Close to eight decades ago, a series of panels painted by Nandalal Bose for decorating the venue of the 1938 Congress session in Haripura, Gujarat, prompted the artist to bring the ordinary people, peasants and artisans visiting the sessions face-to-face with themselves in their painted representations. Today, the National Gallery of Modern Art (NGMA) in New Delhi is bringing a new computer-savvy, android-toting generation face-to-face with their fast vanishing heritage.

On June 30, 2016, the day NGMA director Rajeev Lochan retired, the gallery mounted a major exhibition from its collection titled "Rediscovering Haripura Posters: Nandalal Bose". The exhibition spread across two wings of Jaipur House in New Delhi showcases 77 paintings by Nandalal (1882-1966), which were used to decorate the ornamental gates and pavilions of the township that sprang up at Haripura, near Bardoli in Gujarat, for the Indian National Congress session.

Nandalal was invited by Rabindranath Tagore to join Kala Bhavana, which is a part of Visva-Bharati, in Santiniketan in 1920. In 1922, he became the adhyaksha (principal) of Kala Bhavana.

An added point of attraction to this show is the ante-chamber and room devoted to 13 reproductions of Nandalal's illustrations embellishing the pages of the Constitution of India, a facsimile edition of which is also on view.

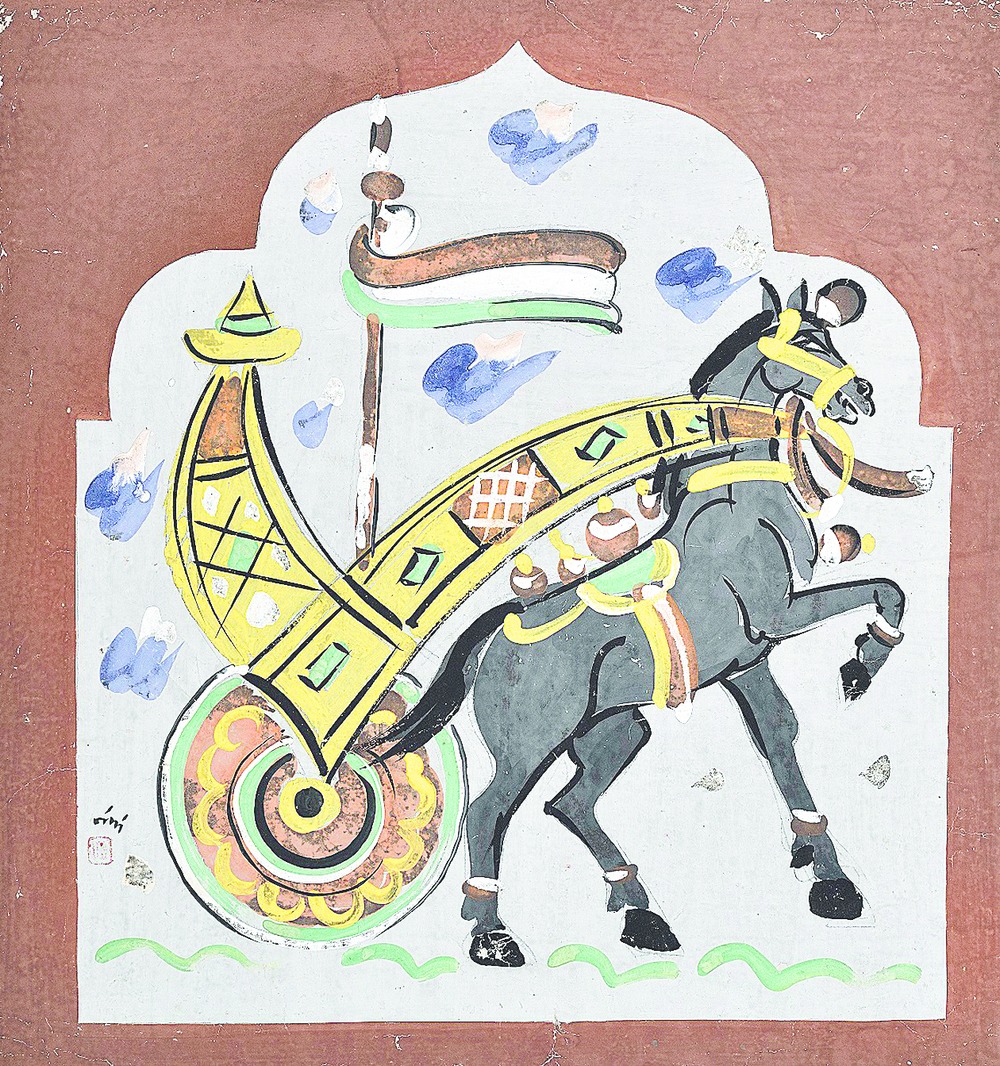

The panels, popularly known as Haripura Posters, were meant to be used as wall-insets for the gates and pavilions. They are painted on paper pasted on cheap strawboard with bright earth colours. The majority of the paintings in the NGMA collection show ordinary men and women, labourers, artisans like the blacksmith and the paper maker, and musicians such as a shehnai player, rudra veena player, drummer and many more. Then there are those engaged in typical rural professions like the dom warrior, a member of the militia from the lowly castes that the feudal chiefs in Bengal maintained, women engaged in normal household activities such as cooking, pounding rice, feeding an infant. There is a gardener, an elderly tailor with a comfortable paunch, a dhobi with his donkey and bundles of washed clothes. Some of these activities are fast becoming obsolete like that of the dhunai, the man who cards cotton wool to stuff quilts and mattresses.

