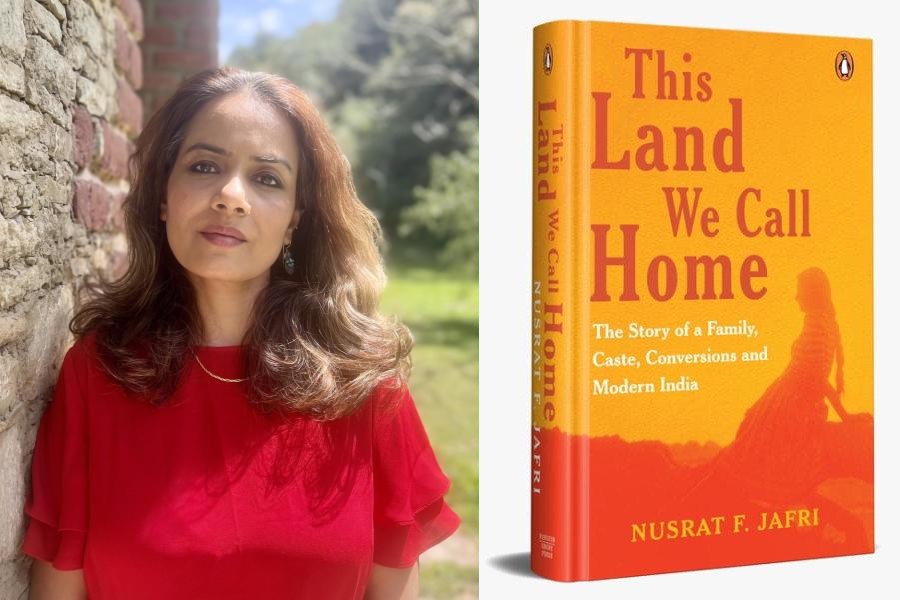

Writing has always been a source of joy for Nusrat F. Jafri, a cinematographer known for projects like Pilibhit, Chacha Vidhayak Hain Humare and Shahid. Inspired by her mentor and author Aanchal Malhotra, Jafri, who has dabbled in print journalism, maintained a blog, and explored screenwriting in the past, has penned her debut book This Land We Call Home. “While cinematography was my primary focus for some time, writing has always been a source of joy for me. I vividly remember during our initial online meeting for the South Asia Speaks mentorship programme, my mentor Aanchal Malhotra, an author, encouraged my writing skills, emphasising the importance of trusting the research and creative process. This affirmation helped dispel any lingering doubts I may have had.” A tete-a-tete with Jafri on her memoir that delves into her family tree, how the concept of conversion has changed and more.

For how long was This Land We Call Home in your head?

For as long as I can recall, I’ve always wanted to chronicle the history of my maternal family. The realisation that they belonged to the Bhantu tribe and that conversion to Christianity had substantially altered their lives always presented itself as an urgent topic worth exploring. The ongoing assaults on Christian missionaries and the skepticism surrounding conversions intensified my curiosity about the evolving implications of the term “conversion”. It has now become a highly charged word in the political discourse, carrying numerous negative connotations. Finally, of course, after I made it into the first cohort of the South Asia Speaks yearlong mentorship, it took me a little over three years to finish work on the manuscript.

You have traced your family lineage from your great grandparents Hardyal and Kalyani Singh and go back to the 1870s. The research must have been daunting as there’s very little archival material on the Bhantu tribe.

Indeed, it was quite intimidating, to say the least. However, I was fortunate to encounter wonderful individuals who directed me towards the appropriate contacts and resources. Discovering my great grandfather Reverend Hardayal Singh’s name in the meticulously maintained diaries of the Methodist Episcopal Church’s yearly meetings/conferences way back from the 1930s was a significant moment for me. It felt surreal now he existed in the real world and beyond just the anecdotes I had grown up hearing of him. The research process was the most enjoyable aspect of writing this book. I took great care to include details about the evolving cityscapes, changing perspectives, and architectural marvels of significant landmarks, particularly in cities like Delhi, Bareilly and Lucknow.

Were you looking for any answers while writing this memoir or did it have a therapeutic effect on you?

I wasn’t seeking personal answers, but I found writing in general to be therapeutic. Early in my research, when I realised the scarcity of material on the Bhantu tribe, I felt an even greater urgency to tell their story. It dawned on me that I was documenting an oral history of a tribe from an era that would be challenging to document, especially considering that those born before Independence were now in their 90s. I endeavoured to approach this narrative with utmost care and responsibility.

You touch upon the themes of caste, religion, migration, and conversion through your memoir. These elements still exist. Your thoughts....

The elements of casteism and religion permeate Indian society extensively perhaps just the same as they did a century ago. Conversion, on the other hand, has acquired a different meaning. It is viewed as a social taboo. Perhaps, one of the most intriguing aspects of our country is how the concept of conversion has acquired a new, highly charged identity. The act of adult men and women choosing to embrace another religion was much more mundane and commonplace than we care to acknowledge. For instance, my mother’s maternal grandfather belonged to the Bhantu tribe and converted to Christianity, while her paternal grandfather, who was a Kannauji Brahmin, also chose to embrace Christianity. Their motivations differed, but both made the decision to convert. It’s worth highlighting that many conversions to Christianity, particularly in Maharashtra, were often observed among the upper castes. This observation spells out the complexity of religious dynamics in India, where individuals from different social strata may be drawn to Christianity for a variety of reasons, including spiritual beliefs, socio-political factors, or personal experiences.

If every community strictly adhered to endogamy, society would have missed out on the multicultural richness that India now proudly displays. Endogamy, as much as it preserves cultures, can also create barriers between communities and limit interactions across diverse backgrounds. I take pride in being part of a multicultural and cosmopolitan family that embraces diversity.

You are primarily a cinematographer and know the art of storytelling. Do you think this story needed to be documented in written form and if this was the right time?

Indeed, there has never been a more opportune moment than the present. History books are undergoing revision, reflecting evolving perspectives. Even in politics what were once considered villains yesterday are now celebrated as heroes. The generation of Bhantus who witnessed the pre-Independence era and the denotification of criminal tribes are now in their nineties. Their oral histories and lived experiences are invaluable resources that we must prioritise. The present-day Bhantu world with respect to social and economic standing only reflects a shameful stagnancy.

Being a cinematographer may or may not have directly influenced my writing process, but it’s possible that it has contributed to a more visually descriptive style of writing. However, the medium isn’t as crucial as the urgency to share the story. I’m thankful that our book is now published, and if there’s interest in adapting it into a film, it will undoubtedly reach a broader audience.

As a cinematographer do you see the potential of the book getting translated into the visual form?

Certainly! I envision This Land We Call Home having great potential for adaptation into visual media. Historically, depictions of Bhantus and other so-called “criminal tribes” have often been portrayed through an Orientalist lens. However, I believe contemporary filmmakers have the capability to authentically portray the story of India’s original inhabitants who resisted colonial rule and persevered despite oppression. This is a story of honesty and resilience that demands to be retold on screen. Further, nestled within this backdrop lies the love story of another interfaith couple navigating their journey for self-identity and a quest for a place to belong paralleling the nation’s own journey to maturity.

Pictures: Penguin Random House India