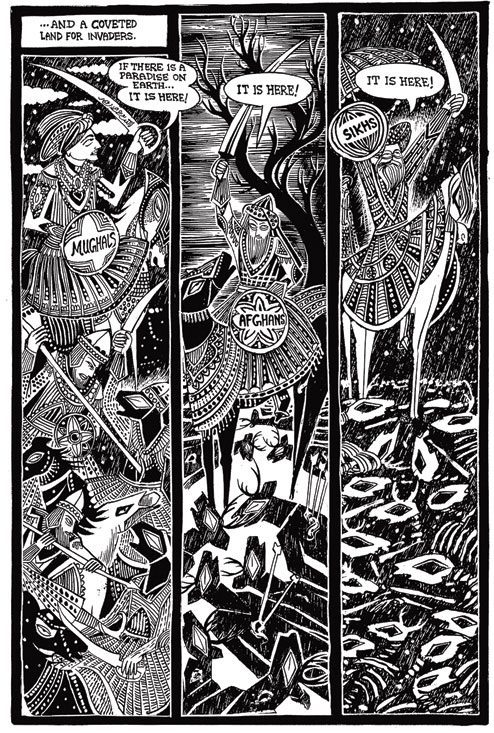

So in a stunning chapter, towards the end of the book, a collage of the various episodes of Kashmir's history comes together, from the times before Kashyap Rishi through the Buddhist era, the Mughal period, the British and the Dogra reign, to the present day.

The personal narrative is suspended. The visual style shows striking departures, too. The Mughal period, for example, is drawn in the miniature style, quite a contrast to Sajad's otherwise minimalist style.

"The chapter on history was necessary, in the interest of the story," said Sajad.

But it may strike some as an angry outburst, a hectic juxtaposition of images aimed at those who require that every book from the subcontinent should explain its immediate historical context to the (English-speaking) world. The chapter is titled "Footnotes".

Anger bubbles through rest of the book as well. It is there in the sharp, jagged edges of the hangul figures. It brews under the tense dialogues, erupts in the casual way armymen grope young Kashmiri boys, and culminates in a sudden, frightening end.

And what about the great resemblance between Maus, the graphic fiction classic by Art Spiegelman, and Munnu? They look like mirror images. Both are graphic novels, both talk about human tragedies, both use animal figures - Maus is about the Holocaust, where the Jews are portrayed as mice and the Nazis as cats. Even the visual delivery of the two novels is similar; both contain black and white drawings against a detailed background. Maus was completed in 1991; and Sajad said he did not read it till after 2010.

He spoke admiringly of other graphic novels such as Persepolis, but said he had derived inspiration for his book from the image of the hangul. Otherwise, he was influenced primarily by literature and cinema. He said he was devoted to Manto, admired Gunter Grass and Umberto Eco, and claimed to love Tarkovsky and Satyajit Ray - "who does not try to capture everything".

Sajad said he thought of himself as a cartoonist - a rather old-world description - rather than as a graphic novelist. The word cartoonist is part of his email ID.

One's story - and one's signature - must be one's own.