There is no such thing as an appointment with Bimal Gurung. You catch the Gorkha Janmukti Morcha (GJM) leader - and czar of Darjeeling - where you can, and if he agrees, speak to him. No formal interview, mind you.

So, here I am, sitting on the dais with him inside a school for poor Gorkha children at Malidhura on the outskirts of Darjeeling. I am waiting for him to end a meeting with dozens of teachers from hill schools who have filled up the cavernous school hall.

Sensing my impatience, Gurung stops the meeting halfway, only to have a stream of young men and women in the audience sidling up to the dais. They touch his feet, he blesses them.

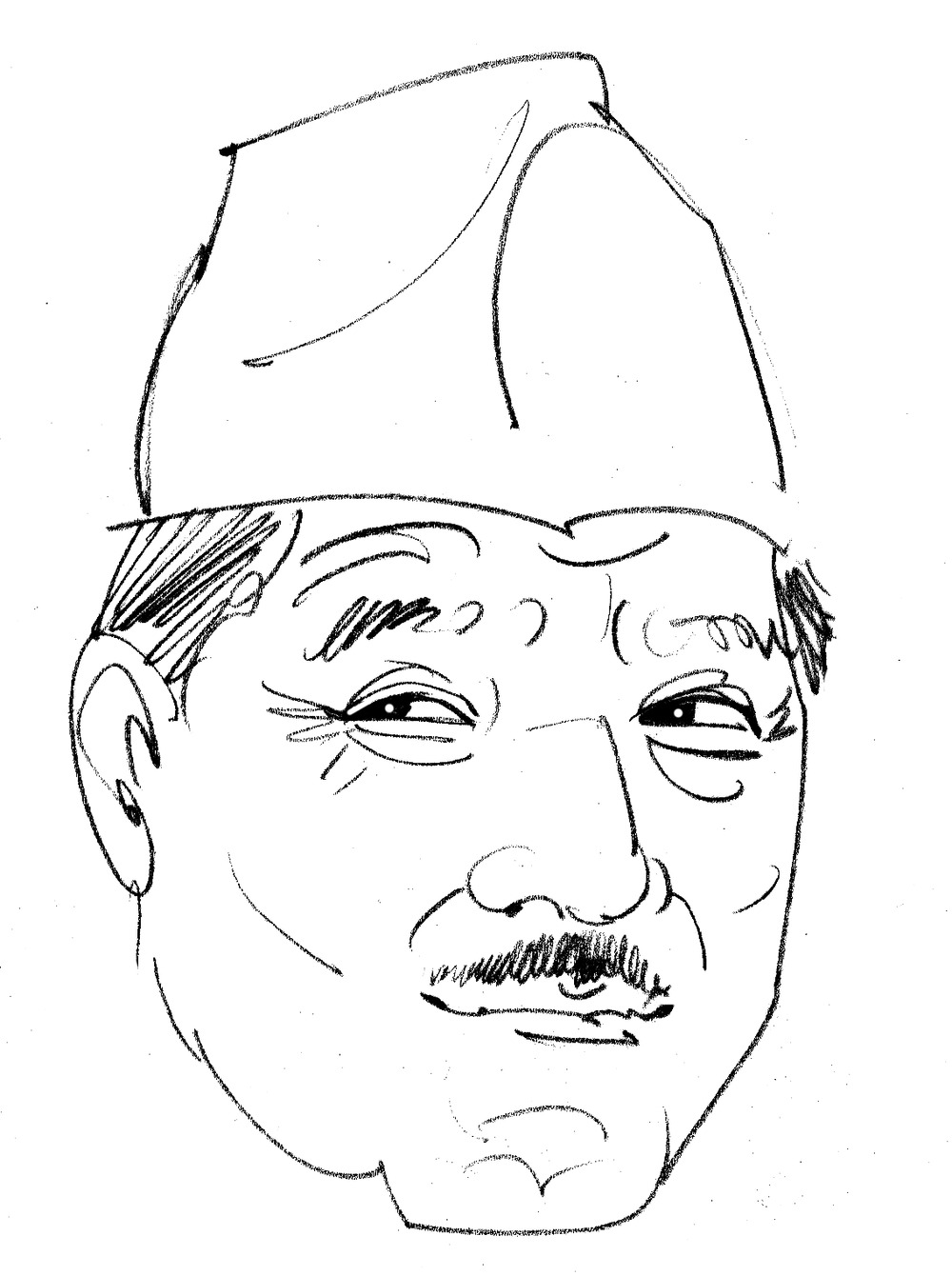

The 52-year-old leader looks quite the genial patriarch. It is difficult to believe this is the same person who has just ignited the hills with his call to resume an all-out agitation for Gorkhaland, a separate state for Gorkhas, encompassing the hills and much of the foothills of Darjeeling.

"Gorkhaland has to happen and will happen. We are determined to achieve this,'' says the GJM boss; he discloses bits of a strategy that includes a four-day dharna in Delhi.

No matter how much Gurung - lean and athletic with a cascading delivery style reminiscent of a waterfall - stresses the movement will shun violence and follow the non-violent path shown by Mahatma Gandhi, Darjeeling appears to be on edge.

