From several mosques and shrines in Kashmir you may often hear song wafting, like breeze rustling chimes. Durood, they call it, devotional tracts set to traditional tunes and collectively hummed. It’s a practice disapproved by conservative Islam, but it’s a social and spiritual custom Kashmiris have not entirely forsaken.

Should you lend a closer, keener ear, you’d sometimes discover that what you assumed to be crooning is actually someone crying. They come in ones and twos, and often in bigger groups, pick a corner or hug a post, and ceaselessly cry and murmur prayer. You may occasionally be stabbed by a wail, a dam-burst of desperation.

Above the daily humdrum of Kashmir there still floats a pensive, unassuaged air so insistent it makes prayer sound like a dirge. By twilight, it has risen from the houses of God and become a sullen shroud that defies cameras as well as it defies banishment. Nobody will forget their dead, nobody will cease waiting for the vanished. What’s the count? But don’t even get there, the numbers are too high and it’s not the numbers, it’s people. Parents, children, siblings, spouses, buried, or worse, missing without trace. Crying resumes each evening beneath the portals of mosques and shrines and rises to the skies like a shroud in flight. No place has cried so uninterrupted as Kashmir, it has cried so long crying has become its song. It often echoes with that stirring line from Vishal Bhardwaj’s Haider, itself a classic bibliography of Kashmir’s contending horrors: “Hamara aasmaan kaale parindon se ghira hua hai… Our skies are besieged by ravens…”

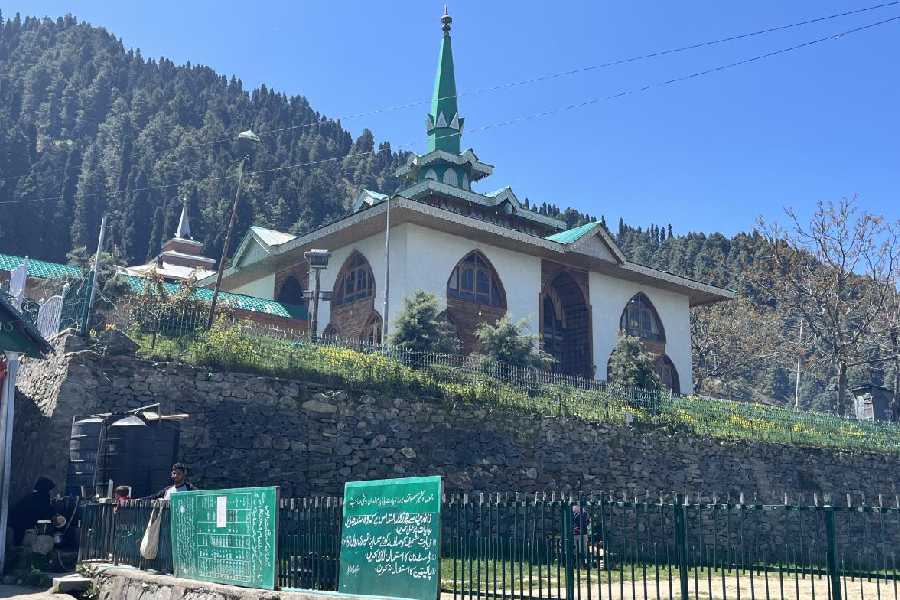

The ziyarat (shrine) of Baba Reshi curtained away by the lofty pines above Tangmarg in north Kashmir, is one such precinct sufferers come for solace. Here rests under an ornate canopy the remains of the revered Sufi saint, Payamuddin Sheikh, provider of benevolent shelter and solace. Here arrive, in unceasing droves, quite indifferent to the sporadic tableaux of electioneering, seeking benediction.

The Baramulla Lok Sabha contest has turned keener than most though. In the fray: a former chief minister (Omar Abdullah), a former separatist (Sajad Lone) and a forever rebel (Engineer Rashid), who has come from behind to spice up the campaign in a fashion reminiscent of George Fernandes’ fabled Muzaffarpur dare from jail in 1977. Engineer Rashid, a former MLA, is also behind bars, lodged in Tihar for the last five years on terror funding charges. His son Abrar is leading the “jail ka badla vote se lenge” charge with energy that has riveted the attention of both the Omar and Sajad camps.

But even in a vale so tiny — it is 130-odd kilometres long and 40km at its widest — it is possible to reach locations untouched and unbothered with the clamour of elections.

The tourism industry doesn’t mark out routes to them, the guides will never take you there, the state stays mostly away and averse, the politicians, oh but they barely even remember. Barely even at the time they require this realm most, at election time.

“Hamara siyasat se matlab nahin, siyasat ka hamse nahin (we have nothing to do with politics, politics have nothing to do with us),” so saying, Basheer Khan, cloth merchant in the one-lane bazaar of Kamblinar, wished us on.

Basheer’s aversion to the vote is just that: aversion. Quite simply about not giving anything to politics because it gives nothing to you. “I will not acquire a bigger shop or a plot of land or a better school for my children if I go and vote,” Alam said sardonically. “I have a chance of doing that if I run my shop well. We are happy being what we are, let me not be told some masiha (messiah) will change things overnight.”

His friends from Kamblinar’s little merchant community — half-a-dozen shopfronts, including a bread-and-tea vend — said they wanted to add no more to what Basheer had said.

We had arrived in Kamblinar quite by accident. We had climbed up the arrow road from Srinagar to the Tangmarg shrine, rounded the hill and humped over Gulmarg — teeming with the summer’s first tourists scratching about the dregs of remnant snow — and plunged down the back of the forests.

Quite suddenly, the clamour of tourist Kashmir had faded and an ante-dated Kashmir had taken over. We had travelled no more than 10 minutes downhill and we had plunged in time, into a radically removed environ from the luminous signposting of Gulmarg, shorn of its glitter, bereft of the excited hubbub of its hotels and eateries, the tinkle of easy cash and the chirp of commerce.

There was barely a dwelling to be seen that wasn’t ramshackle, barely a field that wasn’t being worked with bare human hands. We passed struggling horse carts and farmers pushing wheelbarrows. We barely came across motorised transport. We saw no hospitals or health centres, only the odd school where the classrooms were empty. There were no security people either, as they are elsewhere in the Valley.

The air was scented with the voluptuous foliage of spring, and doves darted about, beating the silence with their wings. The road had vanished and rubble had taken over. From somewhere, needling the azure sky, rose a muezzin’s call to prayer.

Baramulla votes on May 20