We've got it wrong about Ashok Khemka. The man of many transfers was not shifted out of his office for the 46th time as reported in the media. "It was actually for the 48th or 49th time," the bureaucrat says nonchalantly.

Khemka, 49, is now as far removed from a hotspot as can be. He is no longer probing the land deals of Robert Vadra, Congress president Sonia Gandhi's son-in-law, exposing a seed purchase scam which led to a probe by the Central Bureau of Investigation (CBI) or unearthing corruption in Haryana's transport corporation. Instead, he is a secretary and director-general in the department of archaeology and museums in the government of Haryana.

The 1991 batch Indian Administrative Service (IAS) officer admits that there isn't much to do now. "It's been little over a week. I sit alone in my office most of the time. I don't even have any staff except for an assistant," he says.

Sure, he agrees, bureaucrats are not holy cows who cannot be transferred. "But I am concerned with the reasons behind the transfer," he says. "I unearth a scam or am in the middle of something important and I get transferred."

It's a complaint that you hear from IAS officers across India. Take the case of M.N. Vijaykumar, who was transferred 27 times in 32 years of service. Currently an officer on special duty and principal secretary in the department of personnel and administrative reforms in the Karnataka government, Vijaykumar, 59, believes that the highest price for his uprightness was paid by his mother with her life when he was transferred six times in nine months from September 2006 to June 2007.

A patient of hypertension, her health deteriorated after she came to know of attempts on her son's life followed by a puzzling transfer to Belgaum, 500km from Bangalore, to an office that didn't require an IAS officer of his rank. She died in August 2007.

A 2010 survey of the officers of the central civil services revealed that 34 per cent of the respondents considered resigning from the civil services at some point in time.

What worried an honest government servant was the prospect of being posted to an obscure spot with "zero job content or worse a string of such postings as a price for one's honesty and commitment", the survey said.

Haryana, Uttar Pradesh, Bihar and Tamil Nadu, bureaucrats say, have the worst records when it comes to transfers.

"We used to get very agitated, but now we are just sick and tired of the whole thing," laments senior IAS officer Sanjay R. Bhoosreddy, secretary of the 4,500-member Central IAS Association.

It is the people of India who are the ultimate losers when officers are transferred in quick succession, Bhoosreddy points out. "There will be no sense of continuity and work definitely suffers. Psychologically, officers also feel uprooted," he adds.

What irks honest babus is that there are always corrupt bureaucrats who can take over when an officer is transferred. "So transfers effectively achieve the purpose of covering up corruption," says Arun Bhatia, a retired IAS officer of the Maharashtra cadre.

Bhatia, who had a total of 24 transfers in 24 years, believes that transfers before the completion of a term of two or three years are "usually vindictive, arbitrary and corrupt".

The case of U. Sagayam is an example of that. The Tamil Nadu IAS officer was transferred out of Madurai in 2012 as soon as he unearthed a mining scam involving the local mafia and politicians. Sagayam has been transferred some 20 times in 23 years.