There are a few bird and animal forms which are treated in a playful, decorative manner but still retain their basic characteristic like the peacock, the lion and the fox, a few floral forms that evoke the grace and beauty of Japanese floral studies and some ornamental forms. The exhibits at NGMA carry Nandalal's calligraphic signature "Nanda" and a tiny square red seal.

The paintings show joyous buoyancy and pulsate with the rhythm of life. With a few strong brushstrokes, the subjects are rendered with great vivacity. The brushwork is fluid and spontaneous. The colours are limited in range - Indian red, yellow, green, greyish blue, vermilion, orange, black and white - but their application is rich and saturated. Early on in his life, Nandalal was known to have toyed with the Kalighat painting style. In the Haripura Posters, he had once again introduced the calligra-phic flourish.

Sculptor Sankho Chaudhuri, whose centenary this year went more or less unmarked, had joined Kala Bhavana as a student in 1936. He describes in an essay in the Nandalal Bose Centenary Exhibition catalogue published in 1983 that Kala Bhavana became a beehive of buzzing activity when Nandalal brought the project to Santiniketan. Some 400 panels were to be painted. Prof. K.G. Subramanyan, also a Kala Bhavana alumnus, had written in the same catalogue that Nandalal had painted about 100 panels, all by himself.

Chaudhuri, who had been a part of this frenetic activity, describes how such a large number of panels were painted so quickly. The younger students prepared the paper and ground the pigments. Nandalal drew the quick outline with his brush and ink. His associates filled in the colour and the final touches were given by Nandalal.

Haripura hosted the 51st session of the Congress with great zest. There were 51 ornamental gates and welcome arches. A chariot drawn by 51 bullocks brought the party president, Subhash Chandra Bose, to the venue. Reports suggest that it was a mild session, but marked by two interesting facts. First, the ideological differences between Mahatma Gandhi and Bose came out in the open. Second, it revealed a rare glimpse of a Gandhian aesthetic vision, which if nurtured would have spelled a richer trajectory for Indian art. Instead of making art an elitist pursuit cloistered closely within the confines of fashionable homes, it would have a wider connect with the ordinary people making it an integral part of the social fabric.

From 1936, Gandhi became drawn to Nandalal's art and his ideals. He requested Nandalal to organise art exhibitions at the Lucknow and Faizpur sessions. Seeing the enthusiastic response to these art shows, Gandhi asked Nandalal to undertake the decoration of the Haripura Congress pavilion, and portray village scenes familiar to the ordinary people, using cheap local material.

Initially, Nandalal was hesitant, but then he accepted the challenge. He spent some months at Haripura studying the local people, their customs, their work and making endless sketches and studies. Says A. Ramachandran, who had been a student of Kala Bhavana, "From Gandhi's brief suggestions, Nandalal brought to the Haripura panels and to his art practice a whole philosophy of working with local materials and local traditions which could reach out to the community more effectively."

Needless to say, Nandalal accepted no remuneration to undertake this mammoth project, but ended up becoming a household name because of it.

Compared to the verve seen in the Haripura Posters, the illustrations that adorn the Constitution of India strike a more restrained note. The pages that mark the beginning of each part of the Constitution, carry drawings by Nandalal on the top. Most of the illustrations are monochromatic line drawings with only a few coloured exceptions. But Nandalal was a thinking artist and within that limited space that he gave himself, he captured the key emblems of 5,000 years of India's visual and civilisational history. With his strong drawing, he has depicted a Harappan seal, a Chola Nataraja, the Nalanda seal symbolising its monastic community, an illustration of Mahavira in the style of a Jain manuscript illustration.

In the drawing heading Part XIII, the artist has quoted from the famous bas-relief of Mahabalipuram showing Arjuna's penance. In the illustration heading Part V showing Buddha delivering a sermon, the artist has added a line at the bottom that seems to be a copy of a Brahmi stone inscription. These teasing illustrations are a treat.

The well-displayed and well-lit show has a couple of flaws. One is the absence of explanatory wall-texts. For a new generation of viewers, it is very important to understand the historical context as well as some highlights of the visual language. Second, a serious check of the captions is essential. For instance, a Jain warrior sounds like an oxymoron. Khanjuniwali (a player of small cymbals) is clearly a male figure. Many of the errors in labelling may have occurred when the collection entered NGMA more than three decades ago. But for all that, it remains a must-see exhibition.