Darjeeling has been living out a rare bout of peace in the last four years. Gurung, a confidant-turned-foe of Subhash Ghisingh, the late Gorkha National Liberation Front leader and proponent of Gorkhaland, had cast aside his demand for a separate state carved out of Bengal. He had settled for the Gorkha Territorial Administration (GTA), a development board born of an accord with the Bengal government just as Ghisingh had once done. GTA is an autonomous body set up in 2012 to help develop the three hill subdivisions of Darjeeling, Kurseong and Kalimpong.

That's all in the past now.

This year, Gurung has already called for the hill schools - Darjeeling is home to some of the finest boarding schools in the country - to wrap up early and send the students home on an extended winter break in preparation for the agitation.

He says he is already trudging through hill towns, often literally, holding meetings. But with his party being a BJP ally - the BJP won from Darjeeling in 2009 and 2014, thanks only to him - he clearly expects to achieve something from his Delhi sit-in, especially at a time when relations between Bengal chief minister Mamata Banerjee and Prime Minister Narendra Modi have reached a nadir over demonetisation.

"We will hold a massive rally in the Terai region to press for our demand,'' he says, adding that the agitation, if non-violent, will be protracted.

But what has prompted him to resu-me the agitation after shaking hands with Mamata Banerjee whom he once likened to a mother?

Gurung claims that though the chief minister created the GTA, she is "now starving us of funds". He also accuses the state government of going back on its word and not transferring to the GTA several of the departments, including the crucial public works department (PWD), land and land reforms.

"They keep meddling in GTA affairs, making it impossible for us to work or deliver," the GTA chief executive fumes. "Let Mamata Banerjee rule Bengal but we should be allowed to govern Darjeeling. What have Bengal governments done for Darjeeling? Whatever we have was created by the British."

Clearly, the falling-out between Gurung and Banerjee, much like their bonhomie, has been no less than spectacular. Hill watchers attribute it to the chief minister's move to form and fund several GTA-like boards for different hill communities (Lepchas, Sherpas, Tamangs), weakening Gurung's political base while expanding Trinamul's own.

In the course of our hour-long conversation, Gurung makes repeated references to Banerjee's "divide and rule policy" in the hills. But it won't pay, he says.

"Prime Minister Modi had tried his best to grab Bihar from Nitish Kumar. He had announced so much money for Bihar. But what happened in the end? Who did people vote for?" he asks, his eyes narrowing and a smile flickering across his face. "They (new boards) will take all the funds and then they will vote for me."

He makes sure you get what he is driving at. He talks about the three hill seats he won in the Assembly elections earlier this year; the same, where the ruling party drew a blank. "I won all 45 GTA seats (many of them uncontested) in 2012 and will win again when the GTA elections happen (next year) even if they hold it tomorrow," he says, as if daring his detractors' claims that he is a spent force in hill politics.

But a shadow hovers over Gurung. The CBI has implicated him and a host of GJM leaders in the 2010 murder of All India Gorkha League president Madan Tamang.

"It's a conspiracy. I was in Kalimpong the day he was murdered in Darjeeling."

With the Calcutta High Court restricting his movement to the jurisdiction of the city metropolitan court while granting him anticipatory bail, Gurung will find it difficult to return to Darjeeling for any agitation.

He, however, says he will accept whatever the court decides even if that means going to jail. "I am not afraid of anything. I am ready to die if that helps or serves my people," he promises with a flourish.

With donations and funds from the Members of Parliament Local Area Development Scheme (MPLADS), Gurung has set up the CBSE-affiliated Kanchanjunga Public School. Here, 700 children from the hills, Dooars and Terai, study without having to pay fees.

"My mother had asked me to do something for the education of poor children because they could not put me through school. I kept my word," he says. His own daughter has graduated from a Bangalore law school and is now a Calcutta High Court lawyer.

Gurung might not have got a chance to study beyond Class V, but today, he stops by at the Kanchanjunga school almost every day at the crack of dawn - for a game of badminton with some friends. "I have to stay fit to fight for Gorkhaland," he says.

Anything to stay in the game.

tetevitae

1964: Gurung is born into a family of tea garden workers. Does odd jobs in adolescent years to support family

1986: Subhash Ghisingh's Gorkha National Liberation Front (GNLF) launches armed struggle, Gurung joins its youth wing

Loses older brother to the agitation

1988: When Ghisingh signs an agreement for the creation of the semi-autonomous Darjeeling Gorkha Hill Council, a disillusioned Gurung leaves the organisation

Goes underground and eventually resurfaces in 1991. The 1990s are spent fighting charges of murder and illegal possession of firearms

1999: Re-joins GNLF. Parts ways again in 2007 when Ghisingh agrees to the implementation of the Sixth Schedule that signals an end to the separate state claim

Gurung now throws his lot behind Prashant Tamang, a Gorkhali from Darjeeling participating in Indian Idol. Tamang wins and riding on the sentiment, Gurung forms Gorkha Janmukti Morcha. Believes in the occult and claims the party name came to him in a dream