Granted, “barrister” is a euphemism for politicians of a certain intellectual pedigree. But it is no myth that Indian politics was at one point quite literally the preserve of men and women of law.

Take a look at the first Cabinet of independent India. Jawaharlal Nehru studied law and enrolled as an advocate at Allahabad High Court; before that, he had graduated with honours in natural science. Sardar Vallabhbhai Patel didn’t complete his matriculation till he was 22, but he went on to study law and became a barrister. C. Rajagopalachari did his bachelor’s and then studied law at Presidency College in Madras. Kailash Nath Katju did his doctorate in law. B.R. Ambedkar studied economics at Columbia in the US and the London School of Economics in the UK, and also trained in law at Gray’s Inn in London. Syama Prasad Mookerjee did his master’s in Bengali and then went on to study law. Health minister for the longest time Amrit Kaur went to college at Oxford and was awarded an honorary Doctor of Laws degree by Princeton University, US, and so on and so forth.

In a paper published in Social Scientist in 1972, Prakash Karat wrote, “All Cabinet members [up to 1967] were divided into the two broad categories of professionals and politicians. The professionals are those recruited into the Cabinet for their ability and skill in some specific professional sphere of activity like law, economics, education, etc.” And you may nitpick at many of their isms today, but the role of these professionals in shaping the newly-birthed nation and its policies cannot be discounted.

“It was the intellectual elite — Brahminic, urban- centred and pro-British — who made current the idea of an Indian polity; India as a political community was, in one sense, their discovery. Thus it is not surprising that intellectuals remained the main actors in Indian politics,” writes Ashis Nandy in his 1973 paper The Making and Unmaking of Political Cultures in India.

However, as soon as participatory politics evolved in India — that is, politics became for and of the masses — the culture of Indian politics became aggressively anti-

intellectual, Nandy notes.

“Educational qualifications mean nothing. Siddhartha Shankar Roy was a very educated man but he was one of the worst chief ministers. Think of all the atrocities committed against Naxals during his time,” says Uma Chakraverti, feminist, historian and documentary maker. But this is not about good politicians and bad politicians, this is about “educated statecraft”.

Ray’s successor Jyoti Basu was a barrister from London’s Middle Temple, but he will be remembered more for the land reforms he initiated. He had a head for numbers and it is said he would sometimes correct figures spoken off the cuff by state finance minister Ashim Dasgupta, an economist with a doctoral degree from MIT in the US. Basu’s predecessor and Ray’s too was B.C. Roy, the first chief minister of the state — a doctor by training — credited with the making of modern Bengal. He built roads, satellite towns and townships, educational institutions. E.M.S. Namboodiripad became chief minister of Kerala a little after B.C. Roy’s time. He pioneered radical land and educational reforms in his home state. Fast forward some more years and Biju Patnaik was building schools and colleges, ports and power plants across Odisha.

The rise of the populist politician began in the 1980s. There was MGR in Tamil Nadu who pioneered the noon meal scheme for schoolchildren. NTR in Andhra Pradesh who made his politics about the identity of the Telugu people, just as Bal Thackeray made his about the Marathi manoos. Then came Jayalalithaa, Lalu Prasad, Mayawati…

Jayalalithaa reportedly topped the state in Class X but was a college dropout. Most of the others, however, were graduates or more. The current Lok Sabha has almost 400 graduate members.

