-

AGE-OLD BOND: A mural in the House of Commons shows Sir Thomas Roe, envoy of King James I of England, presenting his credentials at the court of Mughal Emperor Jahangir

In the summer of 1614, Patrick Copland, a chaplain in the East India Company, returned to England after spending two years in India. On the ship with Copland was a young Bengali boy who would create history. Copland had spent a year teaching him — chiefly by signs — 'to speake, to reade and write the English tongue and hand'. The nameless Bengali would be the first Indian to arrive on English soil, four hundred years ago.

Educated at the Aberdeen Grammar School and Marischal College, Copland believed in the power of education as a process of civilisation. When the East India Company established a trading post in Surat in Gujarat in 1612, Copland immediately joined the Company as a chaplain and left for India. Part of his mission would be to educate a native. To him, educating the young Bengali boy in both learning and Christianity was an evangelical duty; the boy, he thought would help him to convert his own people; the British he believed were 'civilising the natives'.

The arrival of the first Indian in 1614 caused a stir in London. As the young Bengali walked down the streets, he would be followed by children staring at him open-jawed; women would watch through tiny cracks in their doors. Even Shakespeare is believed to have alluded to this disposition of Englishmen to stare at an Indian. In his play The Tempest, the ship-wrecked Trinculo says on first seeing the dark-skinned native Caliban:

'What have we here? A man or a fish? Dead or alive? A fish!... Were I in England now, as once I was, and had but this fish painted, not a holiday fool there but would give a piece of silver. There would this monster make a man. Any strange beast there makes a man. When they will not give a doit to relieve a lame beggar, they will lay out ten to see a dead Indian.'

Copland's student proved remarkably clever at picking up both the English language and the Christian faith. After two years in England, Copland wrote to the Company that his pupil had increased his knowledge of Christianity, and suggested that he be publicly baptised 'as the first-fruits of India'. The Company consulted the Archbishop of Canterbury, George Abbot, who agreed to the proposal.

-

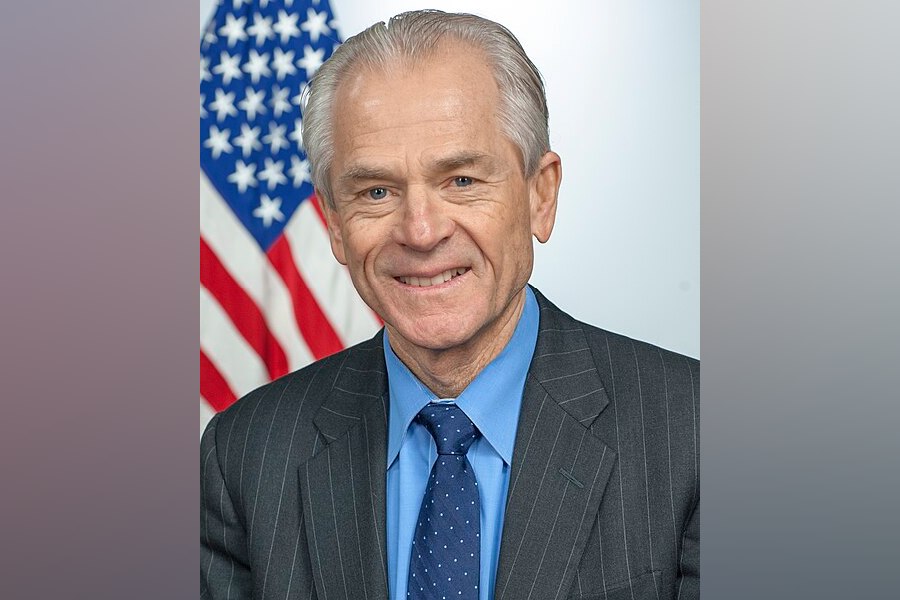

Sir Thomas Roe

On Sunday 22 December 1616, a boisterous crowd surged towards the Church of St Denis on Fenchurch Street. The week before Christmas was usually a busy one in this area, with people passing through doing their shopping, but the crowds that day were particularly excited. They had come following the announcement that a native lad of Bengal was to be initiated into the Church of Christ. The members of the Privy Council, the Lord Mayor and Aldermen, the shareholders of the East India Company and its sister company in Virginia, all waded through the 'sea of upturned faces' to reach the densely packed congregation. The rite was administered by Dr John Wood and the boy from Bengal was christened Petrus Papa or Peter Pope, a name chosen for his baptism by King James I himself.

Peter Pope remained a diligent pupil and was soon translating from Latin to English. He successfully translated from Latin the sermon delivered by his teacher in a church in Cheapside to the Honourable Virginia Company in 1622. The English translation was printed and sold at a shop in Cornhill near the Royal Exchange and duly credited: 'Peter Pope, an Indian youth, borne in the Bay of Bengala, who was first taught and converted by the said P.C. And after baptised by Master John Wood, Dr in Divinitie in a famous Assembly, before the Right Worshipfull, the East India Company at S. Denis in Fan-Church Streete in London, December 22, 1616.' The sermon was called 'Virginia's God be Thanked' and dealt with the success of the affairs in Virginia over the last year. It could be classified as the earliest work by an Indian to be published in England.

Copland had successfully imported and recognised the 'first-fruits of India'. Over the next four hundred years, many more would come, and the two nations would be tied together by history.

A strange coincidence took place in 1614. As Copland was escorting the young Bengali boy on to a ship bound for England, Sir Thomas Roe, Member of Parliament for Tamworth, was preparing to sail in the opposite direction: from England to India. He was to be the envoy of King James I to the court of the Mughal Emperor, Nur-ud-din Salim Jahangir. On 2 February 1615, Roe stepped on board the Lion at Tilbury docks with fifteen attendants. The voyage took six months, the Lion navigating round the Cape of Good Hope. On 14 September the ship dropped anchor off the port of Surat and an emissary was sent to prepare for the arrival of the new ambassador. Roe's brief was simple. He had to win over the Mughal Emperor and secure the trading post of Surat. He would be the first Englishman to be stationed in the Mughal court of Agra. On 25 September, the preparations were over. The Lion was decked with colourful streamers and flags and a 48-gun salute heralded the arrival of the ambassador. He was received in a splendid tent by the chief of Surat. The port city at that time was ruled nominally by Prince Khurram, son of Jahangir, who had given the powers to the local chief Zulfikar Khan and Mukarab Khan. They preferred the Portuguese to the English, so Roe would have to cut his diplomatic teeth in some tricky waters.

Wasting no time, he journeyed north bearing the gifts for the Mughal Emperor that had been sent by King James I. He finally had the audience with Jahangir in Ajmer on 10 January 1616 and requested a treaty that would give the East India Company the rights to reside and build factories in Surat and other areas. In return, the Company would provide the Emperor with goods and rarities from the European market. Jahangir, impressed with the British fleet's defeat of the Portuguese, immediately granted permission. Roe looked like the sort of person Jahangir could do business with. Besides, the Emperor calculated that it would be useful to have the British play off the Portuguese who had been fanatic in their religious outlook. Roe remained as envoy from 1615-1619 and greatly enjoyed his time at the Mughal court, frequently dining and drinking with the Emperor who he described in his journals as 'very merrie and joyfull'. In 1618 the first British factory was started in Surat. Many more would follow over the next two centuries. The beginning of the England's relationship with India would sow the seeds for four hundred Indian summers in Britain.