|

I’ve been waiting to hear these words for 10 months. So when the phone rings, I can immediately identify the voice at the other end. “Can you come up in 10 minutes,” the dulcet tones ask.

Even though we lived in the same building, I’ve been finding it difficult to pin down Moushumi Chatterjee. I try to catch her whenever she comes down from Mumbai, but have no luck. Every time I call, I am told, “Madam to choley gechhen (Madam has left).”

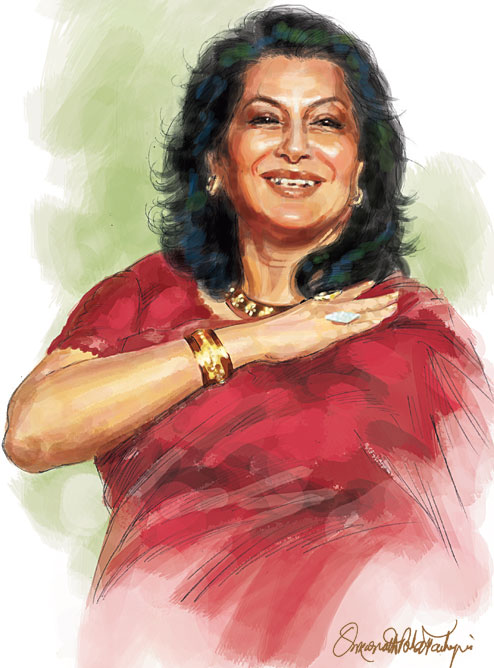

So when I am finally summoned, I am a bit nervy. But the moment she walks into her living room, smiling and caressing her tresses, I stop fidgeting.

It’s a smile that I’ve known for long. And it’s such a warm smile that it makes me forget I am addressing one of the most well known faces of Hindi cinema of the splendid Seventies. I see instead a woman dressed casually in a Tee and capris.

“I feel good,” she says. “I slept, ate and slept again,” she adds softly, revealing those signature crooked teeth. Ah, I say to myself — this is going to be a relaxed evening, after all.

And it certainly is. The moment I mention Aparna Sen’s new film Goynar Baksho — in which Chatterjee plays Rashmoni, an old widow’s ghost — she takes over. She’s ebullient, confident and articulate — so all that I have to do is sit back and enjoy the conversation.

But then, her confidence is not surprising. She has been in the limelight ever since she was in Class V, when director Tarun Majumdar cast her in and as Balika Badhu in 1967. Subsequently, of course, she has delivered many memorable films — including Parineeta (1969), Anuraag (1972), Benaam (1974), Roti, Kapada Aur Makaan (1974), Manzil (1979), Pyaasa Saawan (1981) and Angoor (1982).

“I was never the ambitious kind; I am basically a very lazy person. But I have been tremendously lucky. That is why I say God is not only kind but partial,” she laughs.

Indeed, wealth, recognition, and power came to her when she was in her early teens. When she was 14, she married Jayanta Mukherjee, the son of one of Bengal’s — and even Bollywood’s — most popular singers, Hemanta Mukherjee. “I did it because then I would not have to go to school,” she says.

Her own background, she adds, was conservative, and had little to do with cinema or music. Her father’s father was a judge, and her mother’s father a zamindar in what is now Bangladesh. She was the first woman in the family to start working.

Hemanta Mukherjee noticed her during the filming of Balika Badhu and asked her hand for his son. “After the film, every elderly man wanted me as his daughter-in-law and every young man saw the balika badhu as his wife! There were so many offers,” she says. Her family was not keen that she continue as an actress, but her father-in-law encouraged her to carry on.

Chatterjee has been acting, on an off, for over 45 years. Her role as the boori mashi (old aunt) in Aparna Sen’s The Japanese Wife (2010) prompted the director to cast her as Rashmoni. She was, however, not the first choice, but Chatterjee doesn’t think that matters. “Those approached earlier perhaps didn’t get the character right, thinking it was a silly old woman talking about love and sex.”

The story of Goynar Baksho, written by her uncle, Shirshendu Mukhopadhyay, is set in Faridpur in Bangladesh. And since that’s where Chatterjee’s origins lie, she quite enjoyed speaking in Bangal bhasha in the film. “I speak the tongue sometimes with my brother and sister,” she says proudly. “Of course, I do most of the bok-bok (chatter).”