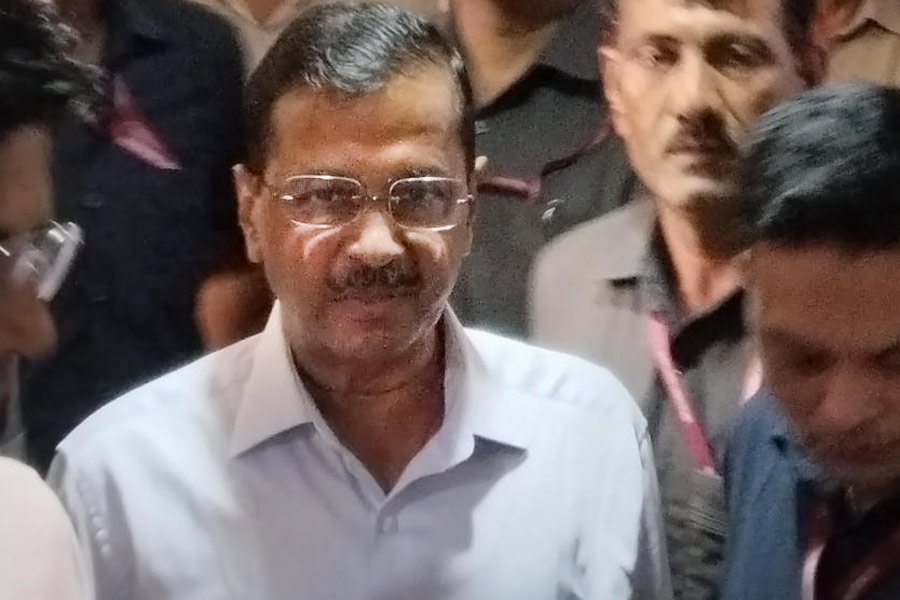

But the new breed of politicians are populist, more preoccupied with appeasing individual votebanks. Over the years, their brand of populism flourished. From schemes to benefit people in general, they moved to appeasing communities based on caste, gender, religion till, in 2019, Narendra Modi promised to transfer Rs 15 lakh to individual bank accounts if the BJP came to power.

Nandy’s “anti-intellectual politician” had arrived.

Intermittently, politicians did and still try to find intellectuals a place. When the erudite Narasimha Rao chose Manmohan Singh as his finance minister, he was looking for an able technocrat. The story goes that Singh, who was those days boss of the University Grants Commission, got a call asking him to report to the swearing-in ceremony; but when Sonia Gandhi anointed him Prime Minister, she was looking to offset her own political savvy as well as ambition with his intellectual aura. In 2007, Shashi Tharoor quit his career at the United Nations. In 2009, he joined the Congress but later said he had been approached by the Communists and the BJP too. Which goes to say that even 15 years ago, an intellectual politician was someone to be wooed, albeit discreetly.

How will you find educated people in politics? These days good students don’t participate in student politics, so where is the educated politician going to come from,” says Abhra Ghosh, who is a Calcutta- based retired professor of political science.

Sayantan Basu of the West Bengal BJP doesn’t disagree. “The participation of students in politics has decreased to a great extent. Forget participating, even college elections get barely a lukewarm response,” he says. Basu recently attended a conference in Delhi that marked 75 years of the ABVP’s formation and found the declining participation of students in politics a hot topic of discussion. “It is true across the country but it is especially true in West Bengal, which has typically witnessed a lot of political activity in its colleges,” says Basu.

Left-leaning actor Badsha Maitra, however, disagrees with this. “The Left Front has no seats in either Parliament or the Assembly, but brilliant students are still joining in flocks,” he points out.

Perhaps, but as many people in active politics point out, most of these “brilliant students” come from families with a history of participation in Leftist politics.

No sooner than Kangana Ranaut’s candidature from Mandi was announced, a slugfest broke out. Says Sabir Ahmed of Pratichi Trust, “These days, instead of being well-spoken, you need to be badly spoken if you want to succeed in politics — you have to be able to say hateful things, inciting things. An educated person will not

be comfortable with that. Which is why you will see educated people retract after joining politics or stay on but never fit in.”

And so, we continue to lose the “good” politician to manners, principles and career.

Former CPI(M) MLA Tanmoy Bhattacharya is more hopeful of the future. He says, “My personal belief is that we have already crossed the time of crisis. Now, in different countries across the world, educated, dignified, cultured people are again involving themselves in political work.”