It seemed like a good retirement plan. Congressman P.V. Narasimha Rao was done with his political career - or so he thought. So he closed his bank accounts and started getting rid of his personal belongings. He wanted to lead the life of a monk in the Mouna Swamy Mutt at Courtallam in Tamil Nadu.

And then, Rajiv Gandhi was killed in a bomb blast - and Rao changed his mind about retirement.

"In April, he was about to become a monk. Two months later, he was the Prime Minister of the biggest democracy in the world. You can't make this story up," says Vinay Sitapati, the author of Half Lion - How P.V. Narasimha Rao Transformed India (Penguin Random House India), which will be released tomorrow to mark 25 years of the liberalisation of the Indian economy.

Sitapati notes that within 24 hours of Gandhi's assassination, Rao was writing about his own strengths and weaknesses in his private diary. He mentioned that he lacked a mass base, had little charisma and had not been keeping well. But he also counted his strengths, and looked at the weaknesses of his opponents in Delhi. He plotted to take over the presidency of the Congress party with the aim of becoming the PM. And he did.

The book by Sitapati, who studied law at the National Law School, Bangalore, and Harvard University, is based on interviews and documents. He interviewed more than 100 people, including government officials, Rao's finance minister and later Prime Minister, Manmohan Singh, his cook and personal doctor. But his primary sources were Rao's own papers, including his private diaries.

"He thought very much in text. He kept notes of everything. He even kept notes on the day the Babri Masjid was demolished. The level of detail in his diaries and other papers is astonishing," Sitapati, 33, says.

Rao has been a bit of an enigma in Indian politics - revered as much as he has been abused. As PM, he was often accused of being indecisive, but lauded for ushering in economic reforms. He was a learned scholar who also believed in astrologers and godmen. He led a frugal life but could be corrupt for political survival. He relied on consensus, but was known to be vindictive. He was a family man with eight children (his wife, Satyamma, died in 1970), but had adulterous relations.

"No world leader was able to achieve so much with such little power. His colleagues hated him. He led a minority government. But he survived and showed that the Congress party could be run without the Nehru-Gandhi family," he says.

Sitapati, who is slated to complete his PhD in politics from Princeton University this year, says the book happened by chance. He had been asked to write a book on Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel, but was intrigued by the absence of literature on Rao.

"I am a child of the Nineties. Every major change around me was because of Narasimha Rao, but there was hardly anything about him in the form of books. All my friends in Mumbai knew the name of Mahesh Bhatt's second wife, but I don't think they knew anything about Rao," he says.

It took him exactly a year - from April 2015 to April 2016 - to complete the book. "I just got lucky with the papers that were given to me by Rao's family and that made it possible for me to approach people to get more information," he says. He believes his own academic background also helped him piece together Rao's political career. The book has around 1,100 footnotes.

"I have no political angle. I wanted to give him his due. His corruption, his romantic life, his contribution to India, I chronicle everything," he says.

The author believes that Rao, and not Manmohan Singh, was the father of liberalisation in India. But there was a reason why Rao wanted Singh to be in his government. "Liberalisation was politically unpopular, even within his party. But he knew how to handle it. In a typical CWC [Congress working committee] meeting which was rancorous, when Congressmen accused him of selling out to the IMF and World Bank, he would tell the members, 'Don't look at me, ask Doctor saab. He is the one telling me what is good for the economy,' he would say, pointing to Manmohan Singh. That was a straight lie. But he was able to do this again and again," Sitapati says.