So how is it working with Aparna Sen? “She wrote an excellent script. She is very passionate about her work and I have a lot of respect for her,” is the reply. Yes but what happens when two strong-willed artistes clash?

“Oh, that happened a few times. In one scene with Konkona, I had to say my lines but the camera wasn’t focused on me,” she says. “I thought the scene required that the focus be on me, but the director didn’t agree.”

And then? “I was upset. I left the sets and sat in my make-up van. Then Aparna came running to me. She listened to what I had to say and we sorted out the problem amicably.”

Her motto, quite clearly, is to speak her mind, and ask a question when there’s something she doesn’t understand. “It was the same with all these big guys such as Ajoy Kar, Tapan Sinha and Tarun Majumdar,” she says.

The talk progresses to the plight of widows in India, especially in the old days. Chatterjee recounts an encounter she had as a teenager with a distant relative, a widow. “She was wrapped in white and her hair was cropped short. She was married when she was seven and lost her husband to typhoid six months later. She was very good looking and I told her, ‘You look like a foreigner.’ She did not understand the meaning of the word.” But what followed shook her. “She showed me a scar on her back — because she had eaten a bit of non-vegetarian food from the kitchen, just out of curiosity. She was nine then.”

The actress is quiet for a while. The stillness breaks only when Dodo, her eight-year-old Labrador, saunters in after an evening walk. Dodo leaps on to the sofa, and, for that, has to be taken away.

“At one time, I had 11 dogs in my house, including street dogs,” she recounts with obvious pleasure. “I had named a black dog Beguni, because she was as thin as a slice of brinjal.”

As a child, she had once even brought home a cow. “I noticed that Lokkhi, our milkman’s cow, wasn’t being fed properly. So one morning, I took some gur and rotis for her, and she followed me as I led her to our house.”

Was shooting with a monkey in Ogo Bodhu Sundari (1981), Tollywood’s adaptation of My Fair Lady, as simple? “I had no problem having a monkey sit on my head. I got scratched on the nose once, but that was okay. What worried me was that the animal was pregnant,” she says. “I think human beings are beasts and must be feared, not animals.”

God, nature, animals, humanity — the words crop up often during the interview. But this life member of the International Society for Krishna Consciousness (Iskcon) clarifies that she is “not religious, but spiritual”. She is also confident that she’s going to be born again. “I just know; it’s a gut feeling.” Yes, I tell her, we want more of you. “Then you too will have to be born again,” she quips.

Chatterjee is still quite the chirpy actress we’ve known and admired. “I love to be childlike,” she smiles. “Why, a director had even said that I would forever be either 8 or 80, nothing in between!” She was everyone’s sweetheart, off screen as well. “Tarun kaku (Majumdar) called me his eldest daughter,” she says happily. And Uttam kaku was one of her fondest well-wishers.

But she was happiest as her father-in-law’s child. “He was my father and mother when I went to Bombay after my marriage,” she says. Indu (her actual name is Indira) is always right, he would say. Her extended family of in-laws, she adds, has also always supported her. Even when rumours were rife, linking her to many men, “they all stood by me”. Let them say what they want to, her father-in-law would tell her — “That’s a price you have to pay for being famous.” An aunt-in-law would laugh away the rumours and say, “Tor biye te nojor laagbey na (It will only protect your marriage from the evil eye.)”

She is equally proud of her husband (better known as Babu) and Moushumi uses two phrases to describe him — a gem of a person and a hardcore romantic. “He used to be a singing sensation in his college… He has many good-looking women friends, some of who remain unmarried till today,” she says, sounding rather pleased.

So which way is her energy headed now? “I don’t know, I may not work at all. I may turn producer or maybe go the spiritual way. But direction is certainly not my cup of tea.” What about politics? The actress had a brief stint in 2004 when the Congress fielded her from the Calcutta North East constituency against Trinamul’s Ajit Panja.

“People told me that I wouldn’t be able to defeat him — but I did. Of course, I soon realised that I was a scapegoat.” The winner turned out to be the CPI-M’s candidate. But Panja was apparently quite mad at her and told her, “Aapni ki bhebey esechhilen (How dare you come into this)?”

Our encounter’s come to an end. With one last look at a huge black-and-white photograph of her with her husband and their newborn elder daughter, I bid goodbye to her for the time being. But not without taking back with me the flavour of an evening well spent.