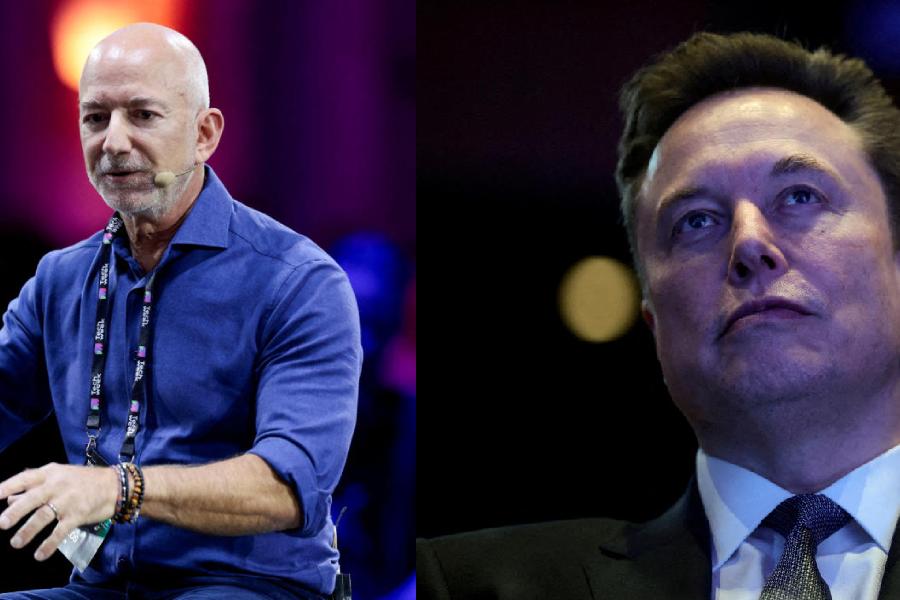

(From top) Ashok Khemka,

U. Sagayam and Arun Bhatia

The local people admired him for removing encroachments, improving the bus stand and opening a farmers' food court to promote traditional dishes in Madurai. But his bosses wanted him out. Currently posted as the vice-chairman of Science City in Chennai, he was also appointed by the Madras High Court as a legal officer to probe granite mining irregularities in the Madurai region.

"I like my work to speak for itself," is all that Sagayam would like to say.

The problem, insiders hold, is that not all politicians - or even senior officers - want honest bureaucrats. A stickler for rules, for instance, may come in the way of a lucrative deal from which a politician, or even an officer, expects to benefit.

"One has to be either corrupt or stay away and let things be the way they are to survive in the system," says an upright officer who had more than 10 postings in the last seven years in Andhra Pradesh. "Taking on the corrupt means you are inviting trouble. You can win the hearts of the people, but you are alone out there and the system gangs up against you," the official, who wouldn't like to be named, rues.

Bhatia knows that feeling. "The entire bureaucracy unites against men like us," he says. "We are looked upon as being incompetent, disloyal, incapable of working in a team, publicity seekers and so on."

Last year, the Supreme Court ruled that those belonging to the IAS, Indian Police Service and Indian Forest Service should spend at least two years in one post. The court also recommended that a transfer could take place before two years only if the civil services board (CSB) in the state recommended it or the government had strong reasons for it.

The court's ruling was in response to a public interest litigation moved by 83 retired bureaucrats, including T.S.R. Subramanian, former Union Cabinet secretary. "There is moral degradation at every level. And bureaucrats have become willing tools in the hands of political masters," Subramanian says.

While some states have set up CSBs, not all the bodies are seen to be fair. A central government official says the boards consist of people who are about to retire, or the "yes men" of politicians. "They are not at all independent," the official contends.

Subramanian stresses that the root of corruption was identified way back in the Sixties by the Committee on Prevention of Corruption - popularly known as the Santhanam Committee, set up under the Tamil Nadu politician K. Santhanam.

The committee identified greed for power and money and a general decline in moral values as the root causes of corruption, and suggested bodies such as the CBI and the vigilance commission to deal with graft.

But even now, after 350 committee reports on administrative reforms, India is yet to evolve a system to protect honest officials and punish the dishonest.

"We are caught in a cycle," says Subramanian, who averaged one transfer a year when he was a bureaucrat in Uttar Pradesh. "Chief ministers are scared of their own MLAs. MLAs are controlled by vested interests at the local level, and they in turn want weak and corrupt officials."

For honest politicians, clearly, a packed bag is the only solution. Khemka, originally from Calcutta, recalls Rabindranath Tagore's popular song when he goes through a difficult phase. Ekla chalo re - walk alone, he hums to himself.

No, Minister!

Officers’ story

Ashok Khemka, 49

Haryana cadre (1991)

49 transfers in 24 years

Unearthed illegal land deals, exposed scams in public supplies and transport

departments.

M.N. Vijaykumar, 59

Karnataka cadre (1981)

27 transfers in 32 years

The first IAS officer in Karnataka to declare his assets, he exposed corruption in the energy, home, and industry departments of the state.

U. Sagayam, 53

Tamil Nadu cadre (2001)

20 transfers in 23 years

Improved infrastructure in Madurai and Namakkal

districts where he was a

collector.

Poonam Malakondiah, 51

Andhra Pradesh cadre (1988 batch)

26 transfers in 24 years

Battled lobbies in civil supplies. Made public health and education departments more transparent.

Mugdha Sinha, 40

Rajasthan cadre (1999)

13 transfers in 15 years

Unpopular among politicians and local people with vested interests.