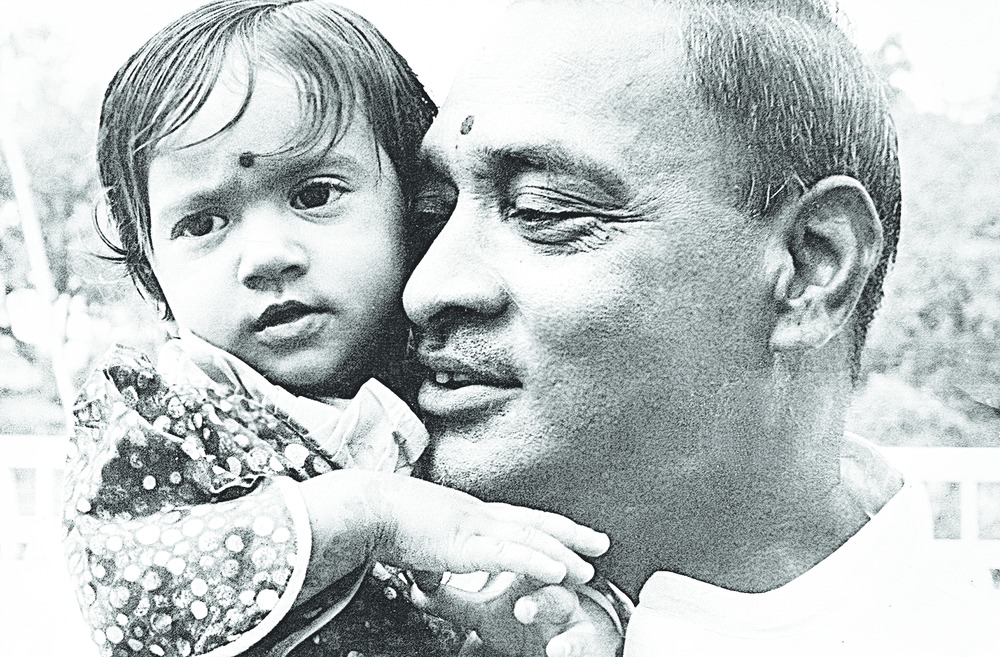

Pic: Rohan Mishra

He also started introducing almost every reform with a preamble on how Nehru, Indira and Rajiv Gandhi had envisioned such a change, making Congress more open to reforms.

Rao, Sitapati writes, tried to keep Sonia Gandhi happy without letting her influence his policies. He would meet her often and called her twice a week. "Sometimes Sonia's secretary would keep him waiting for 3-4 minutes (on the line). He told P.V.R.K. Prasad, his media advisor: 'I don't mind waiting, but the PM of India minds,"' Sitapati says. But at the same time Rao would manoeuvre and push Rajiv Gandhi's loyalists out of important party posts.

"He kept Intelligence Bureau reports on everybody, his friends, his enemies. For instance, if his main opponent in the party, Arjun Singh, bought four acres of land near Bhopal, he would know it the next day. Information for him was power," Sitapati says.

The book also looks at Rao's "love interests" - which the former PM himself wrote about in a semi-autobiographical novel The Insider, published in 1998.

His "romantic relationship" with Lakshmi Kantamma, a Lok Sabha MP from Andhra Pradesh, carried on from 1962 to around 1975, Sitapati writes.

"He was open about their relationship. Lakshmi was a Congress MP from the Telangana region. A rare woman in Andhra politics, she was ambitious and determined. She was also fiercely loyal to Rao," Sitapati notes. She later became a sadhavi, perhaps inspiring Rao to contemplate an ascetic life.

Besides liberalisation, Rao is also remembered for his role - or lack of it - during the demolition of the Babri Masjid on December 6, 1992. Sitapati, however, doesn't agree with his detractors who believe Rao did not move to stop the destruction.

"It is a straight lie that he didn't try his best to protect the mosque. It is also a lie that he was soft on Hindutva. After the Babri demolition, the Congress rallied around Rao, but his alleged complicity in the whole thing was resurrected after a few years. Sonia Gandhi's coterie hoped that by blaming Rao, they could kill two birds - bring Muslims into the Congress fold and regain the Nehru-Gandhi family legacy," Sitapati says.

Rao, he adds, held secret talks during the Ayodhya movement with an array of Hindutva people including Lal Krishna Advani of the Bharatiya Janata Party (BJP). "He was convinced that he was more Hindu than them. He would talk to them in Sanskrit," Sitapati says. He believed that he had struck "deals" with Advani and other BJP leaders such as Bhairon Singh Shekhawat and Atal Bihari Vajpayee and that nothing would happen to the masjid. He was clearly wrong."

The former PM never forgave Advani for the Babri demolition, he stresses. "He was so upset with Advani that he went out of his way to name him in the Hawala case that led to Advani's resignation as MP. But for the Hawala case, there was a chance that Advani would've become a PM later. Rao was a vengeful man when it came to dealing with his enemies," Sitapati says.

One man who chose to remain loyal to Rao was Manmohan Singh. "He has never said a negative thing about Rao. Singh's ability to be faithful to Rao's legacy without irritating Sonia shows that he learned something from Rao," Sitapati says.